Last week, I attended the Dairy Cattle Welfare Symposium, which aims to bring together “dairy farmers, veterinarians, consultants, universities, and the dairy community to discuss best recommended practices with focus on animal well-being, management, husbandry, animal-people interaction, health, and productivity.”

One of the main topics for the symposium was Group Housing of Dairy Calves, with Dr. Emily Miller-Cushon from the University of Florida and Dr. Joao Costa from the University of Florida presenting on their research in this area. Following their presentation, a panel of producers from different areas in the US talked about their transition to group housing calves – and not all of them utilized barns!

Miller-Cushon and Costa presented background data from NAHMS to start: a survey of producers showed that the overwhelmingly majority (85.3%) raise calves in individual housing until weaning. While this is the norm in many occasions, what does research say about the implications on animal welfare of group-housed calves?

The presenters discussed how calf housing affects two different categories of calf welfare:

- Basic health and functioning

- Natural behavior and affective state

Basic health and functioning can be easily monitored by measuring growth rates, feed intake and health. But how can natural behaviors be monitored? Answering this question was a motivation for the researchers to study group housed calves in comparison to individually housed calves. Surprisingly, different outcomes in both categories of health and natural behavior were seen in these comparisons.

In every study Miller-Cushon and Joao covered, group housing or pair housing showed a benefit or no difference in measurement for average daily gain, solid feed intake and final body weight. In fact, most calves that were paired up in housing early in life had greater solid feed intake when compared to individually housed calves, or calves paired up later in life, both in total pounds of intake as well as a percent of body weight.

The research clearly shows that increased social contact positively affects feeding behavior. Calves experience social learning and will increase feed intake prior to weaning because of this social facilitation.

In health categories, eight studies compared group house calves versus individually housed calves, tracking total diseased incidence, mortality and number of treatments being observed for both. Some studies showed an increase in total disease incidence and mortality for group house calves, while other studies showed no effect of group housing on these health outcomes. Management factors that reduce disease risk, especially in group housing situations, include: all-in-all-out systems, maintenance and cleaning of auto-feeders, dry bedding, reducing group size, and increasing space allowance.

The effects of social housing on behavior have been studies across many species, and it is known that early social isolation is detrimental on social development as well as cognitive development. These can include learning difficulties, abnormal repetitive and social behavior and a higher fear response.

In terms of dairy calves, we observe with individually housed calves that they have a lower ranking in the herd, reduced success when faced with competition, increased aggressiveness and less ability to interact with animals they don’t know, and reduced amount of play behaviors. With group-housed calves, calves seek out to touch other calves and actually prefer to feed next to another calf, as well as showing less fear to novel situations when raised in a group-housed situation.

Studies evaluated calf fear responses to a test of a new situation. Calves that were individually housed showed more fear – more vocalizations, defecation, and increased heart rate – than those calves that were group housed from birth. In other words, those calves that were group housed were better equipped to cope with stressful situations, whether it be a new calf, a new pen or new feed. Calves individually housed from birth showed a greater aversion to try new feeds presented to them, and ate a lesser amount of that new feed than their group-housed comparison.

In terms of cognition and learning and relearning new things, again group-housed calves had an advantage. A study in 2015 utilized a screen that calves would push with their nose to receive milk. Once they were taught to push the screen, a white screen would mean “push and receive milk”. A red screen would mean “push and receive no milk – aka don’t push”. Calves that were group housed learned this set of rules fairly quickly; calves individually housed struggled. After this portion of the study, the screen were reversed – red for milk, white for no reward. Group housed calves again were able to figure out the change and received milk. Individually housed calves struggled even harder with this, with the majority of calves never figuring out how to consistently receive milk after the switch.

So why does this matter? Is cognitive ability and behavioral flexibility even important? In the first two years of life, think of how many changes we throw at our heifers. Think of how stressful these events can be – changes in pen mates, diet changes, the transition to becoming a lactating cow, being milked for the first time, finding water, and avoiding boss cows. All of these instances are opportunities for her to learn and adjust. If we equip her as a calf to learn novel ways of approaching a situation and reduce the amount of fear she has, her stress level comes down and her growth and production can increase.

“But,” you say, “I raise my calves in hutches for a reason! I don’t like sick calves!” Even pair housing calves in hutches has benefits over individual housing, and may decrease incidence of disease because of the benefits that social learning brings. And by pair housing, I don’t mean putting two calves in one hutch with one wire frame.

During the panel talk, three different producers discussed their ways of group or pair housing. One of these panelists, Gerardo Gonzalez Castaneda, showed pictures and dimensions of how he utilizes a pair of hutches for two calves, initially with 24 square feet of play area utilizing the wire mesh panels, and later expanding to 112 square feet outside each hutch pair.

Benefits he listed for pair raising calves included better socialization (less time vocalizing when moved to a new pen), better transition from liquid to dry feed, increased rate of daily gain, more playing, and calmer calves at weaning. He also noted that about 95% of the time, calves slept in the same hutch!

The pair housing strategy also utilizes divisions for individual spots for drinking to avoid competition if one calf drinks more slowly. Challenges they encountered included sucking on each other, which was overcome by feeding more milk and the competition during feeding, overcome by the divisions. If by chance, one calf in the pair gets sick, they still keep the calves together and code the healthy one as BOS (Buddy of Sick).

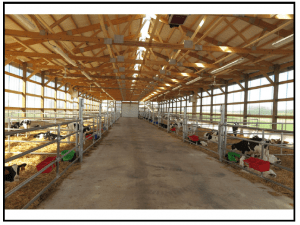

Another panelist, Pam Selz-Pralle of Selz-Pralle Dairy in Wisonsin, describes their mob-feeding group pen strategy. Pen sizing on this dairy also increased from 35 to 45 square feet per calf, with each pen holding four heifers. The sizing of these pens is also preferred to be deeper rather than wider, and utilizes a mesh barrier for sides rather than open bars. A headlock is included in each pen for one-on-one care if needed. Ventilation is achieved through positive pressure, and the barn has full air exchange every six minutes.

After group housing, calf mortality at Selz-Pralle Dairy dropped to half of one percent, treatment rate is less than 1%, and average daily gain is 2 lb/day through weaning. After weaning, gains reach 2.5 lb/day to three months of age. The cost per pound of average daily gain also decreased from $2.14 to $1.16, with less bedding per animal required and more efficient labor.

Group housing, when managed correctly, can yield some huge cost savings as well as improve social and cognitive abilities in those calves; the benefits can last through her whole lifetime. Implementing some sort of group or pair housing strategy as early as possible in a calf’s life should be looked at to see where or how it makes the most sense. Every farm is different – calling in your extension educator, veterinarian or nutritionist to help decide how to develop and implement a strategy is a great first step.