As the semester comes to a close and the chaotic storm that is final reviews season subsides, 26 Broadway is left hollow, brushed clean of its students. Desks laid bare, no longer overflowing with scrap models, devoid of loose leaf trace paper and crumpled balls of discarded ideas. It’s a familiar calmness: the last days of the semester. It’s a time of reflection, a time to sit down and fill out course evaluations, and to think about the lows and highs of yet another busy semester for the books.

Possibly to find closure, but also to comment on the uniqueness of this fall, the first full semester in a COVID-19 world, I sat down to write this blog post; to talk, vent, reflect, and discuss a studio that will no doubt stick with me long after I graduate.

Peter Robinson’s studio, Housing + Sociality, was an experiment in collaboration. Every Monday and Friday, for six hours, the architecture studios at 26 Broadway transformed into a laboratory where architecture students worked alongside urban and regional studies students to form meaningful connections with fourteen high school students, whose lived experiences as young black men living and learning in and around Brooklyn formed the foundation of 14 unique and thoughtful projects.

At first, the collaborations were as choppy and awkward as the nature of the studio was foreign to all of us. Never before in our academic careers have we been asked to share ownership of our projects with “outsiders,” that is, non-architecture students. But it turned out to be that unfamiliarity that forced me to open my mind, to see that too often does the nature of an architectural education blind us from the implications of our work. For four years, although I’ve always attempted to put as much human-centered focus and thought into my designs as I can, in the end, the final product has been weighed on a value scale that determines not how human-centered or applicable it is, but how portfolio-worthy. The culmination of my semesters have not been to meet the world with my designs, but to submit a polished architectural project for NAAB accreditation. Of course, I’m speaking from personal experience, but discussions with my fellow classmates, both in architecture and in planning, have shared similar sentiments.

When asked what she has drawn from her collaboration with architecture students, my friend and classmate this semester, a senior in the URS program, responded, “[t]o speak frankly, I think architects also have much to learn from the urban planning field; I was surprised to learn how many architects hadn’t taken a planning class while many planners have taken architecture or architecture-related courses. The bridging of the gap needs to be an effort made by both sides. More cross-major classes would be beneficial.” She’s right. This is the first semester that I’ve been encouraged to overlap my design thinking with that of planning students.

Although disorganized at times, this studio has made the assertion that architecture and planning students should be well-connected and open to learn from one another. And by making a designer-client relationship the forefront of our design process, it also gave us a wake-up call that sometimes a design decision we think is best for the project does not align with the one that is best for the client, the inhabitant, the student, or the human.

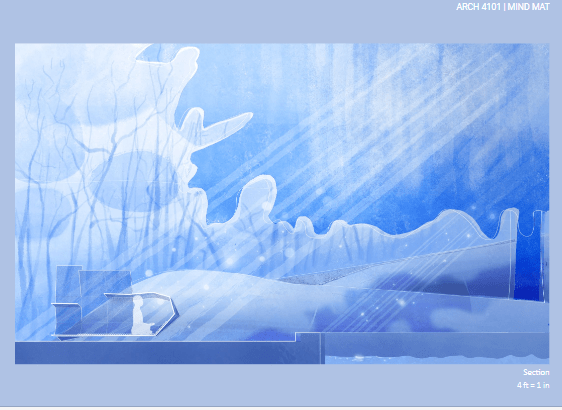

Peter definitively asked each of us to resist the temptation to design architecture the way we have been trained to design architecture. Instinctively, I planned to design a building with walls and a roof and windows, represented by plans and sections and elevations. But Peter repeatedly pulled me back to a 1 to 1 scale, to let the scale, form, and function of my design be born from hours of conversations with a seventeen year old black man named Anthony Todd, who likes to meditate and draw. In the end, my work may not have had the same design complexity or program as previous projects, but it reflected a deeply meaningful process of getting to know someone and as a result was resolute in concept and message.

Do I consider the experiment a successful one? I would say yes and no. Yes, because I was pushed to approach architectural design from a completely different angle and to overcome certain inhibitions that prevented me from exploring other ways to go about studio. Yes, in that I felt like what I was doing had a tangible impact on someone real (and his name is Anthony). On the other hand, the experiment failed because the relationship between architecture students and planners was an afterthought when it should have been a decisive variable. No glass walls were broken, merely scratched. Most of the collaboration between architects and planners happened towards the beginning; even then, the nature of the collaboration was superficial. Although placed in the same groups for projects, it felt like us and them, not us with them. Thus, while the attempt itself by the studio to nurture a collaboration between architects and planners was laudable, it warranted proper emphasis.