Huitlacoche

For a gardener, Ustilago maydis can certainly be a little scary, especially if you don’t know what it is. Imagine going out to your sweet corn patch and finding this! No wonder it has been called “Devil’s corn.” But once you learn a little more about this smut, it becomes an intriguing, and maybe even desirable addition to the garden.

In the fungal phylum Basidiomycota, smuts are distant relatives of true mushrooms. They are named for the masses of black dusty spores they produce, which resemble smut, or if you’re not into archaic language, soot. There are more than 1,000 species of smut and they all parasitize flowering plants, infecting more than 75 families.

Most U.S. corn farmers consider this fungus a disease. Infestations are more common after rains preceded by dry, hot summers. Infection causes insufficient chlorophyll production, reduced growth and most disturbingly, the appearance of those nasty looking spore-filled galls. These things could have come right out of a bad science fiction movie. Each one is actually a kernel of corn that has been co-opted by the fungus, kind of like how a virus takes over its host’s cells and uses them to produce more virus. Crop losses are less than 5 percent. U. maydis‘ biggest impact on sweet corn farmers is that it prevents mechanical harvesting, because if one infected ear gets into the harvester it can cover all the healthy ears with an unappealing black mess. There are no pesticides approved for treating seeds or plants, but some corn varieties are more resistant than others (Silver Queen is highly susceptible, for example, whereas Silver King is more resistant).

In Mexico, however, farmers smile when they see a smut infestation because the fungus, considered a delicacy, fetches a higher price than the corn. In an attempt to gain mass acceptance north of the border, foodies have re-branded it the “maize mushroom,” though it’s not a true mushroom. “Mexican truffle” might seem more accurate, because truffles aren’t true mushrooms either, but they belong to a completely different phylum, the Ascomycota. The ancient Aztecs, who believed it possessed mystical, even aphrodisiac powers, simply called it huitlacoche (wee-tlah-KOH-cheh) variously translated as “raven excrement” or just plain “black shit.”

Despite that translation, huitlacoche is highly regarded by gourmands. I was eager to try it and picked a bunch from my corn patch. Like other mushrooms, only the younger specimens should be eaten. Rick Bayless, author and chef of Topolobampo in Chicago, gives this advice:

Pick it when it feels like a pear starting to ripen, when there’s a little give to it. Too firm and it will be bitter. Too late, when the thin skin of the gall breaks if you rub it, and it will taste really muddy.

Unfortunately, I discovered that huitlacoche is highly perishable. By the time I got around to making soup , mine was too far gone. I learned later that I should have kept it on the cob with the leaves, and as with true mushrooms, not in plastic. That way it can be refrigerated for 7 to 10 days. For longer preservation, huitlacoche can be frozen, dried or canned. To freeze, just place the galls in a zip lock bag and pop in the freezer for up to a year, no blanching necessary.

You don’t need to grow your own corn to try huitlacoche. With the popularity of nouvelle Mexican cuisine, canned huitlacoche is increasingly available in ethnic food markets, though like anything else, fresh is always better. Either way, anyone adventurous enough to try it should know that the Zuni used huitlacoche to induce labor (pregnant women beware). Its medicinal effects are similar to ergot, another fungus once used to induce abortions, but weaker.

You don’t need to grow your own corn to try huitlacoche. With the popularity of nouvelle Mexican cuisine, canned huitlacoche is increasingly available in ethnic food markets, though like anything else, fresh is always better. Either way, anyone adventurous enough to try it should know that the Zuni used huitlacoche to induce labor (pregnant women beware). Its medicinal effects are similar to ergot, another fungus once used to induce abortions, but weaker.

When cooked, huitlacoche leaks an inky liquid that turns everything else black. Others have compared huitlacoche to several European wild mushrooms. Its flavor is described as earthy, pungent and a cross between mushroom and corn. It has been used in tamales, quesadillas, appetizers, and even ice cream. Nutritionally, it is relatively high in unsaturated fatty acids and protein, with adequate amounts of all essential amino acids.

The ancient Aztecs are said to have scratched their corn stalks at the soil to encourage the growth of huitlacoche. Professor Bill Tracy and Graduate Assistant Camilla Vargas at the University of Wisconsin in Madison are investigating more modern methods for the deliberate inoculation of corn to propagate huitlacoche. Researchers there also worked with the Troy Community Farm to research developing a market for huitlacoche. They found that chefs were more enthusiastic than their Anglo customers and would be interested in buying only a few pounds a week–not enough to justify the cost of delivery. They concluded that selling frozen huitlacoche wholesale to ethnic groceries and restaurants would be more profitable. If the Devil’s corn turns up in your garden next year, don’t get scared, just give it a try.

- Banuett, F. 1995. Genetics of Ustilago maydis, a fungal pathogen that induces tumors in maize. Annu. Rev. Genet. 29, 179–208.

- Christensen JJ. 1963. Corn smut caused by Ustilago maydis. Monograph No. 2. St. Paul, Minnesota: American Phytopathological Society. 41 p.

- Damrosch, Barbara. Corn Smut: A Reputation Redeemed The Washington Post, February 15, 2007; Page H08.

- Stivers, Lee. Crop Profile: Sweet Corn in New York Cornell Cooperative Extension.

- Valverde, M.E. and O. Paredes-Lopez 1993. Production and evaluation of some food properties of huitlacoche (Ustilago maydis). Food Biotechnology 7(3): 207-219.

- Zepeda, Lydia, The Huitlacoche Project: A tale of smut and gold, Renewable Agriculture and Food Systems: 21(4); 224–226.

Image of corn smut in action by the author.

Can o’ corn smut image by Smokin Doc Thurston.

Riddled with ringworm?

The word “Zoonoses” evokes elephant trunks and zebra muzzles, but the reality is less picturesque, it is the term for diseases normally occurring in animals which can be transmitted to humans. Ringworm, or Tinea as it is known in people, is such a disease, and has nothing to do with worms. The term comes from the Latin word Tinea, which refers to worm-like moth larvae that chew circular holes in woolen blankets—resembling the circular skin lesions typical of this condition.

Ringworm is caused by a group of 40 species of fungi that belong to the odd ascomycete order Onygenales. These dermatophytes (literally “skin plants”) don’t actually invade living tissue, but the outer, keratin-rich layer of hair and skin and nails. Keratin is a fibrous structural protein, one of the most abundant and stable animal proteins on earth, which is targeted for breakdown by fungal keratinases. These are the only fungi which have evolved a dependency on humans or animals for survival on keratin. Micosporium canis, Trichophyton verrusosum, and Trichophyton metagrophytes are the most important species responsible for human infections.

Ringworm is quite contagious, and can be spread from direct contact with an infected animal, soil, hair or skin shed from an infected animal, or fencing, tack, or grooming tools. The spores are viable in shed skin or hair for months or even years. Any part of the body can be infected but exposed areas of the face, neck or arms where there is likely to be abrasion to aid fungal colonization is the most common. Human to human spread is rare. Microsporum canis moves from dogs to humans. And many human infections come from our feline friend, the domestic cat, which in turn can get it from rodents they prey on. Up to 90% of cats display no visible ringworm symptoms, so it can be unknowingly passed on—one nurse infected five babies in a neonatal nursery before the connection with her cat was made.

Your doctor can check for ringworm with a simple office test using a Wood’s light (a filtered UV light) to reveal the fungal spores as they emit bright bluish-green fluorescence. The ringworm fungi are opportunistic pathogens, often starting on young or compromised animals at weaning. Children ages 4 to 11 are most often infected, with a higher incidence on males which isn’t seen in animals.1 Now I know why both my sons had this and the girls avoided it while doing the same things! The rash and itching associated with ringworm is due to the fungus’s manner of producing enzymes to digest its food externally, rather than internally, as most other organisms do. These fungi have developed to survive on their animal hosts without causing excessive immune reactions, but on human skin, an inflammatory response may develop from exposure to the enzymes released by the fungi and a raised red, itchy rash is often the result. This mimics a bacterial infection, and is often misdiagnosed as such. Often bacteria do invade this irritated area, making treatment more confounding and painful, may I add from experience. Since this is not a reportable disease, and often no treatment by a physician is sought, the exact prevalence is not certain.

In cattle, ringworm infection often occurs during fall or winter months when animals are moved into barns and there is crowding, higher humidity, and less sunlight. Ringworm infection often starts around the eyes and can cause scaling and a grayish crusting of the head in calves, and chest or brisket of older animals. The moisture around the eyes enables the fungal spores to adhere and start to grow, and because of cattle’s use of their head to determine their rank in a group, it is often abraded and more easily colonized. Most feeding systems require the animals push their heads through an opening to eat which facilitates spore transmission and spread. It is usually a self-limiting disease of 1 to 4 months, but treatment is sought when it’s time for the county fair and a calf isn’t allowed to go because it is a communicable disease (and is your child’s only calf) or it becomes a threat to stressed animals. A scrub brush with dilute bleach is often prescribed and oral or topical antifungal treatments work, but must be continued for long periods of time and can be harmful to pregnant animals. Some work has been done using wood rotting fungi which have antifungal activity against these dermatophytes with Gleophyllum trabeum being the most effective.3

A vaccine has been developed for cattle and confers almost 100% protection against T. verrucosum using an attenuated form of the fungus. The best protection results from using a live, virulent strain.6,7 The vaccine was developed by studying the antigens produced during spore formation and early hyphal growth—these compounds stimulate a cell-mediated immune response rather than antibody formation more consistent with a chronic disease.5 The vaccine approved for cats doesn’t have the same effectiveness and although it reduces symptoms, the fungus isn’t completely controlled. Our vet clinic doesn’t even offer this for cats.

With the popularity of petting zoos, fairs, and other areas of contact of young children with animals in public settings, there is a movement to educate vendors, staff, and visitors of the possibility of zoonotic diseases like ringworm. Simple precautions such as hand washing, especially before entering areas where food is sold, can keep this from being a public health problem.4 On farms, it is harder to control, but with an understanding of modes of transmission, sanitation, and vaccination when appropriate, the disease’s incidence on calves, dogs, cats and kids can be reduced.

- Acha, Pedo N., Boris Szyfres. Zoonoses and communicable diseases common to man and animals (3rd edition). Pan American Health Organization WHO. Washington, D.C. 2001.

- Ainsworth, Chmel L., Pepin, G.A.Fungal Diseases of Animals. Zoonotic dermatophytosis. Veterinary Record 118, 1986.

- Gwak, Ki-Soeb. Antifungal activities of extracts from liquid culture media of wood-rotting fungi against dermatophytes. Abstract, 232nd ACS National Meeting. Sept 10-14, 2006.

- Compendium of measures to prevent disease associated with animals in public settings 2005. CDC 2005 54

- Smith, JM, Griffin, JF. Strategies for the development of a vaccine against ringworm. J Med Vet Mycol 1995 33(2) 87-91

- Kocik, T. Evaluation of the immunogenic properties of live and killed vaccines against trichopytosis of guinea pigs and calves. Pol Arch Weter 1982, 23(3) 95-107.

- Rybnikar, A, Chumela, J, Vrzal, V. The development of immunity after vaccination of cattle against trichcophytosis. Vet Med 1989 34(2) 97-100.

Pictures thanks to Belinda Thompson, and courtesy of www.doctorfungus.org, 2007.

Beware! The Slime Mold!

If you are a B horror movie fan, chances are you’ve heard of The Blob. The original is a 1958 teen thriller that spawned a 1972 sequel, Beware, the Blob! as well as a 1988 remake. Each features a set of misunderstood teenagers who witness the amorphous horror that is The Blob. Skeptical parents and authority figures refuse to take the threat seriously, and, of course, a lot of people get absorbed and digested by The Blob. The star of the films is a gooey, slimy mass that crawls around town digesting people and growing ever larger.

But what type of creature is The Blob? An explanation was not offered until 1988, when Dr. Meddows reveals that The Blob is the result of a government experiment to create a germ warfare weapon by isolating a virus and bacteria in space. But should we trust Dr. Meddows, who states “Dinosaurs ruled our planet for millions of years and yet they died out almost over night. Why? The evidence suggests that a meteor fell to Earth carrying an alien bacteria.” Dr. Meddows clearly has a few of his facts mixed up. So, what is The Blob?

But what type of creature is The Blob? An explanation was not offered until 1988, when Dr. Meddows reveals that The Blob is the result of a government experiment to create a germ warfare weapon by isolating a virus and bacteria in space. But should we trust Dr. Meddows, who states “Dinosaurs ruled our planet for millions of years and yet they died out almost over night. Why? The evidence suggests that a meteor fell to Earth carrying an alien bacteria.” Dr. Meddows clearly has a few of his facts mixed up. So, what is The Blob?

Scientific (fictional) evidence suggests that The Blob is the plasmodial phase of a slime mold! Slime molds may seem moldy, but they aren’t fungi at all! They lack chitinous cell walls, have mobile stages in their life cycle, and digest food whole instead of secreting enzymes like most fungi. Today we recognize slime molds as protists (mostly microscopic animals), not fungi, but because mycologists have traditionally studied them, they continue to pop up in mushroom field guides and mycology textbooks.

What does plasmodial phase mean? Slime molds begin their life cycle as a single, mononucleate cell. This cell can switch depending on its environment between a swimming cell with flagella and a crawling amoeba. It swims or crawls around in search of food, until one day it decides to mate and fuse with another single cell. Fusion is what distinguishes the plasmodial from cellular slime molds. Plasmodial slime molds crawl around, ingesting bacteria through absorption and digesting them intracellularly, growing and growing into a large multinucleated mass, the plasmodium. The plasmodium has no cell wall, and no membrane dividing its many nuclei: it is a single giant cell with many nuclei enclosed by a single membrane. Cellular slime molds are actually many single cells aggregating and acting as a plasmodium, but they maintain their cellular integrity.

Hopefully you have already noticed a few similarities between The Blob and a plasmodial slime mold. The Blob’s feeding habits are quite like a slime mold. Slowly crawling around, the Blob searches out its food, surrounds it, and absorbs it. Slime molds do the same thing, even absorbing particles they cannot digest and passing them out the other side, always hoping to engulf more bacteria. Is this any different from The Blob absorbing an entire phone booth to eat the waitress inside? Of course, The Blob has evolved to eat people (and kittens), not just bacteria, but this is appears to be a common mutation acquired in space.

Hopefully you have already noticed a few similarities between The Blob and a plasmodial slime mold. The Blob’s feeding habits are quite like a slime mold. Slowly crawling around, the Blob searches out its food, surrounds it, and absorbs it. Slime molds do the same thing, even absorbing particles they cannot digest and passing them out the other side, always hoping to engulf more bacteria. Is this any different from The Blob absorbing an entire phone booth to eat the waitress inside? Of course, The Blob has evolved to eat people (and kittens), not just bacteria, but this is appears to be a common mutation acquired in space.

The Blob’s movement and morphology also strongly resemble that of a slime mold. Amoeboid, it branches out into many finger-like pseudopods in search of food, flowing towards its prey. The video below is of an earthbound plasmodial slime mold, Physarum polycephalum. It has been colored to better resemble The Blob (which ranges from blood red to blue) but earthly slime molds can be a variety of bright colors. Notice how the cytoplasm streams in one direction and then another in a rhythmic tide. This resembles The Blob’s irregular invasion and retreat in the movies, absorbing characters and disappearing from the scene, causing the plot to lay stagnant.

Quicktime 5+ movie

Time lapse video of a plasmodium of Physarum polycephalum by Kent Loeffler. We tinted the normally yellow plasmodium blue for a sci fi effect! This plasmodium rampaged around a petri dish for 10 days, engulfing oat flakes.

Have I convinced you that my slime mold theory of The Blob is more compelling than Dr. Meddow’s bacteria-virus hypothesis? In addition to being microscopic, bacteria have cell walls, are not motile on dry land, and do not move in a branched manner. Having a virus around would probably kill the bacteria, not mutate them into a monster, even in outer space. It’s far more likely that a slime mold climbed into Dr. Meddow’s experiment due to his shoddy sterile technique, ate the bacteria inside, and acquired a mutation that allowed it to grow larger than a tank and eat people. Many homeowners and gardeners have already made the connection between The Blob and slime molds, complaining about blob-like creatures invading their lawns. They should be thankful these slime molds are content to feed in their lawns, and not crawl inside for tastier prey.

The Blob in action in the 1988 remake The Blob.

Lyrics to the theme from the 1958 The Blob:

“Beware of The Blob!

It creeps, and leaps, and glides and slides,

Across the floor, right through the door

And all around the wall.

A splotch, a blotch,

Be careful of The Blob!”

Sources:

- The Blob Site, http://theblobsite.filmbuffonline.com/index.htm. Accessed 10-22-07.

- Macbride, T. H. and Martin, G. W. The Myxomycetes. (New York, The Macmillan Co.) 1934.

The elusive dog’s nose fungus

I led a mushroom walk in the woods a few weeks ago for the Finger Lakes Land Trust. It was a lovely Fall day, and my little group found many handsome and curious mushrooms. Among them was one that was handsomer and curiouser than the rest. Its finder Susan quickly dubbed it the “dog’s nose fungus.” Another member of the group argued that it better resembled a small and delicious chocolate tart, but it was getting close to lunch time and I’m not sure that he was thinking clearly.

For those of you unacquainted with the texture (and the cold wet feeling) of a dog’s nose, I have included Exhibit A, a photograph of the nose of Ebumu. Our find resembled a dog nose in its bumpy texture, its blackness, and also in its glistening wetness–a wetness produced from the fungus itself without help from rain or dew. It was, coincidentally, almost exactly the size of my dog’s nose. Here it is:

Turns out this is Peridoxylon petersii, an uncommon fungus in these parts, though it is perhaps commoner in the southeastern US. We have no records of it at all in the Cornell Plant Pathology Herbarium (CUP). It’s been found just a few times ever by participants in the Northeast Mycological Foray3, and the New York Botanical Garden has only a handful of New York records4. It’s also known as Camarops petersii—whether you put it in the genus Camarops or the genus Peridoxylon depends on whether you think it’s distinctly different enough from other species of Camarops to warrant its own genus1. A recent paper by L. Vasilyeva and colleagues2 presents a good argument for calling it Peridoxylon, and I’m sticking with them.

This fungus is a large perithecial ascomycete, not a mushroom. Its fruiting bodies grow on rotted logs (probably oak, in this case), and presumably the mycelium is breaking down the wood somehow. Its black spores are produced just below the glistening upper surface in tiny pear-shaped structures called perithecia. Most of its relatives make minute fruiting bodies too small to see with the naked eye. The large fruiting body of P. petersii includes many individual perithecia–you can tell they’re lurking just below the surface from the little bumps, which are where the perithecia open to allow the spores to shoot out.

So here’s an apparently rare fungus (at least for New York). It turns out that it’s hard to say for sure how rare it is, because New York doesn’t have a list of rare fungi, nor even a list of the fungi known from the state. I’m thinking it’s time to start developing such lists, at least for macrofungi. It’s a tough job, because fungi are hard to survey for (being both ephemeral and small), and they’re hard for ordinary folks to identify. I think it’ll take a community effort, and I’d like you folks to help.

I’m going to start with a simple request:

which macrofungi do YOU think are rare in New York?

Leave me a comment or get in touch and we’ll roll up our sleeves and get started.

- Nannfeldt, J. A. 1972. Camarops Karst. (Sphaeriales-Boliniaceae), with special regard to its European species. Svensk Botanisk Tidskrift 66:336-376.

- Vasilyeva, L. N., S. L. Stephenson, and A. N. Miller. 2007. Pyrenomycetes of the Great Smoky Moutnains National Park. IV. Biscogniauxia, Camaropella, Camarops, Camillea, Peridoxylon and Whalleya. Fungal Diversity 25:219-231.

- The Northeast Mycological Foray (NEMF) Lists, maintained online by Gene Yetter. (thanks Gene!)

- Go ahead, search for Camarops petersii in the New York Botanical Garden herbarium. (thanks again, Gene!)

Supermarket Mycology. Flyspeck disease of apples

Welcome to Supermarket Mycology, an irregular series of posts on fungi you might well encounter in your everyday life. We’ve already kicked things off handsomely with time lapses of rotting strawberries and lemons, and of course there was the cautionary tale of the moldy maple syrup. Fungi are more ubiquitous than most people imagine; supermarkets house a surprising number of both good (tasty or useful) and bad (unwanted or ugly) fungi.

Today’s fungus grows on apples, causing a disease named flyspeck. The word flyspeck is a polite way to say fly poop, but that’s not what’s going on here. To flyspeck something is to scrutinize it in minute detail, just as I will shortly flyspeck this blog post for tyypos. A flyspecked apple is something else altogether, though you often do have to look closely to see the fungus.

Quicktime 5+ object

Rotating, zoomable image by Kent Loeffler

The little dots on our apple are the typical sign of flyspeck disease. They’re the minute fruiting bodies of the fungus Zygophiala jamaicensis. (AKA Schizothyrium pomi). They, and in fact the whole mycelium of the fungus, are growing superficially on the cuticle of the apple. This image shows a pretty bad case. Most of the time, my flyspecked apples have just one or two artistic little aggregations of specks on them. I personally have eaten very many of these, with no apparent ill effect. You have too (unless you are one of those compulsive apple peelers, like my old neighbor Betty2).

You might observe that these little black dots are not terribly distinctive, and you’d be right. From a study done by Batzer and colleagues,1 we have learned that other fungi make little flyspecks, too. An unnamed Ramularia sp. causes “compact speck,” and a Dissoconium sp. causes “discrete speck.” You must look at your specks up close with a hand lens (at least) to tell which you’ve got. The dots are the beginnings of fungal fruiting bodies–before the fungus decides to make these, it exists as an invisible colony that grows stealthily on the apple cuticle. The proto-fruiting bodies are waiting ’til next Spring to make and discharge their spores.3

Moving beyond flyspeck, which often isn’t all that noticeable, we come to sooty blotch. In our image, you can see this disease as diffuse dark clouds and blotches. It too is caused by a (literally) motley crew of fungi related to the flyspeck fungi. Sooty blotch fungi also grow superficially on the apple; both sooty blotch and flyspeck favor the same, humid conditions for their development, so we often speak of them together (SBFS). Although neither disease affects the quality of the apple flesh, apple growers dislike them because, well, would you buy an apple that looked like this?

![]()

1. JC Batzer, ML Gleason, TC Harrington, LH Tiffany. 2005. Expansion of the sooty blotch and flyspeck complex on apples based on analysis of ribosomal DNA gene sequences and morphology. Mycologia 97(6): 1268-1286.

2. And let me just take the opportunity to say again, Betty, how sorry I am that my dog ate your box from Land’s End with the blue dress in it, after it was misdelivered to my house. The dress wasn’t much damaged by the dog, but I feel really bad about the truck that ran over your mailbox after we’d put the chewed box into it–apparently a bee had gotten into the cab. Just not our lucky day, I guess. Did you ever get a new dress?

3. D Cooley. 2007. Summer diseases. Scaffolds Fruit Journal 16(19).

Furia ithacensis

I know of only three fungal species named for Ithaca: Cordyceps ithacensis, Humaria ithacaensis, and voila! our fungus of the day, Furia ithacensis. They’re all named for Ithaca, New York, not the arguably more famous Greek Island (remember The Odyssey? Odysseus came from Ithaca).

I’ve already met C. ithacensis and had the sad duty of relegating it to synonymy with Cordyceps variabilis.1 I’m still looking for Neotiella ithacaensis (=Humaria ithacaensis), a small cup fungus that grows on liverworts (I’ll keep you posted). This week’s find was the spectacular Furia ithacensis, which I encountered for the first time, ever, right here at my home.

So here’s Furia ithacensis doing its thing, which is killing snipe flies.2 Snipe flies are true flies in the family Rhagionidae. They spend much of their life being nasty, bristly, wriggly maggots in wet places, then transform into elegant big-eyed flies. They’re sometimes called down-looking flies. I hear that out west they look down on you, then fly over and bite you. Our eastern flies are tamer.

I’d stumbled onto a devastating epidemic among snipe flies. I found them on the undersides of witch hazel leaves, wings outstretched, bound to the leaf by a hundred hyphal ties. Not just ordinary hyphae, either, but specialized hyphae called rhizoids that grab the leaf via a serious sucker-like holdfast. I found perhaps a few dozen victims on the hazels along a small stream. The cadavers were in various states of disrepair–some actively discharging fungal spores (left), others long-dead and salted with granular resting spores that have peculiar wrinkled coats.

You can easily learn to recognize entomophthoralean fungi. Victims typically die while clinging to something–in this case the undersides of leaves. For a brief time, often early in the morning, the unfortunate host swells up and fungus erupts from the softer membranes to discharge a distinctive halo of shot spores. If you find your cadaver after that, identification can be difficult because these fungi quickly subside after discharging all their spores. If you have a good hand lens, you’ll come to recognize their distinctive glassy or waxy appearance–more translucent than “normal” molds.

Recognizing these fungi is one thing; identifying them can be tricky. If you are a good entomologist, identifying the host will help in narrowing down the identification, because each of these species is pretty finicky about which insects it will kill. Furia ithacensis, for example, is known only from flies in the family Rhagionidae. Otherwise, you’ll need a microscope to look at spore shape, sporophore branching, rhizoids, and stuff. The spores in the photo are stained with a special dye called aceto-orcein (derived from lichens!), which stains the condensed chromatin in the nuclei red. This dye can help determine which of the five families of the Entomophthorales is home to your specimen, and help you count the numbers of nuclei per spore (family Entomophthoraceae, and one, in this case).

If I were a birder, I’d call this fungus a “good bird,” because it is not commonly reported, has a personally relevant name, and is uber-cool. If I were a birder, I would be keeping track of my “good birds” on my “life list.” If I were a birder, I’d be able to download a list of all birds known from North America. For fungi, we aren’t even close to comprehending North American biodiversity, and we’re discovering new species and genera all the time. For me, that makes mycology all the more exciting. Go ahead, start a life list. Maybe yours will include something that is brand new.

- 1. Hodge, K. T., R. A. Humber, and C. A. Wozniak. 1998. Cordyceps variabilis and the genus Syngliocladium. Mycologia 90:743-753.

- 2. J.P. Kramer. 1981. A mycosis of the blood-sucking snipe fly Symphoromyia hirta caused by Erynia ithacensis sp. n. (Entomophthoracee). Mycopathologia 75: 159-164.

- To discover which fungi are named after your home town, do a search in Index Fungorum, an invaluable compendium of fungus names. I searched for “ithac” as an epithet. Next just go outside and find them…

- Cordyceps ithacensis Balazy & Bujak is now best known as Cordyceps variabilis, alas; Humaria ithacaensis Rehm is now known as Neotiella ithacaensis; and our fungus of the day, Furia ithacensis started out as Erynia ithacensis Kramer.

Photos: KT. Hodge (the glorious fly) and R.A. Humber (stained spores).

The Dancing Nematode and the Helicospore

When you study tiny things, that first glance through the microscope is like opening an unexpected birthday present. What you want is to sit down at the microscope, look at the slide, and go “WOW!!!!” As hinted in my ruminations on Linder’s monograph, and in Kathie’s BioBlitz post, the helicosporous hyphomycetes have been responsible for their share of wows. I always make a point of showing them to visitors, especially nonmycologists. In fact, Mrs. FAM was once exposed to helicospores in my attempt to seduce her into my esoteric world.

Well, one day I was looking at a really wet bark specimen and I saw this:

Quicktime 5+ movie

What in heaven’s name was going on? What is all that wiggling? Well, when you spend a lot of time looking at rotting stuff, you get used to the aerial dance of nematodes, waving their glassy noses around in the air like cobras charmed by some microscopic swami. But these nematodes (and there were lots of them struggling like this), looked like they had been dipped in sugar. When I picked one up and put it on a slide, this is what I saw:

What in heaven’s name was going on? What is all that wiggling? Well, when you spend a lot of time looking at rotting stuff, you get used to the aerial dance of nematodes, waving their glassy noses around in the air like cobras charmed by some microscopic swami. But these nematodes (and there were lots of them struggling like this), looked like they had been dipped in sugar. When I picked one up and put it on a slide, this is what I saw:

All well-raised mycologists know about fungi with a special talent for grabbing and consuming nematodes. A few species make spectacular constricting rings to grab these wandering nitrogen-rich delights. The delicious oyster mushroom Pleurotus is only one of the basidiomycetes that makes little microscopic temptations referred to by George Barron as “lethal lollipops.” Science fiction fans will recall the famous Piers Anthony novel Omnivore, which features a planet where all organisms in all ecological niches evolved from fungi. In one dramatic scene, the heroes are menaced by gigantic nematodes and then rescued by the constricting ring traps of a heroic Arthrobotrys.

But helicosporous fungi are not known to trap or consume nematodes. There was no obvious hyphal growth in my dead nematodes, and sure, it is possible that there were other nematode trapping fungi around (you can see some smaller, non-helicoid spores in the photo).

But this is a unique observation, shared with you for free in an attempt to stimulate some original research on your part. Was this a one-off thing or do these helicosporous hyphomycetes have a habit of doing this? How are they killing the nematodes? Do they make toxins? Here’s another thing… most nematode killing pesticides have been banned. Could these helicosporous fellows be making something with commercial potential? There could be millions of dollars in here for you. All I ask is that you remember the beautiful helicospores each time you cash your royalty cheque.

There is another box here on my desk from Finland. Again, I am afraid.

Thanks to Kent Loeffler for translating the video into a web-friendly format.

Bioblitz Final Report

Classes have just ended here and it is the time of final reports, term papers, assignments. For my part, I’d like to tell you about our bioblitz results.

We had about 46 participants (a handful of them kids). I asked each person to estimate how many species we might identify, and the answers ranged from 10 to 2760 species. I have a prize–David Wagner’s awesome caterpillar book for the closest estimate (243) by Dawn! Among us we identified 266 species. This is great. Here are some highlights.

We had about 46 participants (a handful of them kids). I asked each person to estimate how many species we might identify, and the answers ranged from 10 to 2760 species. I have a prize–David Wagner’s awesome caterpillar book for the closest estimate (243) by Dawn! Among us we identified 266 species. This is great. Here are some highlights.

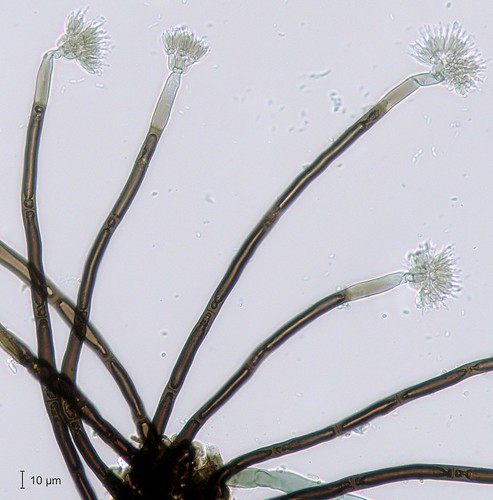

First, of course, a few fungi. Like I said, mostly we found last year’s fruiting bodies and only one fresh mushroom. A few especially handsome microfungi turned up. Above left, the helical spore of Helicosporium griseum (nice, since FAM was just talking about Linder’s helicosporous fungi). Also, a handsome zygomycete on deer poop, Pilaira anomala (yellow-grey pinheads), and the stately Thysanophora penicilloides (brown toilet brushes–forgive me, Bryce).

We found much more than just fungi…

The ickiest things we found were these flatworms, which belong to the phylum Platyhelminthes. Four flatworms arrived at headquarters early in the morning, captured by children who called them wigglies. The flatworms sulked in their dish until the late afternoon, when Norm spotted them and insisted on feeding them some worms. After that things got interesting very quickly.

The ickiest things we found were these flatworms, which belong to the phylum Platyhelminthes. Four flatworms arrived at headquarters early in the morning, captured by children who called them wigglies. The flatworms sulked in their dish until the late afternoon, when Norm spotted them and insisted on feeding them some worms. After that things got interesting very quickly.

The flatworms found the worms, then emptied their guts onto them–a rich soup of digestive enzymes including some serious collagenases. The worms pretty much dissolved over the next hour. By the next morning, the three flatworms had almost finished off the four worms, leaving a little froth and a bit of the 4th pink worm. The flatworms are called Bipalium adventitium, and turn out to be pretty nasty worm predators. In learning about flatworms from Norm, I also learned that the go-to guy on invasive flatworms is Peter Ducey, a professor just up the road in Cortland, NY (see this paper of his for more flatworm info). I thought I’d send him these specimens, but then – whoops! – I forgot about them for a couple of days. And it turns out that even flatworms cannot survive when confined in a soup of digestive juices for very long. There was nothing left of them. Sorry, Peter.

The flatworms found the worms, then emptied their guts onto them–a rich soup of digestive enzymes including some serious collagenases. The worms pretty much dissolved over the next hour. By the next morning, the three flatworms had almost finished off the four worms, leaving a little froth and a bit of the 4th pink worm. The flatworms are called Bipalium adventitium, and turn out to be pretty nasty worm predators. In learning about flatworms from Norm, I also learned that the go-to guy on invasive flatworms is Peter Ducey, a professor just up the road in Cortland, NY (see this paper of his for more flatworm info). I thought I’d send him these specimens, but then – whoops! – I forgot about them for a couple of days. And it turns out that even flatworms cannot survive when confined in a soup of digestive juices for very long. There was nothing left of them. Sorry, Peter.

Moving on to happier tales, I report with enthusiasm and pride that the four moss and lichen people should win the prize for being the most earnest and productive participants. They identified 62 species of mosses, 14 liverworts, and 20 lichens, plus a bunch of herbaceous plants.

Moving on to happier tales, I report with enthusiasm and pride that the four moss and lichen people should win the prize for being the most earnest and productive participants. They identified 62 species of mosses, 14 liverworts, and 20 lichens, plus a bunch of herbaceous plants.

Who knew there were so many liverworts lurking around here?  Among others, they found a liverwort named Frullaria making its exquisite sporophytes (right, see its slinky-like elators, which have lovingly flung out the spores?).

Among others, they found a liverwort named Frullaria making its exquisite sporophytes (right, see its slinky-like elators, which have lovingly flung out the spores?).

Also, a good number of lichens. There was a big Peltigera species, which I always think must be a liverwort when I come across it, but it’s not. There was Porpidia albocaerulescens encrusting rocks on the path. Graphis scripta is the elven script lichen, that looks like mysterious little elvish letters on bark. There was even an Usnea, which I didn’t think grew around here.

We didn’t have many entomologists around, alas. The moth people came and identified some seemingly indistinguishable little speckly moths. Maybe they’re pulling my leg? A millipede paid a visit, and was identified remotely by my neighbor Tom Eisner, who has studied the reaction chambers in which this little gal produces hydrogen cyanide for defense (read about it in Tom’s inspiring and autobiographical book For Love of Insects). Andre said the dead ones I found last summer might have suffered from parasitoid attack.

We did pretty well on plants. Through some unspoken consensus, everyone ignored the plants in the cultivated garden, so you will find no daffodils on the list, no azaleas. We did record some other introduced species, like the invasive lesser celandine in the lawn. Charismatic megafauna was detected but not directly observed. Deer damage and deer poop were evident everywhere. A pileated woodpecker was found to have undertaken a woodworking project on the oaky slope, but had missed one of the bugs he was after.

What did we miss? A lot. The buds on trees are now opening, but then were tightly furled–we missed some pretty big and obvious trees. It was a bit chilly and a bit drizzly. We missed the hiding insects and other crawlies that are now out in abundance. The soil had barely warmed from its recent load of snow, so Spring wildflowers (the ones not consumed by deer) were slow to come this year. And we didn’t even try to get bacteria, most microfungi, most algae (we documented some algae indirectly as lichens). The kids did a great job finding little things, including the plastic bugs we hid in the woods for them, and also the invasive flatworms and the sickly deer mouse.

What did we miss? A lot. The buds on trees are now opening, but then were tightly furled–we missed some pretty big and obvious trees. It was a bit chilly and a bit drizzly. We missed the hiding insects and other crawlies that are now out in abundance. The soil had barely warmed from its recent load of snow, so Spring wildflowers (the ones not consumed by deer) were slow to come this year. And we didn’t even try to get bacteria, most microfungi, most algae (we documented some algae indirectly as lichens). The kids did a great job finding little things, including the plastic bugs we hid in the woods for them, and also the invasive flatworms and the sickly deer mouse.

My photos are in my flickr account–you can browse them and quibble with the identifications. About 50 other sites participated in the blogger bioblitz last week, and a quick search of flickr for the tag bloggerbioblitz will find a large gallery of photos from across North America.

My photos are in my flickr account–you can browse them and quibble with the identifications. About 50 other sites participated in the blogger bioblitz last week, and a quick search of flickr for the tag bloggerbioblitz will find a large gallery of photos from across North America.

Our data are being crunched and mapped by the bioblitz crew headed by Jeremy Bruno of The Voltage Gate. He has synthesized the fifty-or-so other blogger bioblitzes that happened during National Wildlife Week. You can browse photos taken by us and other bioblitzers at our flickr pool. Our complete species list can be downloaded as an Excel spreadsheet: Ithaca Bioblitz Inventory.

The Ithaca Bioblitz

We held our first ever Bioblitz on April 28 and it was a lot of fun. You can check out our photos, posted at my Flickr site. We found lots of different things–so many that we’re still tabulating. I’ll get back to you soon with the final species count and THE BIG LIST.

We held our first ever Bioblitz on April 28 and it was a lot of fun. You can check out our photos, posted at my Flickr site. We found lots of different things–so many that we’re still tabulating. I’ll get back to you soon with the final species count and THE BIG LIST.

I have to say, April 28 is a pretty bad time for fungi in upstate New York. Morels aren’t out yet, and what fungi we found were mostly remnants of last Fall’s fruiting bodies, like the empty bird’s nest fungi at right. The only real “fresh” mushroom we found was this LBM (little brown mushroom), Mycena alcalina. Not that I’m any kind of Mycena expert, but when you crush this one, it smells like chlorine.

I have to say, April 28 is a pretty bad time for fungi in upstate New York. Morels aren’t out yet, and what fungi we found were mostly remnants of last Fall’s fruiting bodies, like the empty bird’s nest fungi at right. The only real “fresh” mushroom we found was this LBM (little brown mushroom), Mycena alcalina. Not that I’m any kind of Mycena expert, but when you crush this one, it smells like chlorine.

We found some very interesting organisms. At right is Lophodermium pinastri, a little discomycete that inhabits the needles of pines. It’s related to the tar spot fungi, which you might’ve seen making big black blotches on maple leaves. This one on white pine causes a needle cast disease that can be pretty bad if you’re fond of growing monocultures of pine trees, but on this diverse property it appears to be a low key pathogen. In the photo the black fruiting bodies have not yet split open to release their payload of infective ascospores.

We found some very interesting organisms. At right is Lophodermium pinastri, a little discomycete that inhabits the needles of pines. It’s related to the tar spot fungi, which you might’ve seen making big black blotches on maple leaves. This one on white pine causes a needle cast disease that can be pretty bad if you’re fond of growing monocultures of pine trees, but on this diverse property it appears to be a low key pathogen. In the photo the black fruiting bodies have not yet split open to release their payload of infective ascospores.

Dan over at Migrations came and helped out–you can check out his photos, too. Our greatest contributors were the bryologists, who came and scoured the landscape for itty bitties, then painstakingly identified them all back at Headquarters. More about their finds soon. For now, I’ll leave you with this plucky little guy, the leadback phase of the red-backed salamander–he was just wider than my finger, and man could he wiggle and jump!

Getting ready for the Bioblitz

Tomorrow’s the big day. I’m hosting a Bioblitz on a 5 acre patch of land near Ithaca. A pack of roving naturalists, taxonomists, mycologists, and ilk will join me to inventory all the life forms we can find. I’m excited.

Tomorrow’s the big day. I’m hosting a Bioblitz on a 5 acre patch of land near Ithaca. A pack of roving naturalists, taxonomists, mycologists, and ilk will join me to inventory all the life forms we can find. I’m excited.

And to think that just eleven days ago I was despairing that winter might never end! That’s when a freakish April snow storm dumped almost a foot of snow on me. Three big hunks of trees blocked my driveway, my trees groaned under the weight, and four-wheel-drive was just barely enough to get me to work. The plucky phoebe that had claimed the prime nesting spot above my front deck went ominously quiet.

Three big hunks of trees blocked my driveway, my trees groaned under the weight, and four-wheel-drive was just barely enough to get me to work. The plucky phoebe that had claimed the prime nesting spot above my front deck went ominously quiet.

Now the snow is gone. The phoebe has been joined by his partner, and they have built a mossy nest together atop the downspout. It’s time for our Bioblitz. We’re not the only ones blitzing this week. At least 50 other sites are taking part–they span North America from Canada to Panama. Jeremy Bruno of The Voltage Gate is collating the efforts at his Bioblitz clearinghouse.

Our bioblitz site contains a happy little stream with burbling waterfalls, a hemlock grove, a slope with mature red oaks, and a steep, dry, white pine ridge. We’ll see tomorrow how many different organisms make their homes here, on the land, in the stream, in the air. April is not a great time for fungi in upstate New York (in warmer years we might hope for a morel). So for the next little while, I’ll be blogging about the Bioblitz, and my posts will stray from the fungi we love most dearly.

Want to take a guess at how many species we’ll find? Folks who pitch in tomorrow at the Ithaca Bioblitz can win a prize for the closest guess. For all you folks out there on the internet, mere glory will have to suffice.

« go back — keep looking »