The newest post in the blog series for the art history of New York City course, On/Off the Grid: Art and Cultures of Modern NYC, is being taught by Dr. Meredith Mowder. Jason Albuquerque, B.F.A. ’23, recalls his class’ outing to Christopher Park and the LGBT Center in the West Village. Jason discusses queer art after the Stonewall uprising and the impact of AIDS on LGBT+ community.

Not everyone can say their class started in front of a gay bar. On June 28, 1969, one of the most important uprisings of LGBTQ+ history happened here, at the Stonewall Inn. Located at 53 Christopher Street in Greenwich Village, the Stonewall Inn was a private club owned by the mafia. Back then, homosexuality was still considered sodomy and illegal in most of the U.S. Gay bars were a place of refuge for the LGBT+ community.

On that Saturday night, the NYPD raided the Stonewall. Female officers escorted cross-dressed individuals to the restroom to verify their sex. After several arrests, a crowd of over 200 people gathered outside the establishment. They became increasingly agitated. People threw pennies, bottles, cobblestones, and even set the bar on fire with the officers inside. A woman got hit on the head with a billy club while being arrested. “Do something!!!” Her words forever changed the course of history.

For the decades to come, multiple generations of queer artists have done just that: take action.

We discussed the work of Felix Gonzalez-Torres. One of his installations occupied a billboard on the corner of Christopher Street and Seventh Avenue. Two lines of white text read: “People With AIDS Coalition 1985 Police Harassment 1969 Oscar Wilde 1895 Supreme Court 1986 Harvey Milk 1977 March on Washington 1987 Stonewall Rebellion 1969.” Not all triumphant; these are important dates in LGBT+ history. But why aren’t they in order?

In contrast with the noisy streets of NY, “Untitled” (1989) had a certain poetic quietness. It forced the viewer to stop and think. I catch myself questioning how I perceive history. Perhaps history isn’t really linear. All we have to do is look at the news to realize that for every step forward, there are often a few steps back. The work of Felix Gonzalez-Torres speaks directly to the queer struggle to reach social gains.

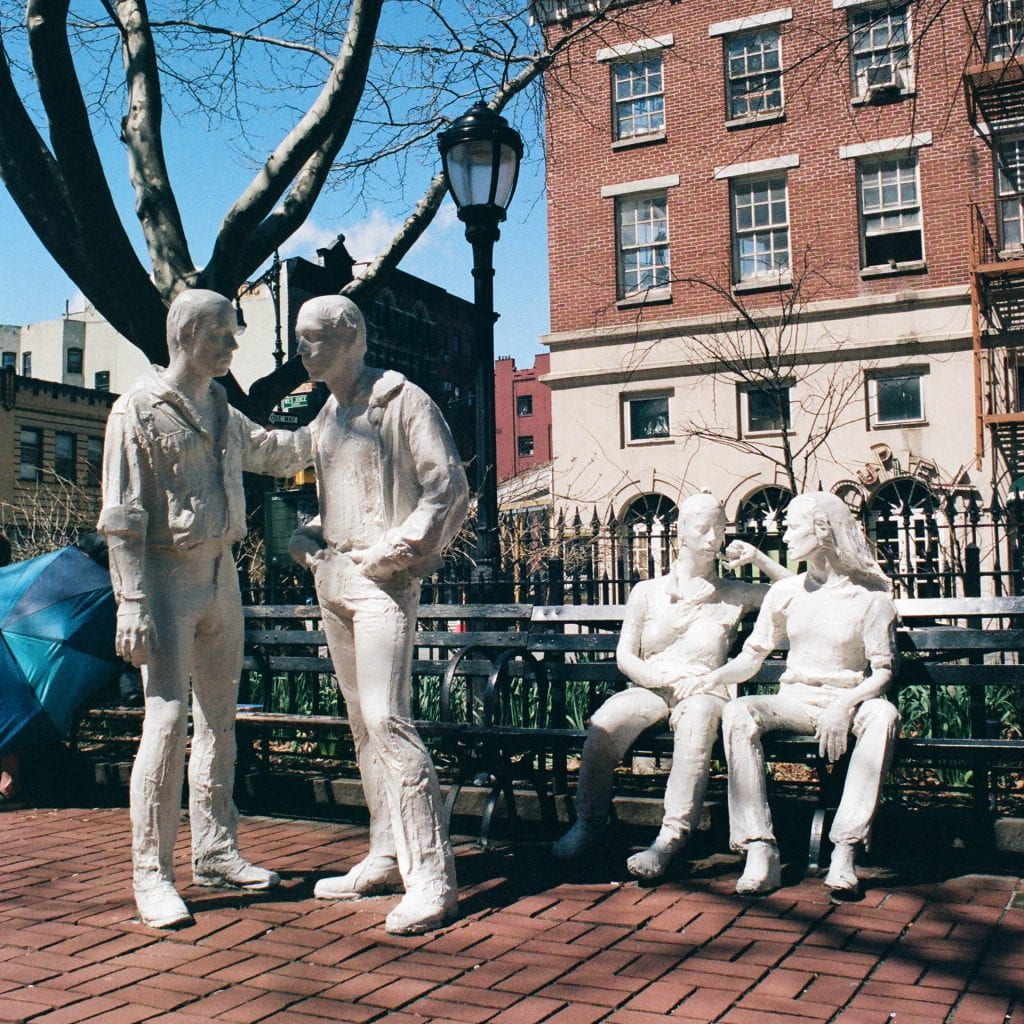

Next to us was another piece that also marked the anniversary of the Stonewall Uprising. George Segal’s Gay Liberation is all about gestures. Their interactions are subtle. Hands briefly touching or leaning on a shoulder. These people know each other. They are friends, maybe lovers. Yet, they are distant. We discussed how this sculpture also encapsulates the struggle of being queer in a heteronormative society: the figures are at once completely ordinary and yet also totally strange. These ghostly white figures are more than a monument to the Stonewall uprising. They are a reminder of those who are no longer with us due to the impact of AIDS and HIV.

I remember getting somewhat emotional when we talked about the work of Nan Goldin. For years, The Ballad of Sexual Dependency has been one of my favorite photobooks. I have always admired Nan Goldin. Her work explored the intricacies of love–the good and the bad. She believes that photography captures the truth. Not a beer was to be moved, not a smile to be forced. The Ballad was a diary she allowed us to read. Published in 1985, Nan prefaces her book talking about her lost ones:

IT’S STILL MY FAMILY […] I wanted to make the record of my life that nobody could revise: not a safe, clean version, but instead, a record of what things really looked like and felt like. But photography doesn’t preserve memory as effectively as I had thought it would. A lot of the people in the book are dead now, mostly from AIDS. I had thought that I could stave off loss through photographing. I always thought if I photographed anyone or anything enough, I would never lose the person, I would never lose the memory, I would never lose the place. But the pictures show me how much I’ve lost. AIDS changed everything. The people I feel knew me the best, who understood me, the people who carried my history, the people I grew up with and I was planning to get old with are gone. Our history got cut off at an early age.

[…] The pictures in the Ballad haven’t changed. But Cookie is dead, Kenny is dead, Mark is dead, Max is dead, Vittorio is dead. So for me, the book is now a volume of loss, while still a ballad of love.

I tried to keep it cool, but I could feel the tears coming.

We went on to talk about the work of David Wojnarowicz and Donald Moffett. Both artists called out systemic homophobia, as well as government complicity in the AIDS epidemic. Ronald Regan first publicly mentioned AIDS four years after the pandemic began. I thought about the immeasurable pain and loss caused by such silence, only to arrive at the conclusion that indeed time is non-linear. Silence equals death. History repeats itself all the time.

We ended our day at LGBT Center, where we saw Keith Haring‘s Once Upon a Time, a massive mural commissioned for the 20th anniversary of Stonewall. I could not help but laugh as I entered the bathroom filled with paintings of male genitalia and gay sex scenes. This was Keith Haring’s last major mural before his death from complications of AIDS in the following year. His humor and resilience remind me of how strong our community really is.

On my way home, I thought about Nan Goldin’s words. Indeed, our history is one marked by loss, while still a history of love.