To fulfill the public trust, wildlife management needs to address the full range of social values relative to wildlife, changes in land use, and changing ecological conditions. 1

Current wildlife management practices often involve inconsistent or inadequate consideration of all beneficiaries’ interests. For example, stakeholder engagement may give disproportionate consideration to some public interests and values for historic and pragmatic reasons. 2 Catering to a narrow range of interests (such as hunting or trapping) implies that wildlife management as a whole is based on a user-pay, user-benefit system instead of a truly public trust resource approach to administration that is sensitive and responsive to broad and diverse public interests. 3 4 5 6 Public trust thinking 7 has arguably always been applied in wildlife conservation and governance in the U.S.; however, even though trust administrators are legally obliged to implement these ideas, 8 they often fail to do so comprehensively or consistently. 9

Attempts to incorporate broader interests and values into public wildlife conservation can also be inhibited by narrow definitions of wildlife, limited ability to influence wildlife conservation on private lands, uncertainty about who is responsible for wildlife trust administration, and lack of clear metrics on how well the public trust in wildlife is being managed. 10

Many citizens might be unaware that they have rights and responsibilities as wildlife trust beneficiaries. Misalignment of public wildlife agency actions and public trust thinking reduces agencies’ relevancy and legitimacy and increases conflicts among beneficiaries, ultimately compromising trust administrators’ ability to conserve wildlife. 11 12 Given the current challenges to managing wildlife for diverse constituents, finer attention on integrating universal ideas of public trust thinking and good governance is needed.

Wildlife governance principles based on public trust thinking and good governance norms 13 14 can guide public wildlife agencies and their partners towards fairer, more responsive and more relevant governance behaviors and management practices. Widespread adoption of wildlife governance principles promises a more cohesive and informed system that can elevate the importance of wildlife management among all beneficiaries and better respond to contemporary conservation challenges 15 16

Back to the Public Trust Anthology main page

Featured Publications

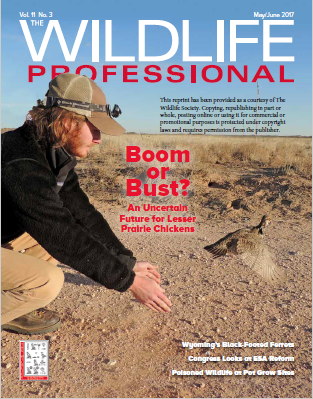

Click on the image to be directed to the article website. Placing your cursor on the text will automatically stop the movement.

- Governance Principles for Wildlife Conservation in the 21st Century ↩

- Applying Public Trust Thinking to Wildlife Governance in the United States: Challenges and Solutions ↩

- Applying Public Trust Thinking to Wildlife Governance in the United States: Challenges and Solutions ↩

- Stakeholder Engagement in Wildlife Management: Does the Public Trust Imply Limits? ↩

- Stakeholders as Beneficiaries of Wildlife Management ↩

- A Conservation Institution for the 21st Century: Implications for State Wildlife Agencies ↩

- Principles of Public Trust Thinking ↩

- Applying Public Trust Thinking to Wildlife Governance in the United States: Challenges and Solutions ↩

- Governance Principles for Wildlife Conservation in the 21st Century ↩

- Applying Public Trust Thinking to Wildlife Governance in the United States: Challenges and Solutions ↩

- Not Only for the Money: Why More Citizens Should Have a Voice in State Agency Decisions ↩

- Governance Principles for Wildlife Conservation in the 21st Century ↩

- Governance Principles for Wildlife Conservation in the 21st Century ↩

- What Does it Mean to Manage Wildlife as if Public Trust Really Matters? ↩

- Developing Governance Principles for Public Natural Resources ↩

- Not Only for the Money: Why More Citizens Should Have a Voice in State Agency Decisions ↩