I’ve had plenty of opportunity in my work to watch other graziers, as well as graze my own animals. One conclusion I’ve come up with is that anyone can graze in a wet year; it takes a good grazier to graze in a dry year. Drought disrupts grazing operations more than confinement operations, since confinement operations plan to have stored feed for their animals. When drought weather hits, confinement operations have time to react and make alternative plans. It doesn’t affect their livestock. As pasture soil dries, grass growth slows, graziers try to keep their rotation going hoping for rain. When it doesn’t come, they must change to stored feed, which can have a negative effect on livestock production.

An Ounce of Prevention

Some of the management practices that can help prevent drought disruption are:

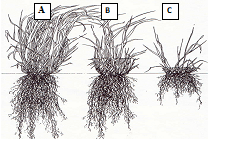

1. Graze Half and Leave Half – This refers to managing your residency of animals in the paddock. You should have an estimate of the dry matter before your animals enter a paddock, then remove the animals when half the dry matter is grazed. This practice is depicted in the drawing below with (A) being the sward when animals enter, (B) when animals should be removed, and (C) if overgrazing is allowed. The practice increases productivity in normal weather, but protects from future droughts in the following ways:

- Leaving more residue sward above ground leaves longer roots below ground so they can reach more water.

- The increased residuals also shade the soil so that evaporation is reduced.

- More leaves increase solar collection to get the plants off to a quicker start.

2. Soil Organic Matter and Droughts – When I first started grazing in the 1980’s, we were told to follow the New Zealand style of grazing ryegrass, which was to put animals in when grass was ten inches and remove them at three inches. This provided very high protein and low fiber forage for the grazing animal. Since then, our graziers have evolved to a Northeastern style of grazing, which is closer to putting the animals in around fifteen inches or more and remove when half is consumed. This fits our climate and native grasses better since the New Zealand style was found to reduce the amount of soil organic matter (SOM). The lower fiber in the plants decreased the carbon content of the residue, as well as in the manure from animals eating it. Forty percent of SOM is carbon. The shorter residue will also be more prone to droughts. Graziers should monitor their organic matter in their soil for the following reasons:

- For every one percent increase in SOM, an acre of pasture will hold 16,000 gallons of water per acre. If you can raise SOM by two percent, it will hold more than an inch of rain than it did previously.

- For every one percent increase of SOM, the soil will have 20-30 lbs. more nitrogen, 4-5 lbs. of phosphorous and one lb. of sulfur.

Can Irrigation be a Tool for Drought Relief?

Over the years, I have heard many experiences and have read a few studies about using irrigation on pastures. The experiences and studies both show that more often than not, irrigation doesn’t work well. These are the questions a grazier needs to answer to see if irrigation can work for them:

- Do you have access to the volume of water you need? Optimum pasture sward can be produced with one inch of water (27,000 gallons per acre) every week. Obviously, it gets by with much less. For my example lets irrigate a half of an inch a week (13,750 gallons). With a forty-acre pasture system, this would require 540,000 gallons per week.

- Do you need legal permission to use this much water? As I understand DEC rules, they allow taking up to 100,000 gallons per day from surface water.

- Do you have the infrastructure to move the water around your pastures? This is where the math gets complicated. It involves what type of sprinkler system you’ll be using. For example, the K-Line system (photo 1) handles low volume for smaller areas, like 8 acres in seven days. It requires a flow rate of 40 GPM at 50 PSI at the pump discharge: Sizing a pump to this depends on size of your water lines, how many sprinklers, and the amount of head or elevation the water needs to travel up or down.

- If you move up to the water reel system (photo 2) for larger pastures these requirements go up to: 75-150 GPM at 70-120 PSI.

On-Farm Example

The most sustainable pasture irrigation system I’ve had the opportunity to visit was on Birds All Dairy in Canaseraga NY. Janice Brown and her husband Kim Shaklee have operated the 40 cow grazing dairy since 1993. Kim was an irrigation manager for a number of farms in Colorado before they moved here to New York. When they came the resources they specifically looked for was: reasonably priced and a farm that had irrigation potential. His design consists of:

- A pond supplied by a stream acts as his reliable source of surface water for the system. In dry times the rate of flow isn’t high enough to supply the 80,000 gallons a day the small Kifco hard hose traveler can apply.

- He uses an electric pump to pump out of the wetland at night (lower electric rates) up to a holding pond 130 feet above the wetland.

- He has six inch lines connecting the wetland and holding pond. The same line feed from the pond to valves in the different pastures.

- From these valves he connects a booster pump that adds to the gravity from the uphill ponds to provide the flow required for the water reel.