Wild mustard (Brassica kaber) is a weed widespread throughout the United States. It is mainly a summer annual in New York, with smaller populations emerging in the fall. Its seeds can persist in the soil for many years. This weed is common particularly in small grains and fall-seeded forage crops.

Wild mustard is one of 3000+ species in the mustard family. Several mustards species are fall/spring weeds in New York. For help identifying weedy mustards either in the rosette or flowering phase, please visit our mustard identification page.

Identification

Seedlings: Cotyledons are kidney- or heart-shaped and 5mm (1/5”) long by 8mm (3/10”) wide. The cotyledon also has an indentation at the tip. Young leaves (1-2 cm long- up to 4/5”) are oblong, egg- to club-shaped, and alternate with wavy-toothed edges. There are stiff hairs on both leaves and stems.

Mature plant: Flowering stems of the mature plant are upright and branched at the top. The lower portions of the stem have stiff, bristly hairs. The taproot is thin and branched, with fibrous smaller roots.

Leaves: The egg- to oval-shaped leaves are alternate, with scattered stiff, bristly hairs on the upper leaf surface and sunken veins. Lower leaves of the mature plant have longer leaf-stalks (petioles), are prominently lobed, and are often broadest at the tip. Upper leaves are smaller, hairy, have few to no lobes but sometimes toothed edges, and have very short to absent petioles.

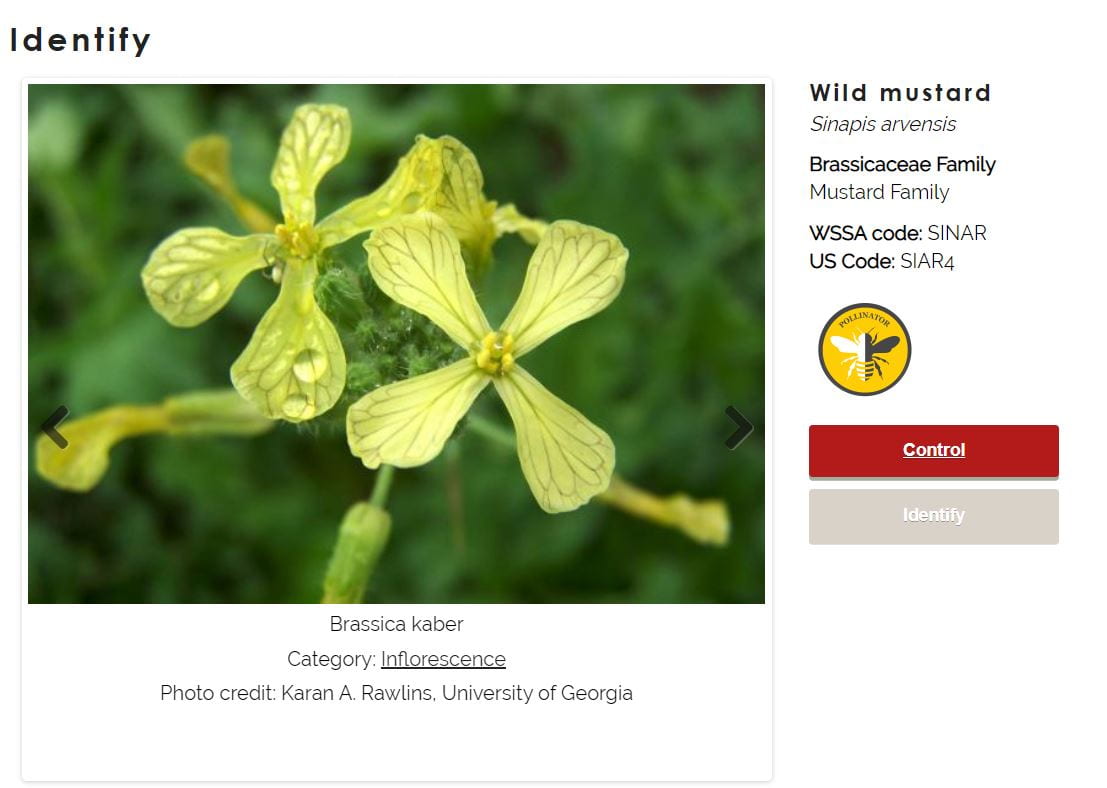

Flowers/Fruit: Flowers appear in clusters (racemes) at the ends of branches. They are approximately 1.5 cm (3/5”) wide, with 4 yellow petals 8-12 mm (up to 1/2”) long. Fruit capsules (siliques) are long and narrow, 2-5 cm (up to 2”) long by 2-3 mm (~1/10”) wide, with a square-sided conical beak approximately half as long as the pod (see photo to right). Seeds are round, smooth, and black or dark purple-brown.

Wild mustard fruits

Photo by Joseph M. DiTomaso via University of California- Davis, Bugwood.org

Management

Chemical control

Wild mustard populations have developed resistance to herbicides in Groups 2 (ALS inhibitors like Raptor and Python), 4 (, synthetic auxins like 2,4 D, dicamba) and 5 (photosystem II inhibitors like atrazine). These have been recorded in several countries, with the most types of resistance found in western Canada. In the US, Group 2 resistance has been found in North Dakota. If you have problems controlling wild mustard consider whether you may be seeing resistance, and whether you have used any equipment recently purchased from the north central states or Canada in that field.

New York specific guidance can be found in the Cornell Crop and Pest Management Guides, or click above for the chemical control of wild mustard from Cornell’s turfgrass and weed weed identification app.

Non-chemical control

Wild mustard establishes quickly and can be very competitive, especially in high nitrogen fields. Emergence peaks in early to mid-spring. Nitrogen causes rapid growth of wild mustard, so in an infested field it helps to avoid over-fertilizing or side-dress later in the season. Shading reduces growth and seed production, so planting competitive crops where in problem fields can reduce weed-crop competition and wild mustard populations the following year. For example, densely planted cereal grains can out-compete wild mustard, as the grains overtop and reduce light for the weed.

In fields where wild mustard is a problem, plant large seeded crops a little deeper than usual and cultivate aggressively before the crop emerges. Throwing soil into the crop row as early as the crop can handle the disruption can bury emerging weed seedlings. You can also consider rotating to a late season crop and cultivating during the spring fallow period to flush and reduce the wild mustard seed bank.

Although there are currently no commercial biological control agents, ground beetles (carabids) do consume Wild Mustard seeds that lie on the soil surface.

References

Uva R H, Neal J C, DiTomaso J M. 1997. Weeds of the Northeast. Book published by Cornell University, Ithaca NY. The go-to for weed ID in the Northeast; look for a new edition sometime in 2019.

Cornell University’s Turfgrass and Landscape Weed ID app. Identification and control options for weeds common to turf, agriculture, and gardens in New York; uses a very simple decision tree to identify your weed.

Many organic management suggestions are from Dr. Charles Mohler of Cornell University. Look for an upcoming book from Dr. Mohler on ecological management of weeds, from Cornell University Press.

International Herbicide-Resistant Weed Database, accessed Sept 2 2020.

I Will Take Action herbicide resistance chart, accessed Sept 2 2020.

Warwick, S. I., Beckie, H. J., Thomas, A. G. and McDonald, T. 2000. The biology of Canadian weeds. Chapter 8: Sinapis arvensis L.

(updated). Can. J. Plant Sci. 80: 939–961.

Profile on Wild Mustard from the Weed Report from Weed Control in Natural Areas in the Western United States. Contains extensive descriptions of chemical and non-chemical control.

University of Michigan Integrated Pest Management wild mustard page. This resource has excellent photos of the cotyledons and bristly stem-hairs of wild mustard.