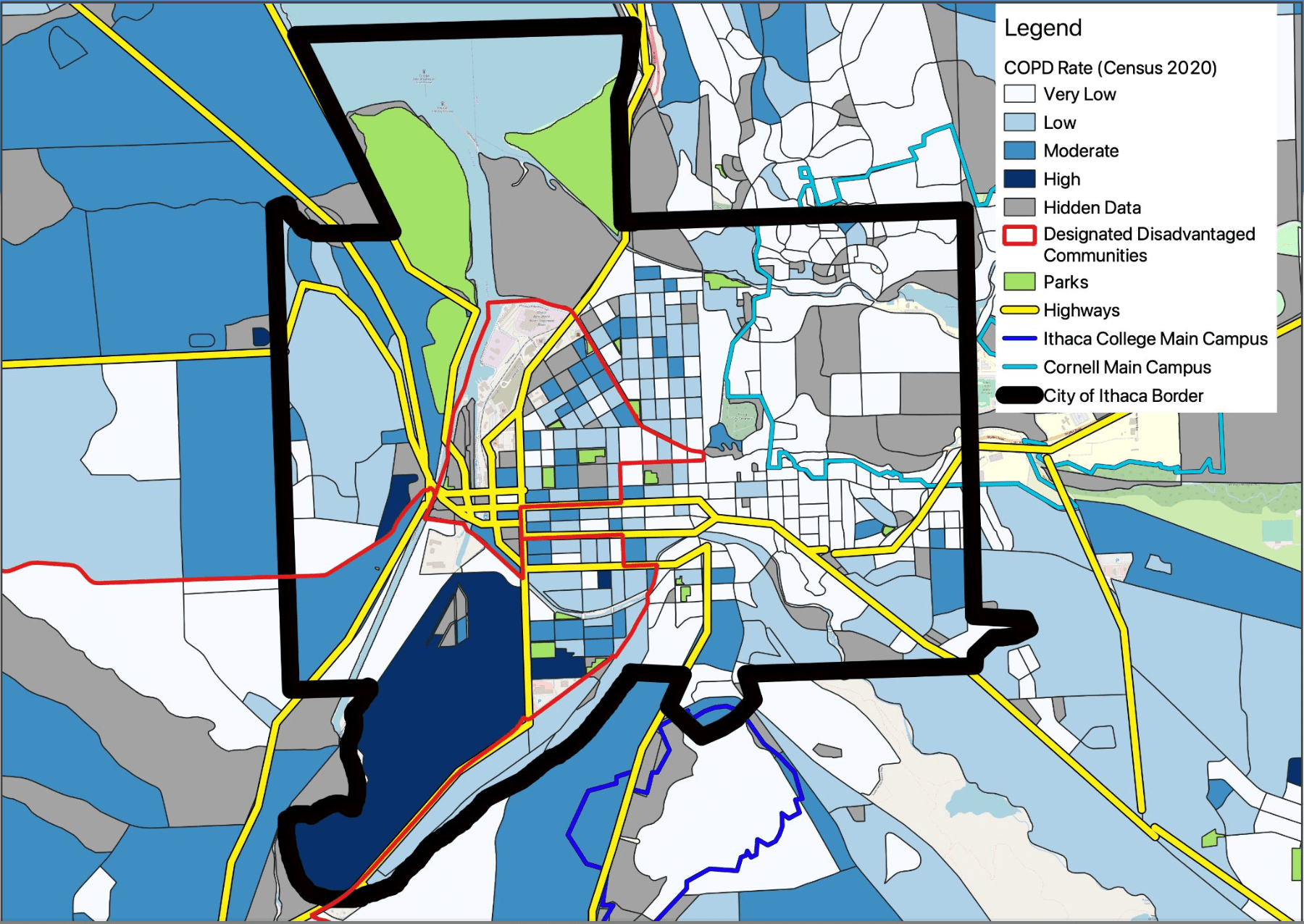

Mapping health data to inform policy

The Ithaca Green New Deal was adopted as a resolution in June 2019, committing the city to carbon neutrality across the community by 2030. Almost half of the city’s emissions are transportation related. “Transportation is a hard nut to crack,” notes Rebecca Evans, Director of Sustainability with the City of Ithaca, largely due to Ithaca’s hilly landscape and short-term populations.

The Ithaca Green New Deal was adopted as a resolution in June 2019, committing the city to carbon neutrality across the community by 2030. Almost half of the city’s emissions are transportation related. “Transportation is a hard nut to crack,” notes Rebecca Evans, Director of Sustainability with the City of Ithaca, largely due to Ithaca’s hilly landscape and short-term populations.

At an Ithaca Green New Deal steering committee meeting, Cornell Public Health’s Director Dr. Alex Travis approached Evans about a new collaboration between the City of Ithaca, Cornell Public Health, and Cayuga Health Partners (CHP)—an integrated network of over 40 primary and specialty clinical practices in the region.

“I immediately recognized this partnership as an opportunity for storytelling,” says Evans, since it can be difficult to communicate the importance of addressing transportation in policy when long-term effects of climate change seem distant to some residents and policymakers. Quickly, the plan took shape as a geospatial analysis project, using CHP’s clinical data to visualize how populations experience health problems that can result from air pollution, or be worsened by it.

“As clinical providers, we have vast amounts of data, but we’re not necessarily thinking about all the ways it could be used to inform policy decisions,” says Amy Carver, Assistant Vice President of Clinical Integration and Population Health with CHP. “In this case,” says Carver, “we provided data on chronic conditions that relate to breathing problems,” such as asthma or chronic obstructive pulmonary disease (COPD).

When geospatial analyst and Cornell Public Health Assistant Professor of Practice Dr. Alistair Hayden received CHP’s data, he began working with MPH students to aggregate the data. “Our goal was to protect patients’ privacy, while depicting where people experience health conditions that relate to air quality in as much detail as possible,” he says. He teaches students the value of contributing to ethical, data-informed decision making. “These kinds of partnerships are great opportunities for students to work with the types of agencies they might work with in the future.”

As Director of Sustainability for the City, Evans sees combining health data with claims about transportation emissions as an opportunity for the City to secure resources for disadvantaged communities. “The data we found didn’t surprise us,” she says, since the highest concentrations of asthma and COPD were found in areas considered high-risk on climate justice maps, including areas with higher concentrations of unhoused populations, lower-income households, and populations of color.

Competitive federal funding is available for transportation-related climate work, but when the City first tried to translate state and federal definitions of disadvantaged communities, “most of Ithaca was off the map, and many populations were falling through the cracks,” notes Evans. For her, translating clinical health data to maps that visualize the story of air quality-linked health outcomes is a communication strategy, as much as a tool for evidence-informed policy.

“I’m thrilled we can leverage our clinical data in a meaningful way to support the community,” adds Carver. From the City’s perspective, Evans sees the next steps as “digging deeper to identify and address other health conditions linked to air quality.” Installing air sensors, conducting interviews with residents, and integrating indoor air quality data through home energy assessments, are some of the strategies she’s considering. “This study was just the first step,” she says, “and a great starting point towards asking more of the right questions about transportation.”

Written by Audrey Baker

Map of COPD-Prevalence Rates Across the City of Ithaca