Jaime Cummings and Ken Wise (NYS IPM), Jeff Miller, Mike Hunter and Paul Cerosaletti (CCE)

We are receiving reports and more questions than usual on pokeweed incidence this season from various parts of the state. Particularly with regards to it seemingly surviving glyphosate applications in fields. Some of us are familiar with this large weed, and know that once established in your fields, it can be a serious challenge to eradicate. And, sometimes by the time you notice it, it has already flowered and set fruit, and the birds are helping to spread it further.

Here are some quick questions and answers on pokeweed:

Why is pokeweed so challenging to manage? It’s a perennial with a very large and persistent taproot, and is also a prolific seed producer with a wide emergence period.

Why is pokeweed becoming more prevalent? Plowing and soil-applied residual herbicides were the typical management strategies for this weed. With the widespread adoption of no-till or conservation tillage practices, and a move away from some of those residual herbicides in combination with less crop rotation diversity, we are experiencing a resurgence of pokeweed.

Why do I still have pokeweed in my fields that were treated with glyphosate? Pokeweed seedlings can emerge from May – August, which means that you may have missed some of the later emerging seedlings during your typical early-season corn and soybean herbicide applications, especially if you didn’t include a residual herbicide in the mix. And, since pokeweed is a perennial, you may be trying to kill plants that over-wintered and have established huge and hardy taproots. It’s challenging to kill any weed with well-established taproots with a single herbicide application.

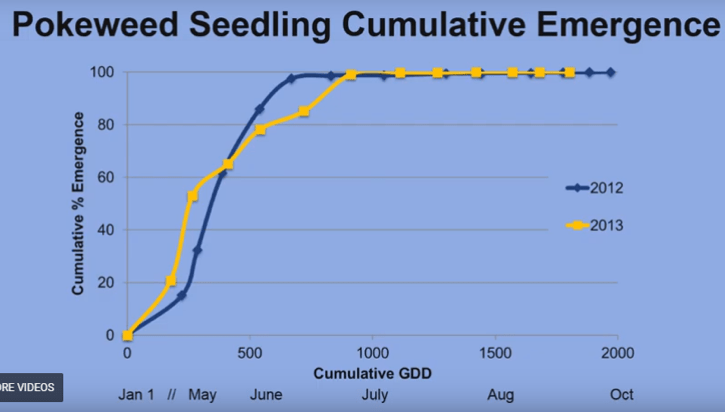

Pokeweed seedlings can emerge continuously throughout the summer, with a peak in May and ending in August (Fig. 1). This long period of emergence makes it difficult to manage with a single-pass program of post-emergence herbicides alone. And, it’s important to manage any seedlings that emerge later in the season, because although they are unlikely to set seed that season, they can produce a serious taproot to overwinter and pop up the following year (Fig. 2). Research by K. Patches at Penn State University from 2011-2013 investigated the biology and management of pokeweed, and determined that many herbicides (including glyphosate and plant growth regulators) provided at least 80% control, when applied with either air induction or flat fan nozzles (Figs. 3 & 4). And, in those trials, glyphosate applications after mid-June provided better control than applications made earlier in the season (Fig. 5). This is because systemic herbicides applied at flowering on perennials are more likely to be translocated down to the roots to kill the taproot. For increased later season pokeweed control, consider rotating into a small grain crop and applying herbicides in August to kill the seedlings that emerged after your typical soybean or corn herbicide applications.