Dr. Charles “Chuck” Mohler’s book has been released! Read about it in Craig Cramer’s news article on the Cornell Agriculture and Life Sciences website.

Download the book for free from the Sustainable Agriculture Research and Education website.

Dr. Charles “Chuck” Mohler’s book has been released! Read about it in Craig Cramer’s news article on the Cornell Agriculture and Life Sciences website.

Download the book for free from the Sustainable Agriculture Research and Education website.

We received a timely update on potential toxicity concerns with certain forages after frost. For more information, please see Oregon State University’s article or this one from the University of Kentucky.

Thanks to Eric Smith of Cornell’s Central New York Dairy, Livestock & Field Crops team for this information!

A new article by Lynn Sosnoskie of Cornell University was published in the Cornell Extension Field Crop News today.

Clean that second-hand machinery before using! Remember that all equipment can move weeds from one field to another, and plan appropriately.

By: Mike Hunter, CCE-North Country Regional Ag Team

A very popular question has been “What can I spray on my soybeans to control large weeds that weren’t controlled earlier in the season?”. Let me start out by saying that if you have waist high weeds in your soybeans the damage is done and most, if not all, herbicide applications will be a form of “revenge spraying”. Spraying very tall weeds usually provides unsatisfactory weed control. If you still have some weeds that are 6 inches tall or less there is a better chance to control them.

Roundup or glyphosate can be applied through the R2 (full flowering) growth stage on Roundup Ready or glyphosate tolerant soybeans. Enlist One and Enlist Duo can also be applied throughout the R2 growth stage in Enlist or E3 soybeans. Once the soybeans have reached the R3 (beginning pod) growth stage these products are no longer an option.

If the soybeans are at R3 (a pod 3/16” long found at one of the first four uppermost nodes) Cobra, Resource and Basagran are the options that are left. Cobra can be applied through R6 (full seed) or 45 days before harvest, Resource 60 days before harvest and Basagran 30 days before harvest. These are all selective, contact broadleaf herbicides. Unfortunately, none of these are very good at controlling common lambsquarters.

If you have any additional questions about late season soybean weed control, contact your local Cornell Cooperative Extension office.

Cornell University’s Greg Peck and Kate Brown discussed a four-year trial of organic weed management strategies during apple tree establishment with Growing Produce author Thomas Skernivitz. Read about their conversation and research in Growing Produce’s June edition.

Pennsylvania State University’s Dwight Lingenfelter and emeritus professor Bill Curran have published an article on spring weed control in grass hay and pastures. They break down best management practices for winter annuals like mustard weeds and common chickweed (emerge in the fall and flower/set seed in the spring), summer annuals like pigweeds, common lambsquarters, and common ragweed (emerge in the spring and flower/set seed in the late summer or fall), and biennial weeds like common burdock and bull and musk thistle (take two years to complete their life cycle). Check out their advice for the best timing of your spring weed management practices.

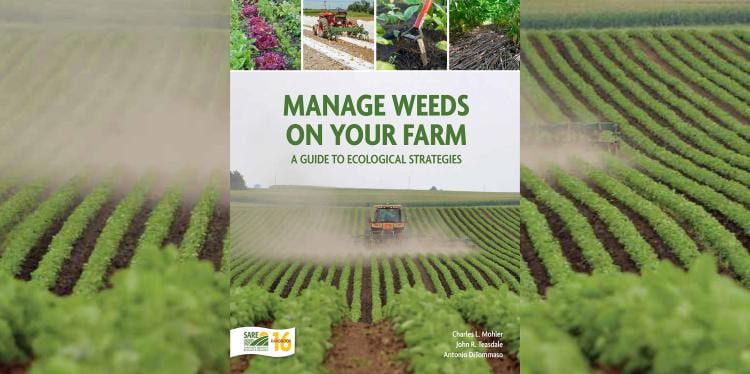

We just received a question from Erie County on this frustrating invasive weed. Here in Ithaca this species is in full flower right now (mid-April 2021), and can be seen carpeting the banks of many streams.

Lesser celandine (Ficaria verna, once Ranunculus ficaria), also known as fig buttercup, is a common woodland, garden, and lawn weed that you may see on your farm or property. It is one of the earlier plants to flower in our area, and is an aggressive spreader. It has a perfect storm of flexible reproduction and vegetative spreading mechanisms; it self-pollinates, reproduces by spreading roots, produces underground tubers that create new plants, and also has aboveground ‘bulbils’ that also start new plants. It’s difficult to remove once established.

Lesser celandine plant. Photo by Caroline Marschner of Cornell University.

Leaves: Lesser celandine leaves are dark green, glossy, shape variable but largely kidney-shaped, with a reptilian-esque pattern on the underside of the leaf.

Mature Plant: The mature plant is low growing and ephemeral, emerging in the early spring, flowering in April in New York, and senescing by early summer. Roots produce tubers that separate easily from the parent plant to form new infestations. The plant also develops aboveground bulbils, which also produce new plants, and seeds from flowers.

Flowers/fruit: Flowers have three sepals below the flower, which helps identify this versus other buttercup species. Fruits are small and innocuous. Bulbils can be seen on the ground after the plants senesce.

Lesser celandine plant. Photo by Caroline Marschner of Cornell University.

Lesser celandine bulbils. Photo by Lelsie J Mehrhoff of the University of Connecticut, via Bugwood.org,

Management: very small infestations of a few plants can be removed by digging up the plants and carefully removing all plant material including bulbils and tubers. Larger infestations are much more difficult to remove. Most authorities recommend treatment with an herbicide after leaves mature but before flowering begins, in early spring. This method is complicated by the plant’s common location near water; make sure any herbicide used is safe for use near water and allowed in your state.

CCE Oneida county has a good description of the species and management suggestions: https://s3.amazonaws.com/assets.cce.cornell.edu/attachments/23004/Greater-and-Lesser-Celandine-2013.pdf .

The New York native plant marsh marigold (Caltha palustris) is another riparian plant with yellow flowers on the same flowering schedule, but it has larger leaves and flowers with five broad petals. Marsh marigold has fibrous roots with no storage structures, and no bulbils forming on the aboveground plant.

CCE Oneida county has a good description of the species and management suggestions: https://s3.amazonaws.com/assets.cce.cornell.edu/attachments/23004/Greater-and-Lesser-Celandine-2013.pdf .

Ohio State University resource for lesser celandine: https://bygl.osu.edu/node/1016

Lesser celandine management from the state of Washington: https://www.nwcb.wa.gov/images/weeds/Lesser-Celandine-Control_Whatcom.pdf

Lesser celandine management from the Little Falls Watershed Alliance outside of DC: https://www.lfwa.org/updates/tips-controlling-lesser-celandine

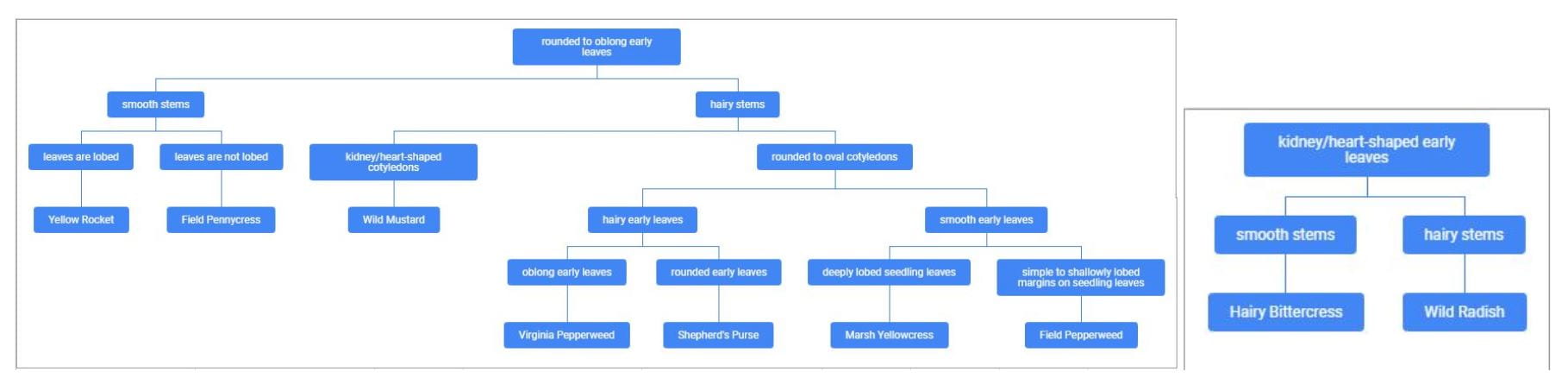

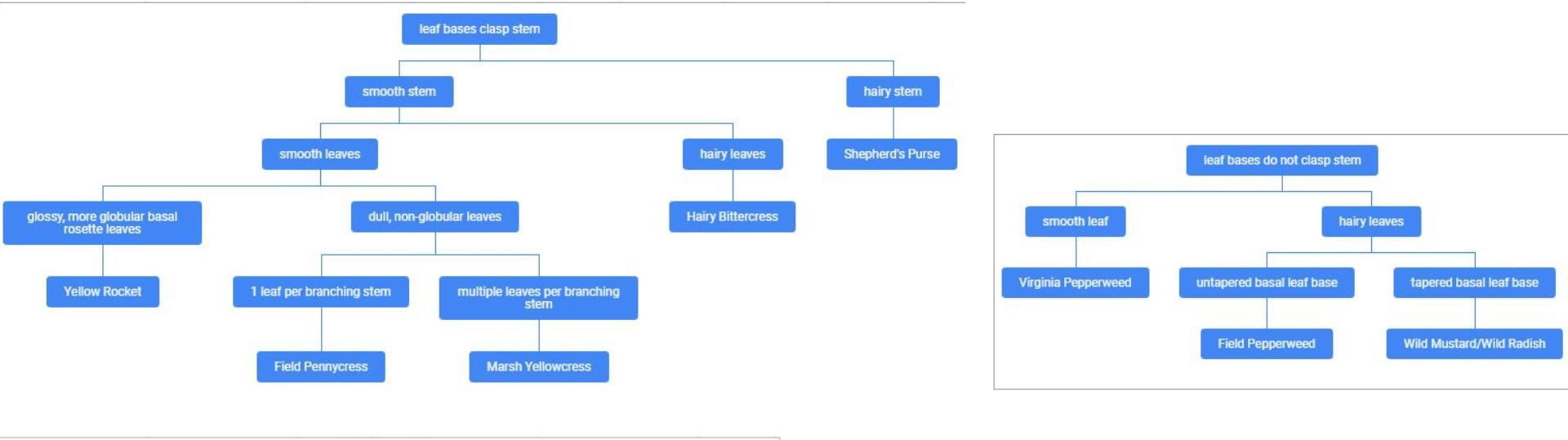

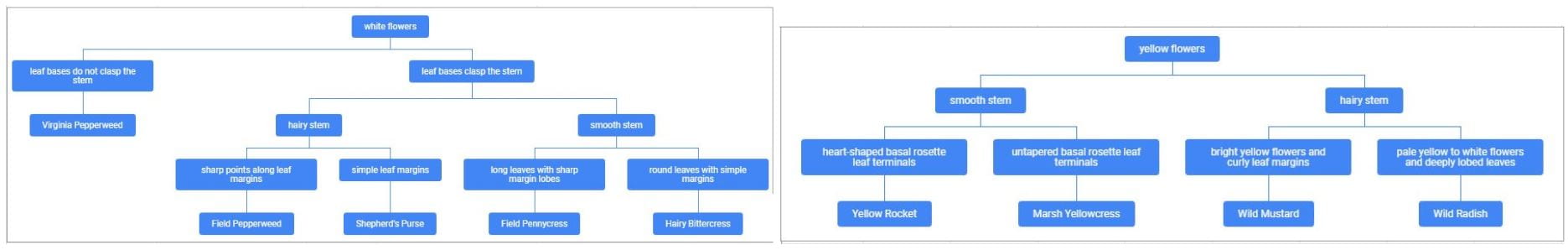

Early plants can be typically be identified according to their cotyledon, first true leaves, and/or the stem.

Uva R H, Neal J C, DiTomaso J M. 1997. Weeds of the Northeast. Book published by Cornell University, Ithaca NY. The go-to for weed ID in the Northeast; look for a new edition sometime in 2019.

Cornell University’s Turfgrass and Landscape Weed ID app. Identification and control options for weeds common to turf, agriculture, and gardens in New York; uses a very simple decision tree to identify your weed.

Spreading dogbane. Photo by Josh Putman of Cornell Cooperative Extension.

Early July, 2020

Josh Putman is Cornell Cooperative Extension’s SWNY Dairy, Livestock & Field Crops representative. He recently ran across this plant in a hay field that had not been worked for a few years. Spreading dogbane, Apocynum androsaemifolium, is in the same family as milkweeds and swallowworts, and the same genus as hemp dogbane. This perennial plant is found in open, dry areas and in disturbed habitats throughout New York and most of the US and Canada.

Leaves: Leaves are oval, 4-6cm (around two inches long), with smooth edges and pinnate veination. They are arranged opposite each other on the branch.

Mature Plant: 0.6m (2 feet) tall, although some sources say 2-5′, with branching reddish stems. Flowers are found at the ends of branches.

Flowers/Fruit: Flowers are bell-shaped with 5 petals that are fused to form the bell and then curl outwards. Flowers can be white as were seen in western NY, but can also be pink or white with pink striping. Fruit are a long, narrow pod up to 11cm (over 4 inches) long; each flower produces two seed pods. Inside the pods are many small seeds with fluffy tufts, much like milkweed or swallowwort seeds.

Toxicity: Dogbanes are reported to be toxic to livestock, containing a compound that interferes with heart function. This toxicity persists when the plant is dried as well as when fresh. There is no specific information on the toxicity of this species to livestock.

Management: Management information for this species in agricultural settings is sparse; most resources discussed it in the context of a native wildflower/shrub. In blueberry fields, nicosulfuron mixed with surfactant suppressed spreading dogbane (>60%), and dicamba spot sprays were over 80% effective. Glyphosate spot sprays worked better than hand pulling, and wiping with glyphosate was also effective (Wu and Boyd, 2012). In an early experiment from the 1940s, dogbane was partially susceptible to 2,4 D (Egler 1947). In a forest setting, aerial application of glyphosate did not control spreading dogbane (Pitt et al 2000).

References

New York Flora Atlas: http://newyork.plantatlas.usf.edu/Plant.aspx?id=123

Native Plant Trust’s Go Botany online plant key: https://gobotany.nativeplanttrust.org/species/apocynum/androsaemifolium/?pile=non-alternate-remaining-non-monocots

USDA Plants Database: spreading dogbane page. https://plants.usda.gov/core/profile?symbol=APAN2.

University of Maryland Extension Toxic Plant Profile: Milkweed and Dogbane: https://extension.umd.edu/learn/toxic-plant-profile-milkweed-and-dogbane

Ohio State University Perennial and Biennial Weed Guide: Hemp Dogbane. https://www.oardc.ohio-state.edu/weedguide/single_weed.php?id=40

Fire Effects Information Systems entry for spreading dogbane: https://www.fs.fed.us/database/feis/plants/forb/apoand/all.html#125 .

Lin Wu and Nathan S. Boyd. 2012. Management of Spreading Dogbane (Apocynum androsaemifolium) in Wild Blueberry Fields. Weed Technology 26(4)777-782.

Frank E. Egler. 1947. 2,4-D Effects in Connecticut Vegetation, Ecology 29(3)382-386.

Frank E. Egler. 1949. Herbicide Effects in Connecticut Vegetation, Ecology 30(2)113-270.

Douglas G. Pitt et al. 2000. Five Years of Vegetation Succession Following Vegetation Management Treatments in a Jack Pine Ecosystem. Northern Journal of Applied Forestry 17(3) 100–109.

Mid-June 2020

CCE Field Crops Specialist Mike Stanyard ran across this weed in winter triticale. It appeared to have been seeded with the triticale, as it was only growing in the row, as tall as the heading out triticale. Scott Morris of the Cornell Weed Ecology and Management lab identified it as common corncockle (Agrostemma githago), a common weed seed contaminant in grain crops. Identifying traits include narrow, opposite leaves with long hairs, and single, purple five-petaled flowers which bloom at the top of a long stalk over the summer. Common corncockle is mildly toxic to humans and livestock when ingested.

This was historically a significant weed of European grain crops, but largely disappeared from its native range due to the advent of herbicides, improvements to seed cleaning technology, and the shift to winter wheat. Herbicide resistance to 2,4-D and MCPA is mentioned in an article from the 1980s on corn cockle competition from eastern Oregon, but the species is not listed in the International Database of Herbicide Resistant Weeds maintained by the Weed Science Society of America. It is listed as a noxious weed in Arkansas and as a plant pest in South Carolina. Common corncockle is also used as a garden plant.

References:

Bugwood.org’s listing for corn cockle: https://www.invasive.org/browse/subinfo.cfm?sub=5049

Wikipedia entry for corn cockle (also corn-cockle, corncockle): https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Agrostemma_githago

WSSA International Herbicide-Resistant Weed Database: http://www.weedscience.org/Pages/Species.aspx

Rycrych, DJ 1981. Corn Cockle (Agrostemma githago) competition in winter wheat (Triticum aestivum). Weed Science 29(3) pp. 360-363.

North Carolina Extension Gardener Plant Toolbox: Agrostemma githago: https://plants.ces.ncsu.edu/plants/agrostemma-githago/

USDA PLANTS Database file for common corncockle: https://plants.usda.gov/core/profile?symbol=AGGI