Redroot Pigweed (Amaranthus retroflexus) is a common, widespread agricultural weed in New York, which is native to North or Central America. Redroot Pigweed is a found in field crops, vegetables, abd small fruit. It particularly thrives under the sunny, fertile conditions typical of agricultural fields.

Toxicity

Amaranthus spp. contains high levels of oxalates and nitrates. Oxalates are absorbed into the gastrointestinal system and bind to calcium in the blood to produce insoluble calcium oxalate that causes kidney tubular nephrosis and eventually, death. If livestock eats large amounts of pigweed, they are likely to be poisoned. Livestock affected by these toxins include pigs, cattle, sheep, goats, and horses. Symptoms indicating poisoning include muscle weakness, abdominal distension (pigs), ataxia, and knuckling at fetlock joints. The high levels of nitrates in Amaranthus spp. can contribute to nitrate toxicity, especially in cattle. Effects of nitrate toxicity on animals include abortions, weakness, accelerated heart rate, rapid breathing, and in severe cases, death. To prevent nitrate poisoning, supplement all cattle with forage that’s low in nitrates, especially those that are pregnant.

Identification

Seedlings: Cotyledons of the redroot pigweed plant are narrow and have a sharp end. They are 10-12 mm (2/5-1/2”) long and dull green to reddish on the upper surface while being bright red underneath. The hairy stems of the seedling are light green and typically red at the base. Young leaves are egg-shaped and alternate. Hair is sparsely present on the leaves’ margins and veins. Upper surface of the blades are green while the lower surface is red. The leaf margins are wavy and the petioles are purplish and hairy.

Redroot Pigweed seedling

photo by Phil Westra via Colorado State University, Bugwood.org

Leaves: Like the leaves of the seedlings, those of the mature plant are alternate with wavy margins. They are ovate or rhombic-ovate. Blades are dull and green above while hairy beneath or at least along the veins. Veins of the leaf lower surface are predominantly white.

Top view of the mature leaves of a redroot pigweed

photo by Robert Videki via Bugwood.org

Mature leaves of a redroot pigweed

photo by Howard F. Schwartz from Colorado State University via Bigwood.org

Mature plant: Stems of the mature plant are stout with a thick and smooth lower part and a hairy, branched upper part. Stems have rough surfaces and can reach up to 2 m (6.5 ft) in height but are usually smaller.

Redroot Pigweed stem

photo by NY State IPM Program at Cornell University via flickr.com

Stem surface of the redroot pigweed

photo by Bruce Ackley from The Ohio State University via Bugwood.org

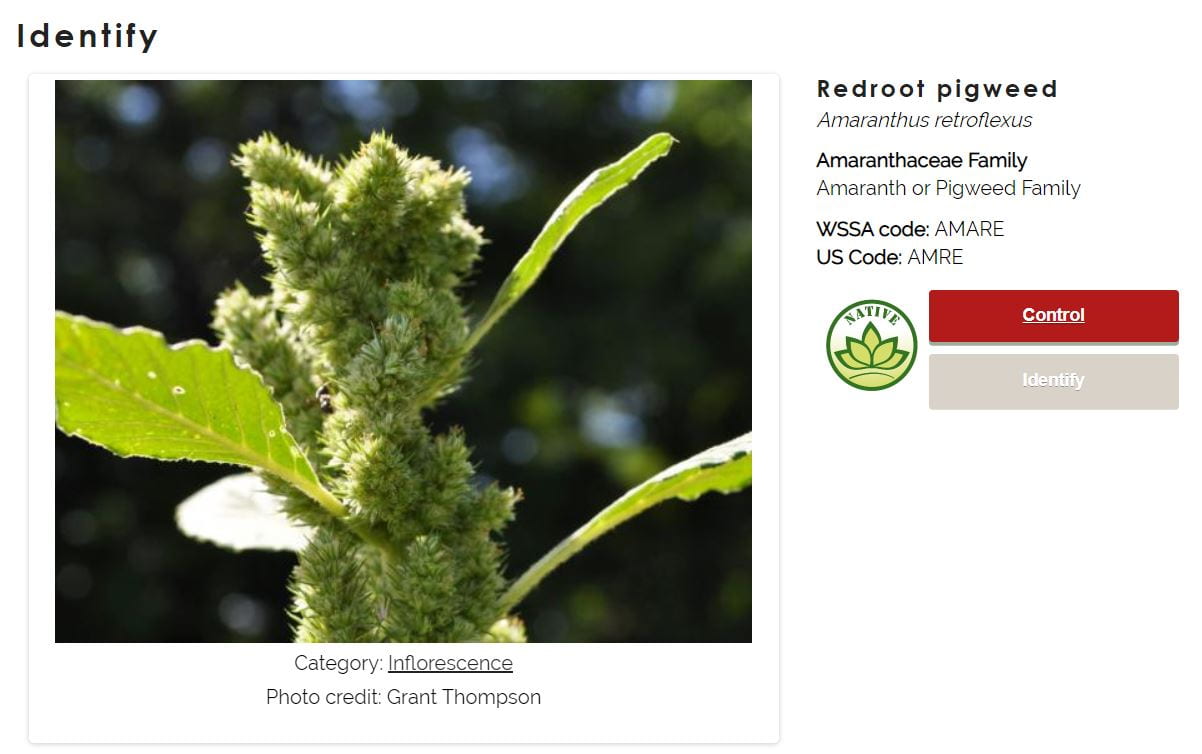

Flowers/Fruits: Flowers are greenish and small. They are produced in dense and stiff terminal panicles (5-20 cm (2-8”) long and 1.5 cm (~3/5”) wide). In the axils of the lower leaves are small clusters of flowers arranged on a branched stem (inflorescences). Male and female flowers are separate and the male flowers fall off soon after the pollen sheds. Fruit (1.5-2 mm (~1/25”) long) are thin-walled and each contain a single shiny black/brown seed.

Mature Redroot Pigweed plant with flowers

photo by Robert Videki via Doronicum Kft., Bugwood.org

Management

Chemical control

Click above for the chemical control of Redroot Pigweed from the Cornell Weed ID site

Non-chemical control

One effective management method is a stale seedbed, including a one- to two-week lag between initial and final seedbed preparation in late spring or summer. The final seedbed preparation must be shallow (no more than 3.8 cm/~1.5″) to avoid pulling fresh seeds up into the germination zone at the soil surface. When the crop is large enough to tolerate inter-row cultivation, slightly hilling before pigweed’s first true leaves emerge will control plants in the crop row.

To maximize the competitive advantage of small grain crops over the weed, it is important to set up a dense, uniform, and healthy stand. Seedlings can be eliminated by harrowing spring grains between the 3-leaf stage and stem elongation. Avoiding excessive fertilization reduces pigweed’s competition with crops. Mulch is an option in vegetable and small fruit; make sure to apply a thick and dense mulch. (For reference, some seedlings may penetrate 3,600 lb/acre of loose straw.)

Pigweed seed density may be reduced by rotating the seed bank with sod crops, bare fallows, and/or integration of a legume crop. Pigweeds are prolific seed producers that cancontinue to form seeds even after mowing or tilling, so it is important to clean up fields soon after harvest and Remove plants that have flowered from the field.

As biological control agents, Pigweed seeds are consumed by various seed predators. The northern field cricket and certain species of ground beetles feed on the seeds lying in the soil surface. Various mammals, including mice, also eat Pigweed seeds.

References

Uva R H, Neal J C, DiTomaso J M. 1997. Weeds of the Northeast. Book published by Cornell University, Ithaca NY. The go-to for weed ID in the Northeast; look for a new edition sometime in 2019.

Cornell University’s Turfgrass and Landscape Weed ID app. Identification and control options for weeds common to turf, agriculture, and gardens in New York; uses a very simple decision tree to identify your weed.

Colorado State University, Guide to Poisonous Plants: amaranth, pig weed

Organic management suggestions are from Dr. Charles Mohler of Cornell University. Look for an upcoming book from Dr. Mohler on ecological management of weeds, from Cornell University Press.

Pigweeds profile webpage from the Michigan State University’s Department of Plant, Soil, and Microbial Sciences.