Haiti, Hurricanes and Cholera: a One Health Approach

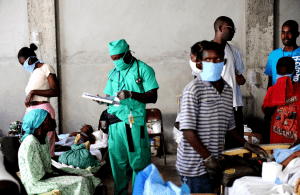

Hurricane Matthew struck Haiti on October 4, 2016 and has acted as a deadly catalyst upon the country’s worsening cholera epidemic. The outbreak began in 2010 after the catastrophic earthquake, when contaminated waste from a United Nations peacekeeping base entered a nearby river. In order to understand this epidemic from a comprehensive One Health perspective, it is important to understand both the biology of the disease and the role of public health and safety planning in limiting its spread.

Hurricane Matthew struck Haiti on October 4, 2016 and has acted as a deadly catalyst upon the country’s worsening cholera epidemic. The outbreak began in 2010 after the catastrophic earthquake, when contaminated waste from a United Nations peacekeeping base entered a nearby river. In order to understand this epidemic from a comprehensive One Health perspective, it is important to understand both the biology of the disease and the role of public health and safety planning in limiting its spread.

Cholera is a diarrheal disease caused by the bacteria Vibrio cholerae. The bacteria typically are found in estuaries and brackish water and when ingested, can cause rapid, severe dehydration that can be fatal if not treated. The disease spreads quickly when drinking water becomes contaminated, as often occurs in cases of natural disasters that damage water and sanitation infrastructure. In addition, disease transmission often increases in rainy seasons when flooding leads to contamination of drinking water. In Haiti, Hurricane Matthew caused massive flooding and damage to clean water supplies and sanitation in an area that had already lost approximately 10,000 lives to cholera since the start of the epidemic six years ago, and 28,500 cases had already been diagnosed this year alone.

If the dehydration is treated with fluid support, recovery from the disease typically progresses well and antibiotic therapy is not required. However, villagers in Haiti often have to travel miles on foot to reach treatment centers or hospitals that are running with limited resources and personnel. Prophylactic antibiotic use is not recommended for either clinically healthy visitors from cholera-prone areas or for individuals who are at risk of the disease, even in crisis situations. Dr. Tobias Dörr, assistant professor in Cornell’s Weill Institute for Cell and Molecular Biology, uses Vibrio cholerae as a model bacteria in his search to discover new antibiotics. In his research, he has uncovered the bacteria’s unique ability to resist a common class of antibiotics. Instead of dying when exposed to the antibiotic, the bacteria forms a sphere shape and can then recover its normal shape and begin multiplying again when the antibiotic is washed away. According to Dörr, the current strain of Vibrio in Haiti is already resistant to another class of commonly used antibiotics, and although it is still susceptible to many others, prophylactic antibiotic use could create a dangerously resistant strain of the bacteria.

Preventative measures center around water sanitation and maintaining clean drinking water. Vaccines for cholera do exist, but offer incomplete protection that lasts for only three months and typically requires a two dose series with at least a week between doses. Despite these challenges, there is some utility to using them in cases where a cholera outbreak is predicted. To this effect, the World Health Organization has sent 1 million doses of the vaccine to Haiti.

From a biological stand point, cholera spreads rapidly if there are no proper preventative measures in place and can be fatal if untreated. From a public health stand point, cholera must be attacked from three different directions – the creation of a water sanitation system, education of the people to recognize the early signs of cholera and try to seek treatment early, and support in terms of both staff and equipment to cholera treatment centers. Moreover, it is clear that in the globalized world we currently live in, greater care needs to be taken to ensure that foreign bacteria are not introduced into an area that is naïve to them, which requires an additional level of environmental planning and consideration that is best supported by evaluating the situation from a One Health perspective.

This article was written by Nikhita Parandekar De Bernardis, DVM (CVM Class of 2015), International Programs and Special Projects Coordinator at the College of Veterinary Medicine.