Expanding Horizons Journal: Lauren Johnson

My name is Lauren Johnson, and I am a member of the Cornell University College of Veterinary Medicine class of 2020.

After finishing my first year of vet school at the end of May, I packed my bags, boarded a plane, and flew more than 5,000 miles over 12 hours to the South American country of Chile. Thanks to the support of Cornell’s Expanding Horizons program, I am spending my summer here working with dairy cows and Chilean veterinarians. Before attending Cornell, I never had the opportunity to work with dairy cattle, but greatly enjoyed learning about them through my classes and through my job as a student milker at the Teaching Dairy Barn. I wanted to travel to Chile this summer to expand my knowledge of dairy production, learn about veterinary medicine in another country, and improve my Spanish skills.

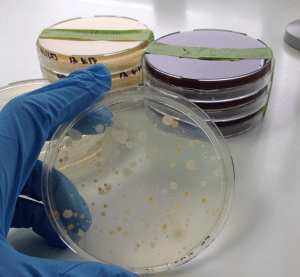

My base for these ten weeks is the University of Concepción’s campus in Chillán, Chile. Located four hours south of Santiago by car, Chillán is a small city where the towering, snow-capped Andes are a constant fixture on the horizon. My hosts, Dr. Alejandra Latorre and Dr. Marcos Muñoz, are Chilean veterinarians and professors at the university- both completed PhDs at Cornell. With their help, I am researching milk quality at local dairy farms by determining what types of bacteria are present in milk samples I collect from the farm. The results may alert the farmer to the presence of mammary gland infections in the cows or identify a particular area of farm management that needs to be improved.

Milk quality is important from a public health standpoint, especially since there are still Chileans who drink raw milk (most often on dairy farms). This is despite the fact that the pasteurization of milk for human consumption has been compulsory in Chile since 1931. Even when milk is pasteurized to prevent bacteria from causing illness, increased bacteria content decreases shelf life and promotes the development of off-flavors.

While the direct link between cow and consumer may be the most obvious connection between human and animal health, Dr. Muñoz pointed out another one to me on a recent farm visit. Ensuring the comfort and health of the workers at the dairy is crucial to improving cow welfare; happier workers will treat cows more carefully and kindly. For example, Dr. Muñoz recommended that a farm install rubber flooring mats over the concrete floor in the milking parlor. This simple change makes standing for long hours more comfortable and keeps the milker’s feet warmer. As I continue my work here, I look forward to learning more details like this that are applicable to farms anywhere in the world.