Imagine walking into an art gallery with a group of people, perhaps your classmates or colleagues. You’re holding two slips of paper. One says “love,” the other, “hate.” Your only instructions are to walk around the gallery, and place “love” under a work of art that moves or speaks to you, and place “hate” under a work that puts you off, or even repulses you.

There’s nothing you need to know beforehand, about art, or artists or history. You don’t need to have a strong grasp of concept or design or intention. You just have to respond to two different artworks, based only and entirely on your reaction to them.

After everyone in the group has placed their pieces of paper somewhere in the gallery, they walk from piece to piece and talk about their responses – what pulled someone in or pushed them away, and why.

This activity, known as a token response, is one of many creative entry points for developing skills in close observation and description, visual analysis, empathy, knowledge of cultural and historical contexts, and communication. It’s also an activity that Alison Rittershaus, the Lynch Postdoctoral Associate in Curricular Engagement at the Herbert F. Johnson Museum of Art, deploys regularly with groups that visit the museum, where it functions as an invitation, a way for students to realize they don’t need to be experts or bring a sense of context or history with them to experience a work of art. They just have to bring themselves.

The Power of an Emotional Response

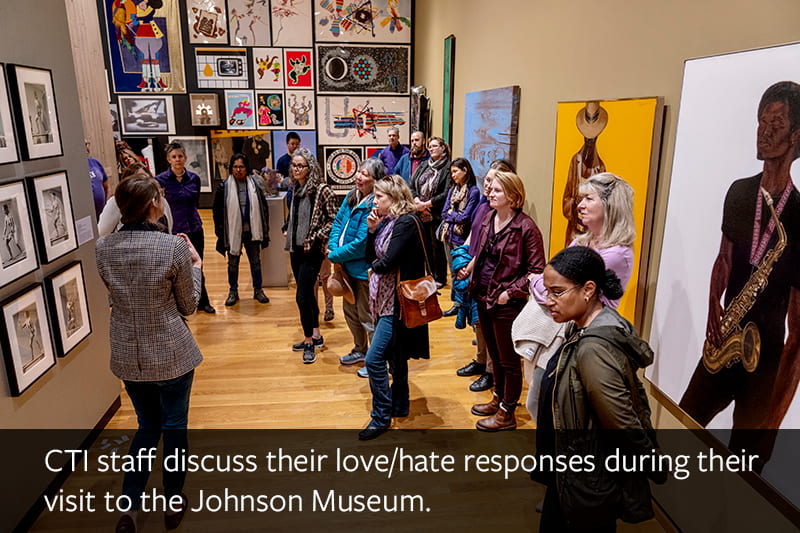

In October, the CTI had the chance to participate in the token response activity when we visited the Johnson Museum of Art to learn about the museum’s pedagogical offerings for a variety of courses across disciplines. It was just one way in which we experienced a taste of the museum’s ability to engage students and faculty, regardless of their prior knowledge or experience of the arts.

After we placed our slips of paper on the ground in front of an artwork that we loved and one that we hated in the museum’s Richard F. Tucker ’50 and Genevieve M. Tucker Gallery. Rittershaus brought us together as a group, and chose a few of the artworks to discuss why the works provoked the emotions and responses they did. A few pieces were both loved and hated, which provided an avenue for particularly rich discussion – an image of a woman giving birth to a manifesto was loved for its provocation and ideas, but the unsettling aesthetics prevented others from looking more closely at the piece and artist’’s statement, creating questions and discussion about the ways in which art is created and communicated.

One of the reasons we found this activity particularly fruitful is that it makes the museum feel approachable to everyone – it’s not just for people with a deep knowledge of visual culture, but, instead everyone’s emotional reactions are valued, and thoughtful and engaging conversations can arise naturally from a space of curiosity and instinctive response. It also creates a safe space to practice thoughtful discussion in the face of disagreement.

One of the reasons we found this activity particularly fruitful is that it makes the museum feel approachable to everyone.

But the token response activity is just one example. As Rittershaus led our CTI group through the galleries and teaching spaces, she highlighted different ways that learning experiences can be designed in the museum in cooperation with Cornell faculty.

Pedagogical Possibilities

Getting out of the classroom can help to create especially strong memories of learning, partly because people tend to remember novelty. If you think back on your own education, learning experiences outside of the classroom may stand out in your memory as well. Museum visits can also nurture a sense of community among the students especially if activities are structured to provide opportunities for them to share ideas about the artwork they are seeing.

Although we often think of museums as hosting classes in art history or archaeology, the Johnson Museum education specialists work with classes from many different fields including STEM and social sciences. Close observation, consideration of perspectives and cultural context, and communication skills are essential to many disciplines.

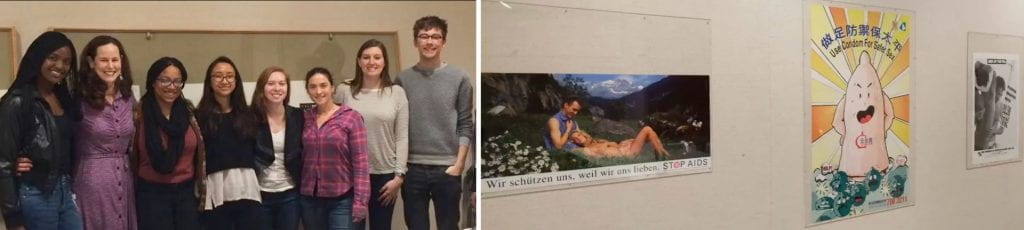

For example, Jeanne Moseley, an associate professor of practice from the Department of Public & Ecosystem Health in the College of Veterinary Medicine, invites students to utilize the arts to grapple with the complexity of global health issues and challenges, as well as examine historical and current strategies for communicating about public health issues across diverse cultural contexts.

She worked with Rittershaus to organize interactive study gallery sessions for students, featuring the photography of Brian Weil, an artist and activist, who fought to make AIDS a subject of cultural and political discourse. Alongside Weil’s photos are HIV/AIDS education posters, providing a geographical and historical overview of how culture and politics structure public health communications.

The key in the above example, as with all courses, is thoughtful planning and coordination. Instructors do need to help students connect the museum experience with their course-specific learning so that it is more than just a fun field trip, and the Johnson Museum offers several avenues to do so. These options depend on an instructor’s planned learning outcomes for the students in their course; the assignments they want to design; and the ways in which they’d like to engage with the museum.

For example, instructors who’d like to provide an experience for a class in real time can choose to work with a staff member from the museum to help design a class session either in the galleries or within one of the classrooms. Or, instructors can choose a more independent approach, and lead the class activities themselves. Another option is the Richard Sukenik ‘59 gallery, which functions as a teaching gallery space for classes that would like to engage with art over multiple visits or to complete longer assignments.

Note that the Johnson Museum does require advance notice of two weeks for class visits, to ensure that they can prepare any necessary materials, including artifacts, and facilitate a positive and productive experience. The Johnson Museum can also pull works from storage, with two weeks notice, for students to visit individually or in small groups to work on papers and projects.

In other cases, instructors can design assignments in which students visit the museum by themselves or in small groups to work on a project. These assignments may range from asking students to do visual analysis, research, or even creative writing.

Suggestions for activities, close observation, writing prompts can be found on the Johnson Museum website. The museum also provides more structured materials, such as worksheets to guide students through visual analysis.

Some of the activity prompts that stand out include asking students to generate a list of ten questions about a piece in the museum, writing a review of an exhibit considering what is being communicated through the curatorial choices, or writing a story or a poem based on an artwork. Other classes might ask students to identify an object that they see as relating to a theme of the course and explain or write about how they see the relationship.

The Johnson Museum offers a plethora of additional resources and thrives on cross-campus connection. The museum’s colleagues are happy to work with instructors to brainstorm ideas to meet learning objectives for those who may be unsure what is possible, and to work with faculty with specific plans to help bring their lessons to life. All that’s required is an open mind, a sense of possibility, and some advance notice.