You land on the moon.

The stars glitter above you; familiar constellations etch themselves across the night sky. But here, now, in this headset, the night sky is outer space, in all its strange magnificence. The night sky, outer space, is all around you.

And… there are dinosaurs in it. There’s definitely a polar bear. And an enormous blue whale, all made of stars.

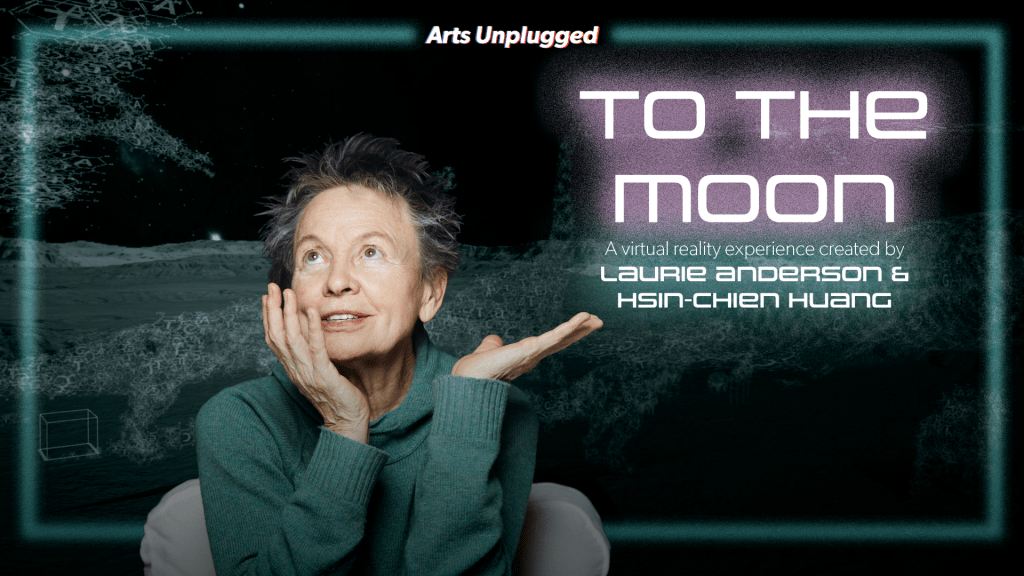

When I heard that To the Moon was coming to CTI as part of Laurie Anderson’s upcoming Arts Unplugged visit to Cornell, I was eager to experience it, without entirely knowing what to expect.

You see, I’m one of CTI’s more troglodyte-inclined colleagues. My only VR experience prior to attending To the Moon was a Christmas adventure at a friend’s house, where her boys excitedly showed me how I could visit Machu Picchu, Antarctica, and the Mesozoic era, all from the safety of their kitchen. Which was cool. No doubt about it, it was very cool. Like, I didn’t feel threatened, exactly, by the experience of seeing a 3D-animated T-Rex pass right by me, but the virtual reality experience managed to be impressive enough – and altered my blood pressure enough – to concern the family’s goldendoodle, who chose that particular moment to march over and plant himself protectively in my lap.

Beyond that one-off adventure, it wasn’t until I started working at CTI last November that I first considered the possibilities for VR in the classroom as an educational tool. A professor in Romance Studies, where I previously worked, had once offhand pondered the possibilities of using VR to allow her students to visit Paris and see the locations of the books they read and history they discussed. The idea intrigued me, but at the time seemed more futuristic than probable.

Then I learned how VR technology is allowing Cornell students to train to prepare a sample for cryo-electron microscopy, where specimens are frozen at approximately -180 degrees Celsius. It’s a multi-step, precise process typically only available to advanced scholars, because of the risks of harm to the experiment, expensive equipment, or even the scientists themselves.

I learned how, through a 2023-2024 Innovation Grant, VR is allowing music students to practice conducting a full orchestra. And then I learned about Laurie Anderson’s To the Moon.

In some ways – ways that you will have to attend to see for yourself – the exhibit baffled my expectations. The rendering of outer space, its stars and galaxies, is flooring. Unexpected dinosaurs aside, the scope of the rendering, with its constellations and foggy Milky Way, was my favorite part.

Because of my limited experience with VR, I was less adept with the controllers than I would have liked. Had I navigated a bit closer to those giant dinosaurs, those extinct manifestations of my childhood imagination, I perhaps would have realized that what I thought were stars was actually DNA – and that you can actually wander into a dinosaur, or the blue whale, and the music will slightly change, personalizing and altering your experience.

The debris field and surrealistic aspects were impressive and the exhibit does have a strong perspective on humanity’s impact on, well, pretty much everything it touches. I hesitate to further describe this in detail – in many ways it’s best experienced, unspoiled, for oneself. That said, To the Moon is a unique vision with statements it wants to make, with nods toward humanity’s dependence on fossil fuels; competition in exploration and for resources; and above all, our profound capacity for waste. These images are provocative, and open doors to further thinking and discussion with one’s students, and oneself.

Aesthetically, the exhibit is gorgeous, rendered in spectacular black and white. It’s very hard not to be enraptured with the technology. True, there are some things that VR will never replicate – at least not to my knowledge. Nor should it. When I virtually traveled to Machu Picchu, my lungs did not feel how thin the air can be when you’re high in the Andes, nor what scent it carries. I also couldn’t reach out and pet the llama – but then again, perhaps that’s for the best.

But in Laurie Anderson’s To the Moon, you absolutely will feel like you’re in outer space, and you won’t have to worry about your oxygen supply.

And overall, the experience inspires. It immediately peppered my imagination with more possibilities for the technology. In my past academic life, before the long odds of the academic job market sent me in another direction, I taught a variety of Shakespeare classes. Now, when I consider the possibilities of VR, I wonder: could students one day tour early modern London, and inhabit, to a degree, the world that Shakespeare and his contemporaries knew?

I’m also intrigued by what this technology could mean for access, once it becomes more affordable. Could VR allow students to stand among the groundlings at the Globe theatre – minus the experience of a live audience, of course, but even so – to experience a play as Early Modern Londoners would have? Of course, you can have that experience now at the reconstruction of the Globe Theatre in London – if you can afford the flight, the hotel and the ticket.

But as VR technology becomes more ubiquitous, and less expensive, what could this mean for student access to experiences like this? A class of students, off to see As You Like It in Elizabethan London, without ever leaving the room?

And what of history, or language learning?

Imagine a classroom full of students able to virtually explore Machu Picchu, as a component of their Spanish or Latin American history classes.

I’m clearly less well-versed in STEM, but consider this: a group of students walking on a melting glacier, an unstable surface too dangerous to otherwise access, yet still seeing nearly firsthand the impact of climate change? The garbage and debris scattered along the trails leading to Mount Everest’s summit?

Or just imagine those students who are now learning how to prepare samples for cryo-electron microscopy – a process as strange to me, a tech-skeptical humanist, as the prospect of visiting the stars. Imagine students summoning a full orchestra to life, conjuring a symphony with a wave of their hands.

Reality in the virtual world is about perception, as it is, in many ways, in our daily lives. There are some things the virtual world cannot replicate. Scent. Touch. I do not know if that will change, but again, as a slight troglodyte, I find that aspect hard to imagine. And frankly, as that slightly alarmed humanist, I also find my inability to conceive of that possibility reassuring.

Still, when I look at the possibilities for technology in the classroom, and particularly in the humanities, my academic home, I wonder if this is what it felt like in the 1960s, during the space race. After all, I have, in my way, been to the stars.

What else is possible?