The newest post in the blog series for the art history of New York City course, On/Off the Grid: Art and Cultures of Modern NYC, is being taught by Dr. Meredith Mowder. Jason Albuquerque, B.F.A. ’23, reflects on the class’ trip to Greenwich Village. The class visited the original Whitney Museum and Studio, Edward Hopper’s home and studio, the former site of the Cedar Tavern, the Triangle Shirtwaist Factory building (now part of NYU), Judson Memorial Church, and Washington Square Park. Yes, all these historic places are within a few blocks of each other!

Will I ever get used to the NYC subway system? I left home twenty minutes earlier than usual only to arrive late for class! By the time I deciphered the muffled noises coming from the speaker, I had already missed my station.

Panting, I arrive late at the first location of our class: the New York Studio School of Drawing, Painting, and Sculpture.

The pinkish art deco façade immediately transports me to a much different Greenwich Village than I had seen so far. Lost in a fast city of glittering screens, I found myself in a room filled with sculptures of torsos.

In 1907, Gertrude Vanderbilt Whitney, a sculptor and wealthy socialite, founded the Whitney Studio, in this very building. These four contiguous townhouses facing 8th street and their adjoining haylofts were essential in the development of American modern art. By fostering a community of artists, “The Whitney Studio Club” became a hub for American artistic and cultural dialogue. In her studio downtown, Whitney created, collected, and displayed work from some of the most famous American artists in history, at a time when budding American art scene faced rejection by the broader art world.

Our class met with Beatrice Chessman, the New York Studio School’s Development Officer, who guided us through the space they have done their best to preserve. It is invigorating to know that the studio is still being used for its original purpose. The “Studio Club” was (and remains) a place for artists to create and share artworks. While gathering in this space, artistic and personal exchanges could freely be made. The club’s essence and former glory continues to this day. I saw the past reflected in the present as artists passed me by, in these historic hallways, carrying their canvases and sculptures. Despite the aging interiors, the candor, vibrancy, and charm of these studio resonate.

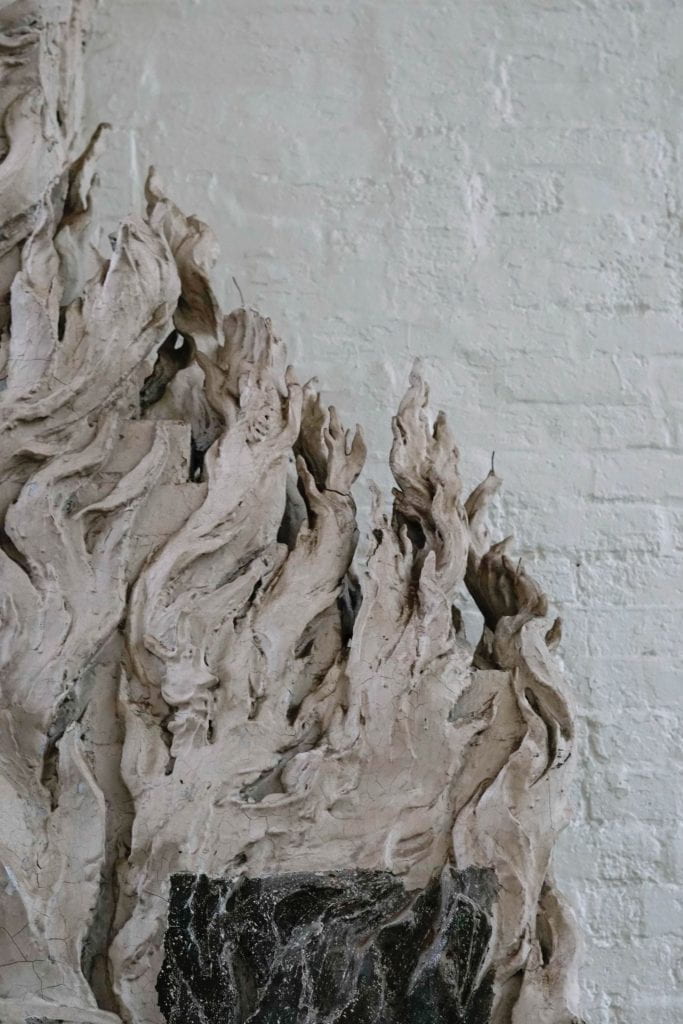

At the heart of the former Whitney Studio, in a social room now used for critique, was a breathtaking fireplace by Robert Winthrop Chanler. The 20 foot tall inferno of bronze and plaster extends to a ceiling of relief celestial bodies and mythical creatures. Magnificent nudes, sea monsters, snakes, deer, and dragons all appear under an anthropomorphized smiling sun.

We left the studio and walked down MacDougal Street, making a left on Washington Square Park, where we found ourselves in front of a beautiful brownstone building. A plaque on the right side explained that this was once Edward Hopper’s home and studio. As we sat on the stoop of the building, we discussed the surrealist quality of Hopper’s work. We looked at his painting titled Early Sunday Morning, from 1930. On the upper right corner of the painting is a looming black box suggesting the changing cityscape, from small 19th century row houses to skyscrapers and large apartment buildings. We also talked about what changes looked like in the art scene: the abstract expressionist action paintings of Jackson Pollock.

Now home to a CVS pharmacy, another historic site of that era could be found down the street: The Cedar Tavern.

Names like Jackson Pollock, Willem de Kooning, Mark Rothko, Allen Ginsberg, and Jack Kerouac would drink into stupor, trade ideas, and art criticism in this cheap bar. Legend has it that Pollock was banned for kicking in the bathroom door, and Kerouac for peeing in a sink.

We reflected on Allan Kaprow’s words about Pollock’s legacy: “Pollock, as I see him, left us at the point where we must become preoccupied with and even dazzled by the space and objects of our everyday life […].” We learned what that meant to the artists of their time. To move forwards, one had to realize that there were no boundaries between art and life. A perfect example was John Cage’s 4’33’’ performance, commonly known as the “silence piece.” In it, Cage created a three-movement composition where the score instructs performers to not perform their instruments. After sitting in complete silence for 4 minutes and 33 seconds on Edward Hopper’s stoop, we realized that the “silence piece” was everything but silence. With my eyes closed, I heard voices getting closer and fading away as people walked by; I heard motors and babies crying; the breeze and birds singing. Everything is music. Everything is art. Art and life are one.

Our next stop was the intersection of Washington Place and Greene Street. We look up, searching for the top floors. On March 25, 1911, one of the most infamous incidents in American industrial history happened at this location. One hundred and forty-six workers died in a fire that took over the top floors of the Triangle Shirtwaist Factory. Back then, it was common for companies to lock their employees in to maximize production and prevent the creation of unions. The workers of the factory were mainly teenage immigrants that worked 12 hour shifts every day.

As we walked back in the direction of Washington Square Park, I thought about the numerous lives lost in the name of profit. The tragedy led to the development of a series of laws and regulations to protect the safety of workers. But every single one of their lives was worth way more than their legacy.

Our class ended at Judson Memorial Church where we talked about the performance scene that ignited after the reign of abstract expressionism. In the basement of the church, artists revolutionized the way we looked at dance by blurring the lines between art and life. Allan Kaprow’s words about those who would come after Pollock turned into a prophecy: “Not satisfied with the suggestion through paint of our other senses, we shall utilize the specific substances of sight, sound, movements, people, odors, touch. […] People will be delighted or horrified, critics will be confused or amused, but these, I am sure, will be the alchemies of the 1960s.”

On the way back home, I returned to MacDougal Street’s Caffe Reggio for a cannoli. One of my favorite movies was recorded at this location. Sitting by the window where Larry Lapinsky and his intellectual friends talked about life over cigarettes and coffee in Next Stop Greenwich Village (1976), I stared at my cell phone. I thought about the Whitney Club, The Ashcan School, the Beat Poets, the Judson Dance Theater, and the countless groups of artists that have cascaded these streets, changing the course of popular culture. In a world where we are all connected, and yet so distant, I reflected on the importance of community and what is truly involved, only to realize that, indeed, it takes a village to make history.