After a grueling week working on a final project for our urban design course, the masters of city and regional planning students were rewarded with a long awaited blockbuster tour of the Borough of Brooklyn. At the helm guiding the tour was AAP NYC’s executive director (and 18 year resident of Brooklyn) Bob Balder and new Cornell City and Regional Planning professor Tom Campanella (Brooklyn born, raised, and on-going inhabitant). In addition to living in Brooklyn, Tom is a scholar of Brooklyn having written about the city’s history and development.

After a grueling week working on a final project for our urban design course, the masters of city and regional planning students were rewarded with a long awaited blockbuster tour of the Borough of Brooklyn. At the helm guiding the tour was AAP NYC’s executive director (and 18 year resident of Brooklyn) Bob Balder and new Cornell City and Regional Planning professor Tom Campanella (Brooklyn born, raised, and on-going inhabitant). In addition to living in Brooklyn, Tom is a scholar of Brooklyn having written about the city’s history and development.

The tour kicked off at 9AM at the epicenter of the Brooklyn real estate development boom, the Barclays Center; a super-sized infill project. Over the last few years the Barclays stadium has drawn both acclaim and derision.

Located above the Long Island Rail Road’s Atlantic Yards, the stadium required the City of New York to exercise its power of eminent domain in order to create room for the new structure. Built by the developer Forest City Ratner, the building is a bridge between the 1970s aesthetic of reflective glass and rust cladding and 21st century engineering. The rust colored cladding is comprised of custom fabricated sections – each section custom built for its specific location on the building’s curvilinear exterior.

The next stop on our voyage was the Brooklyn Museum and Prospect Park. We began with the grand 1895 beaux art architecture of McKim, Mead, and White. Towering above Frederick Law Olmstead’s Eastern Parkway, McKim, Mead, and White’s Brooklyn Museum is part of a central complex of great public works that convey the power of the late 19th Century independent municipality of Brooklyn.

Bob, who lives across the street, spoke of the social function of the Brooklyn Museum. Specifically, the social impact of the museum’s 2007 remodel of its front entrance. The lobby is now open to the street by way of a glass rotunda that creates a space that is visually penetrated from the street outside. A gesture to the neighborhoods, the remodel coincided with the museum’s increased effort to engage a broader and more diverse audience. The facade now includes exterior steps that allow the public outside to walk over and around a now transparent lobby. There is also a great deal of seating and public space in the plaza in front of the museum. (We are told this plaza is where Bob’s daughter learned to walk).

From the museum and Eastern Parkway we walked into Prospect Park. Professor Campanella, who completed his masters of landscape architecture at Cornell, acquainted us with some of the landscape architecture principles in operation at the park. A paramount concept used by Olmsted is that of landscape compression and expansion. In designing the park, Olmsted tried to construct an impression for visitors who entered that they were leaving the busy city behind. In a transition that suggests passing through the wardrobe in C.S. Lewis’s Narnia, Olmsted created narrow funnel entrances into the park that still results in a feeling of bursting into nature.

Building on the funnel concept is the principal of creating a curved open space. The purpose of a bowl-like open space is to seal off the outside world as well as to pull the visitors further into the park. The underlying effect is that there is always another corner to venture around, another site to see.

Following the park visit, we fast forwarded in history to a renowned piece of 20th century public works, the Brooklyn Esplanade. Built under the reign of Robert Moses, the Esplanade sits atop three levels of stacked roadway. Cantilevered beneath the magnificent public space that is the Esplanade are two roadway trays containing the Brooklyn Queens Expressway (BQE). Then on the very bottom is a local road that used to provide essential access to the working waterfront.

The esplanade has arguably the best single view of the Lower Manhattan skyline in all of New York. It also provides an excellent perch from which to take in a bevy of new public amenities found in the developing Brooklyn Bridge Park. We learned from Professor Campanella that had many of Brooklyn’s most connected residents not lived in Brooklyn Heights at the time of the BQE’s construction, it is likely that the area would have been wiped from the map. In Moses’ drive to create vehicular routes throughout the city, few things stood in his way. The resultant esplanade represents a far more expensive roadway intervention than occurred in other neighborhoods that were also targeted for expressways.

Continuing the Moses-era tour, we visited Cadman Plaza Park, the site of the Brooklyn War Memorial. The park was designed by a team of architects, landscape architects, and city planners; one of whom was Gilmore Clarke, a Dean of Cornell’s College of Architecture, Art, and Planning in the 1940s. At the heart of the park is the WWII memorial to the more than 300,000 Brooklynites who served. In viewing the physical landscape, Campanella pointed out the London Plane trees set in a European inspired grid, and the forced perspective of the park’s conical shape. The narrowing of the park and its trees as one nears the far end of the site make the site seem larger than it actually is.

The next stop was the Brooklyn Navy Yard. Most of our visit occurred within the beautiful four story museum, known as BLDG 92. The museum tells the history of the Navy Yard site, which has a long history going all the way back to the original Native American inhabitants and the Dutch settlers. Following the Dutch, it was privately held by ship builders, serving as a mooring site for British prisoner ships during the revolutionary war. At its peak in the early 20th century, the site employed between 60,000 and 70,000 people as a US Navy Yard.

On top of the museum is a cafe where we had lunch overlooking the entire Navy Yard complex. This locale provided a particularly cool view of the complex’s gritty and multi-use characteristics, in addition to beehives atop several buildings’ rooves. The explanation for the apiary activity is an enormous urban agriculture operation on another one of the rooves in the Navy Yard. As a result, the beehive communities are part of a broader urban food production ecosystem.

From the Navy Yard we traveled up Kent Avenue through Williamsburg and Greenpoint. Along the way we saw the incredible high rise development that has grown along the waterfront. While cruising by the Greenpoint waterfront we made a quick stop at the WNYC Transmitter Park. This is a particularly special park as it was designed by our urban design professor Adam Lubinsky’s firm WXY Architects. A pleasant feature of the park is a new pier that juts out into the East River. I especially liked the pier’s railing.

From Greenpoint the next stop was to the southeast into Bushwick. Broadly considered to be the next Williamsburg, Bushwick is where the artists who originally made Williamsburg hip have relocated to. Like many trends in NYC, the flow of artists and galleries is following the path of a subway line. In this case it is the “L”.

Once we arrived, we stopped in with NURTUREart Gallery. This gallery focuses on emerging artists by providing the opportunity for solo and curated group shows, and thus some professional street cred. AAP NYC’s program coordinator, Brooke Moyse, a practicing artist in Bushwick, provided the introduction. Gallery director Marco Antonini provided an insightful perspective on what forces drove artists to Williamsburg and what forces subsequently pushed many artists and galleries to Bushwick. Nuancing his description, Marco explained how changes in zoning in Williamsburg were the primary drivers leading to a shift from artist’s live/work spaces to residential apartments. Antonini hopes the current land use in Bushwick will remain, and for the possibility that Bushwick’s distance from Manhattan will insulate it from the gentrified fate of Williamsburg.

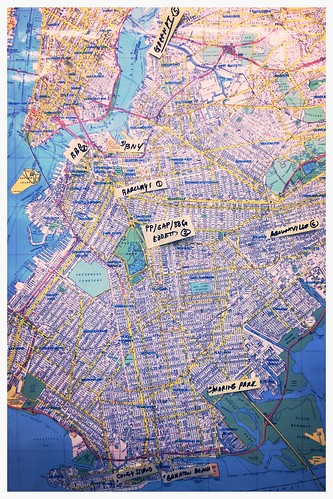

As the afternoon sun lowered, we loaded back onto our bus and made a beeline toward Brooklyn’s south. Along the way, we traveled through the neighborhoods of Bedford Stuyvesant, Crown Heights, and Marine Park, as well as to drive by Tom Campanella’s residence and childhood home in Marine Park.

Ultimately, our tour bus dropped us off in front of Nathan’s World Famous Hotdog Stand in Coney Island. Occupying the length of a block, this is where the internationally renowned hotdog eating competition occurs. More significantly, it is also where Bob Balder helped site NYC’s first minor league baseball stadium when he worked for the New York City Economic Development Corporation. While looking at the stadium, we learned from Bob about all the trials and tribulations involved in siting a major public facility on a short timeline.

A part of a New York City’s history, Coney Island represents an important urban space. Although not all that impressive or energized today, it was once the epicenter of leisure for the New York City middle class.

As the convergence point for four major subway lines (the D, N, F, and Q), Coney Island used to attract millions of people per year. Now the transit system provides significantly more capacity than is needed. Though it is an isolated site of disinvestment, Coney Island may be viewed as sign of larger trends. A shift in demand from residents and the shuttering of its three behemoth amusement parks paralleled the American shift towards the car and the suburbs after WWII.

While Coney Island is a tired-looking place today, there are signs of change. Bob’s baseball stadium is but one gesture combined with the work of consecutive New York City mayors to leverage investment into the area. As cities return to being the focus of American growth, Coney Island’s prominence will hopefully return too.

After braving the cold on the Coney Island boardwalk we hightailed it to our final stop, an Uyghur restaurant on the main strip of Brighton Beach. With the exception of one student in the MRP program, nobody knew what to expect from Uyghur cuisine. That student is from northwest China, which is one of the areas of Central Asia where Uyghur people live. The restaurant is a longtime Campanella favorite and it lived up to the hype! Lots of lamb, great noodles and dumplings, and spectacular bread.

If only we had time for “best of tours” of the other four boroughs!