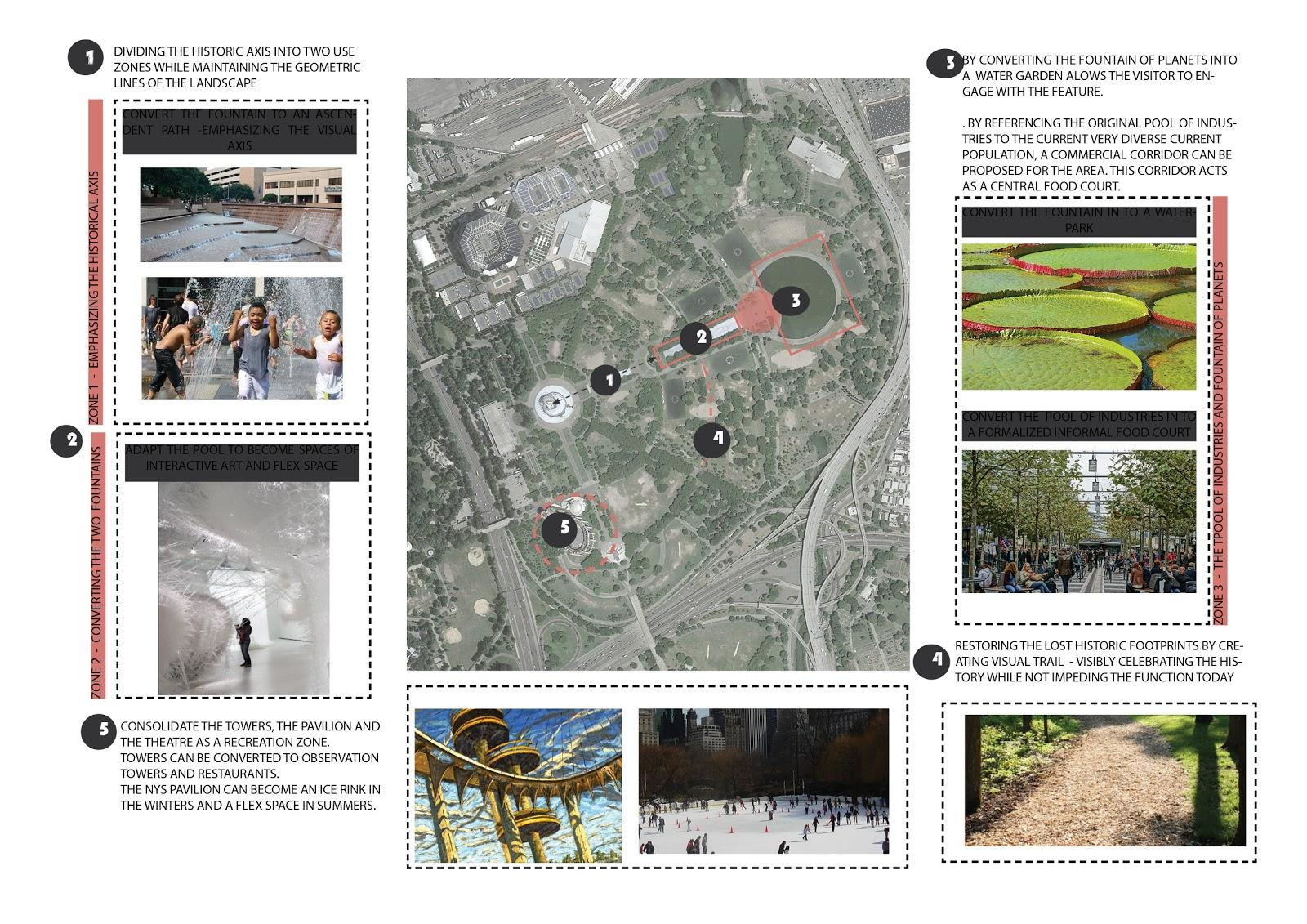

Our design interventions address the three focus sites previously mentioned: the pathway system in the historic core, the fountains and surrounding areas in the historic core, and the New York State Pavilion. In addressing the adaptive reuse potential of the historic core and Pavilion area, we considered five sub-zones: Sub-zone 1, the axis running from the Unisphere to the Rocket Thrower, including the Pool of Reflections; Sub-zone 2, the Fountains of the Fairs; Sub-zone 3, the Court of the Universe and other paved areas around the Fountain of the Planets; Sub-zone 4, the Fountain of the Planets; Sub-zone 5, the New York State Pavilion..

Fountains

The Pool of Reflections, Fountains of the Fairs, Fountain of the Planets, and their surrounding areas provide great potential for adaptive reuse in the historic core. These fountains were the largest fountains in the world when they were constructed, however most of them are no longer functional, and often sit collecting leaves and garbage.[1] It is unlikely that the fountains will be used for their original purpose, due to concerns over operating expenses, restoration expenses for structures that are no longer functional, safety concerns with the public entering the fountains, and health code regulations over the use of water.[2]

The fountains pose an opportunity to not simply restore the features to what they were, but make them more functional for current users while preserving their historic integrity. In considering adaptive reuse options, we looked at the many informal ways these spaces are currently used. Many park users play soccer in the Fountains of the Fairs, as the structures are bounded and the balls do not leave the space.[3] When the Unisphere fountain is turned on, park visitors use it to cool off; while this poses safety concerns, it also indicates that a structure that engages park users would likely be successful. In adapting these spaces, we sought to pay homage to the history of this area while creating an inviting, fun, and interactive space for the community.

To reactivate this area of the park and acknowledge the site’s history while creating active spaces, we propose the following for Sub-zones 1-4:

Sub-zone 1: Pool of Reflections

This first sub-zone directs park visitors up to the Unisphere; the reflecting pool currently in this path would be fitted with a stair/fountain feature so that users can enter the space and move up to the Unisphere along the center of the axis. The water feature would pay tribute to the fountain’s past use, while emphasizing the visual axis up to the Unisphere. This adaptation recognizes the clear desire of park users for a water feature as seen in the numbers of visitors that enter the Unisphere fountain when it is turned on.

Possible Design for the Fountain. Sourec of Photos: Fountain Steps: “Fountain steps, Bristol” by mira66. Licensed under CC BY-NC-SA 2.0 via Flickr – https://www.flickr.com/photos/21804434@N02/8412907493.

Sub-zone 2: Fountains of the Fairs

The fountains in Sub-zone 2 can be converted into interactive public art space, transforming this area into an active, people-oriented space, without losing the historical fountain structures. The Fountains of the Fairs will become spaces for park users to gather and play, and areas for community artists to display their work. Curating these interactive art pieces could be done by a central community-based organization—or a rotating group of organizations—allowing the art to be representative of its setting in Queens, and an opportunity to showcase local work. The art pieces could be permanent or rotate on a shorter-term basis.

Art Ex. #1: Hot Rod. Source: Greg Wass, Chicago, 2014 , Hot Rod (Orly Genger, 2013) https://www.flickr.com/photos/gregorywass/1390699318

Art Ex. #2: Restless Rainbow. Source: Greg Wass, Chicago, 2014 , Hot Rod (Orly Genger, 2013) https://www.flickr.com/photos/gregorywass/1390699318

Art Ex. #3:Pinakothek der Moderne. Source: Martin Müller ; The third space ‘ Pinakothek der Moderne, Modern art museum, Munich https://www.flickr.com/photos/martin2012/2589982779 [4]

Sub-Zone 3: Court of the Universe

Sub-zone 3, the plaza area surrounding the Fountain of the Planets, can be used as a market space. During the 1964 Fair, this area was a space to showcase industry and manufacturing; now it is something of a “dead space,” that’s not fully utilized.

Most large gatherings take place elsewhere in the park.[5] By creating a flexible space for food vendors, markets, and other events, the space will feel less expansive and more welcoming. The new market space would be a draw for the many park-goers playing soccer and other activities in the area. It would also become an area that people stop at, rather than a thruway as they travel elsewhere in the park. There is currently an issue with illegal food vendors in the park, who are often close to the bleachers and sports areas in order sell to a captive audience.[6] This market area recognizes the desire for food availability in the park, while also understanding the need for formal systems of regulation. This market space will provide what park users want, in a system that park management can work with.

Sub-zone 4: Fountain of the Planets

The Fountain of the Planets should be converted into a water garden, changing this area from an inactive space to a destination within the park. In addition to the water garden, the fountain feature should be restored or replaced with a similar feature, and docks and sitting areas added around the inside edge of the fountain so that park visitors can walk around, sit, and experience the space to its fullest potential. The water in the Fountain may present a challenge to this plan; although the fountain is a distinct structure, the water connects to the Flushing River and Flushing Creek. Because of this, the water is brackish, which is a challenge, but not a barrier to creating a water garden. There are not many plants that can tolerate water with high saline content, limiting the options available to create a water garden.[7] Another option is to place floating planters in the fountain, bypassing the constraints of the water type.

Fountain Utsubo-Park1. Source: Fountain Utsubo-Park1″ by MASA Licensed under CC BY-SA 3.0 via Wikimedia Commons – http://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/File:Fountain_Utsubo-Park1.jpg#mediaviewer/File:Fountain_Utsubo-Park1.jpg[8]

Fountain Steps, Bristol. Source: Fountain Steps: “Fountain steps, Bristol” by mira66. Licensed under CC BY-NC-SA 2.0 via Flickr – https://www.flickr.com/photos/21804434@N02/8412907493

If the brackish water creates a significant obstacle, the fountain restoration and addition of seating can still be undertaken to create a more people-friendly space in this sub-zone.

Sub-zone 5: Pavilion

The New York State Pavilion was designed by Philip Johnson, and listed on the National Register of Historic Places in 2009.[9] However, the site is currently empty and inactive. This area, encompassing the three observation towers and the Tent of Tomorrow, and located adjacent to the Queen’s Theater (what during the Fair was Theaterama), holds great potential for adaptive reuse.

Reuse of this site is a major priority for both the park and the community. People for the Pavilion, a non-profit advocacy organization dedicated to raising awareness about the structure, is currently working on community outreach and other strategies to develop plans for the Pavilion. While this initiative is still underway, common preliminary ideas focus on creating a community space that speaks to the diversity of the area; this includes art spaces, cultural spaces, and programmable public space uses.[10]

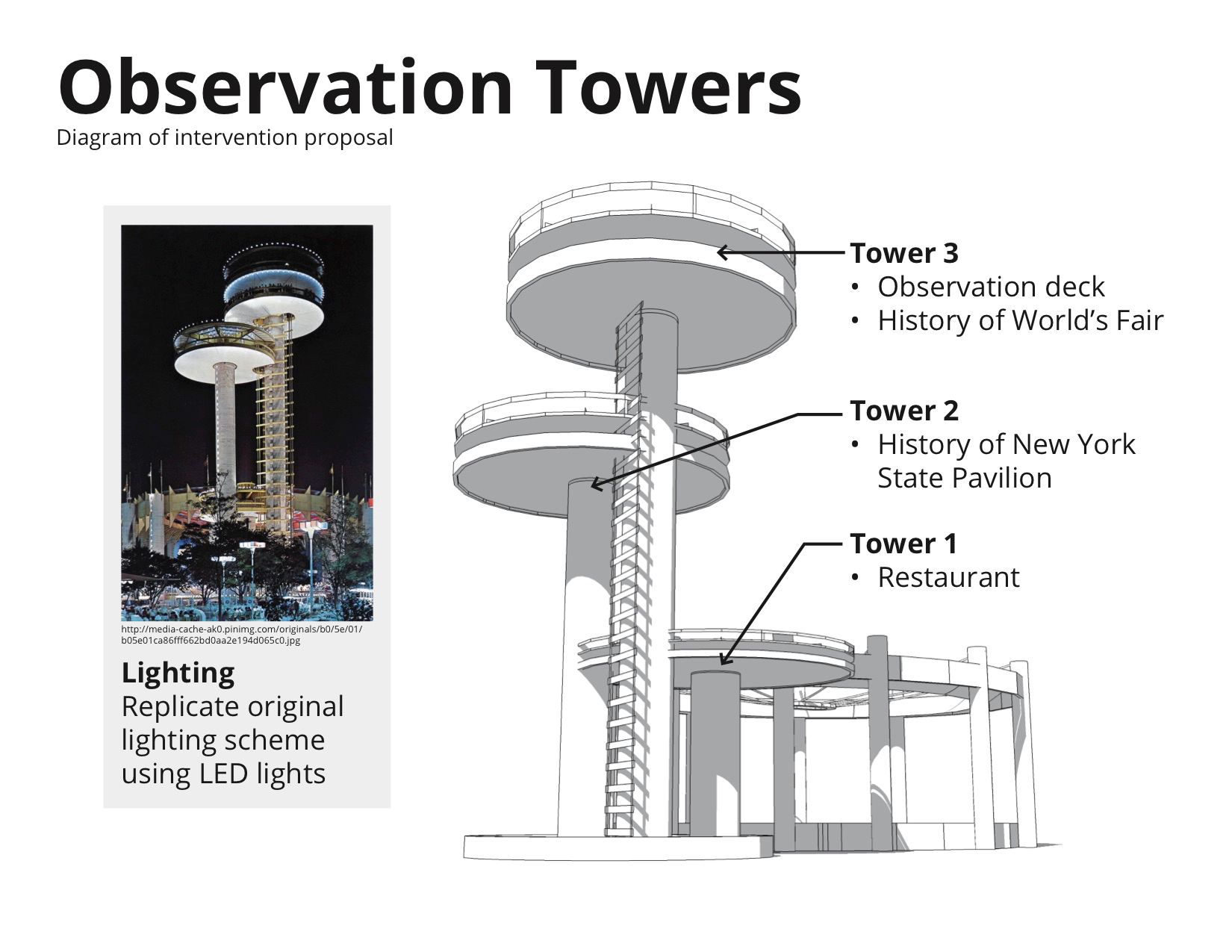

In recognition of the priorities already identified, the work already being done, and understanding the historical value of these structures, we propose adaptive reuse strategies to make the Observation Towers and the Tent of Tomorrow functional, welcoming features of the park. This involves consolidating the towers, tents, and theater as a unified sub-zone, creating a sense of purpose and activity in the area, and drawing users into this part of the park.

Observation Towers: For the three observation towers, we propose two uses. One tower, as suggested in the Strategic Framework Plan, should be converted into a restaurant.[11] This will attract people from outside the area as well as those who already frequent the park, and contribute to the space identity we propose for this sub-zone. The two remaining towers should be restored as observation towers, with a historical and educational component. Information can be presented on the history of World’s Fairs, the New York State Pavilion, and Queens today; this is an opportunity to recognize the past, present, and future of this area. In 1939 and 1964 the World came to Queens, but today, as the most diverse place in New York City, Queens is a reflection of the world. From the observation towers visitors will learn about Queens and the diverse groups residing there, with maps and visual cues for what they are seeing all around them. We propose a pricing system for the observation tower similar to the Queens Museum, where residents of the park’s surrounding communities can access it for free.

A preservation concern in this area is lighting the towers. Historically, the towers were lit with blue, custom-made globes; to recreate these would be expensive and the lights would be fragile. The public has indicated a desire for lighting to be restored to the towers, however, there is an opportunity to take advantage of new technology, echoing the lighting of the past while using more sustainable and efficient lights.[12] We recommend lighting the towers in the same style (size and placement) as the original lights, but with LED technology that is more energy-efficient, and can also be programmed for different colors, times, and other features. The lighting of the towers should complement the Unisphere lighting, as well as our proposed lighting of the trees along the historic pathways.

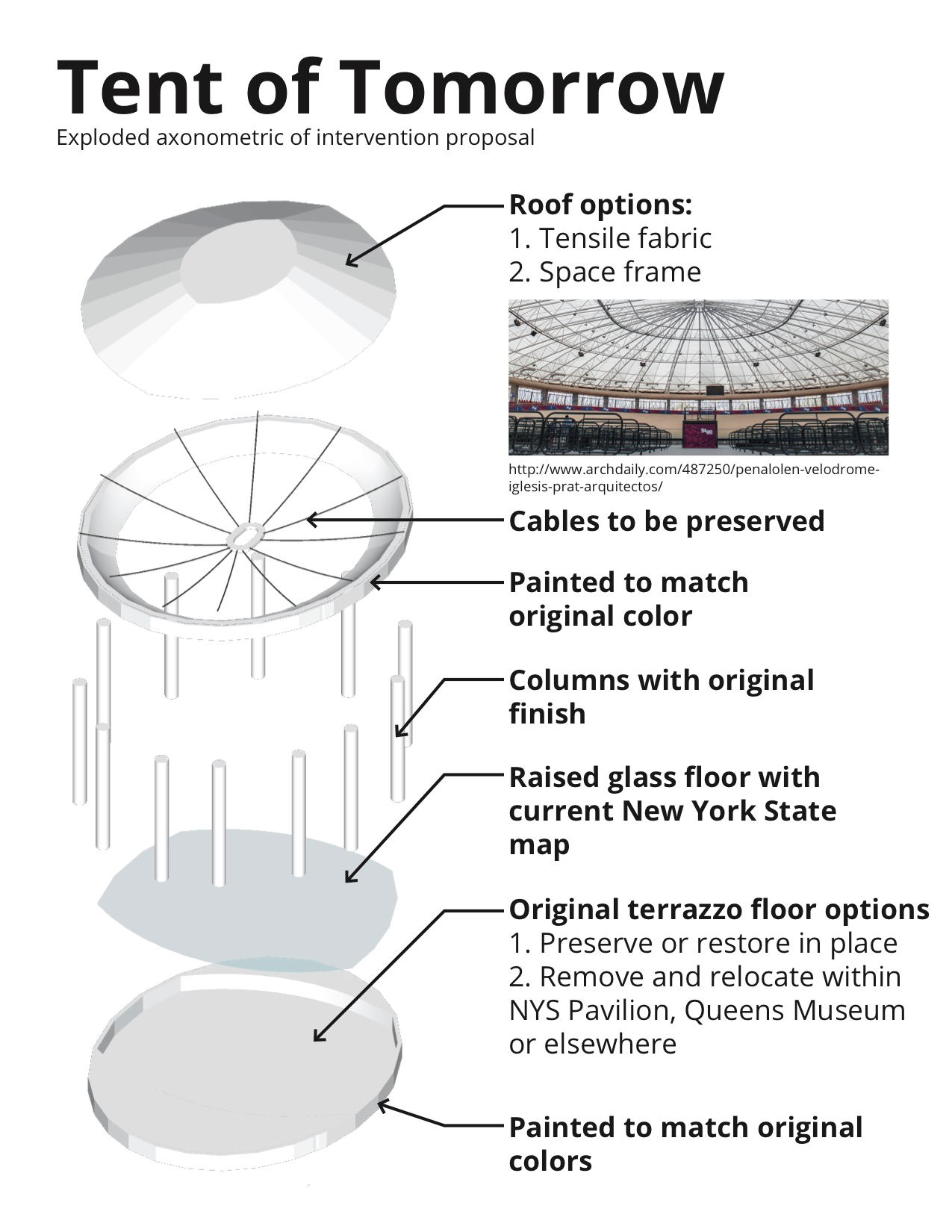

Tent of Tomorrow: The Tent of Tomorrow presents both the greatest challenges and the greatest opportunities for adaptive reuse on this site. This structure was the main pavilion for New York State during the 1964 Fair; while it was originally designed as a temporary structure, additional funds were put into its construction as it was being built to make it permanent. The structure has gone through a number of post-fair uses, including as a rock venue in the 1960s and a roller rink in the 1970s. The Tent of Tomorrow has been vacant for some time now, and the biggest challenge to adaptation is the tens of millions of dollars that it will take to make substantial change.[13]

In addition to the financial challenges, there are a number of preservation concerns relating to the structure’s roof, floor, and general appearance from the outside. The Tent’s general circus-tent appearance must be preserved, particularly the color scheme of the structure.[14]

Additionally, the technology that was used to create the original roof is historically significant; the roof still has its original cables, which should be maintained. While the general roof structure is important to preserve, using the same material and mimicking the look of the original roof are not necessary.[15]In our interview with John Krawchuk we came to the conclusion that the historical significance is embodied more in the appearance rather than the material, and with advancements in technology an intervention could replicate the character and still take advantage of current and new innovation. We thus recommend restoring the original cables, referencing the original roof design, but replacing the roof with either a tensile fabric or space-frame system.

The floor of the Tent is also significant, as it contains the terrazzo map of New York State from 1964. However, the floor is in poor condition; there is currently gravel covering the terrazzo as a conservation technique, to ensure that weeds do not grow through the panels and roots do not break it apart.[16] Preservation techniques have not yet been successful; fourteen panels that were removed for conservation were placed back into the floor this year and the conservation techniques did not hold up.

A tile from the Pavilion’s floor

The floor is an important piece of art, however, a preservation technique that works has not yet been identified.[17]

In recognition of both the importance of the floor and the challenges of leaving it in place, we propose two options. The first is to place a secondary glass floor overtop of the existing terrazzo. This would allow the original floor to remain in place, but not suffer wear and tear from new use. This option presents an opportunity to add another layer to the existing map, as a current map of the state could be placed on the glass floor for visitors to compare with the map from the 1960s. The challenges inherent in this strategy are protecting the terrazzo from the elements, as the structure would be impossible to completely enclose, and there is a possibility that adding a floor may change the look and feel of the space, also ensuring that the new floor is strong enough to support activities in the structure – for example, light vehicles driving for event set-up. A second option is to remove the terrazzo map from the floor of the Tent and place it on display somewhere else. Although this would alter an important feature of the structure, it would allow for easier preservation, as the panels would not need to be exposed to the elements.

In considering new uses for this site, there were specific challenges and context to be considered. Many cultural events currently take place close by, and while the Tent of Tomorrow should not compete with existing facilities in the park, there is an opportunity to complement those sites, particularly for events that draw 100,000 or more attendees.[18] A major challenge to hosting events is noise; because of the site’s proximity to LaGuardia airport, every time a plane flies over any sound being produced in the park is drowned out. While the structure could potentially be enclosed to address this challenge, it would be difficult to enclose it in a way to keep noise out, and that would likely have a negative impact on its historic character.[19]This is more of a concern for events such as concerts than for festivals or similar activities.

Taking all of these factors into consideration, we propose a flexible space that caters to different audiences over different seasons. During the park’s high season of April to October, the Tent of Tomorrow would function as an event space, available to the surrounding communities, corporate users, and general event users. This space would be available to the community, free of charge, for theatre, art, cultural, or other events; it would be available to rent for corporate users for their events, and to the broader public for events such as weddings. The space would also be available as a complementary space for the cultural events that already take place close by in the park. In the winter, the space could be converted into a sheltered outdoor ice rink. This use is dependent on how the terrazzo floor is addressed, however if pursued it would provide a draw into the park during a time when there are far fewer people using the park’s outdoor facilities.

Pathways

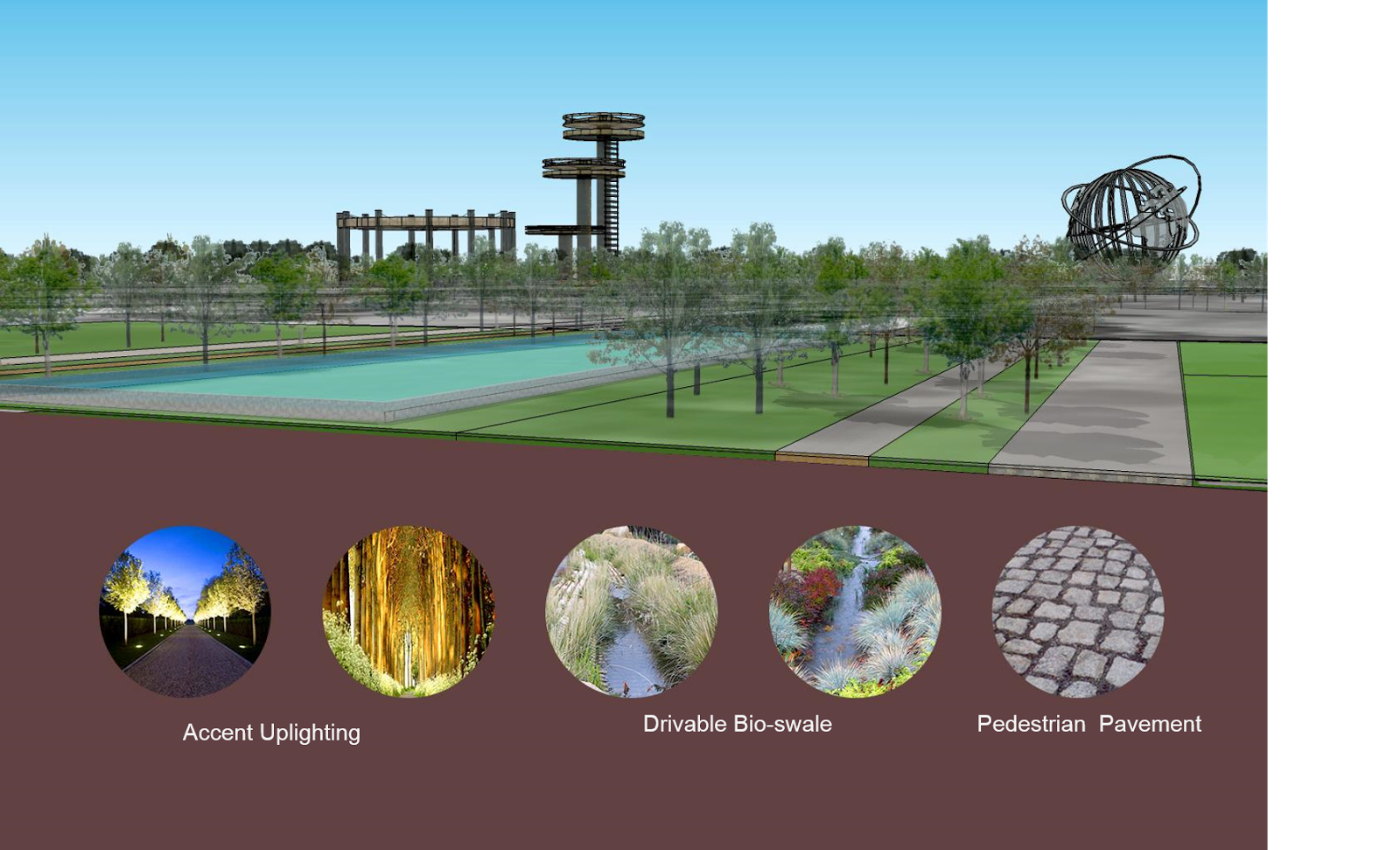

Gilmore Clarke designed the pathway system for the 1939 World’s Fair; the plan for 1964 was based on that same design. Designed in the Beaux-Arts style, the paths are a historic and defining feature of the park. However, because they were designed with vehicles in mind, the current system can feel overwhelming for its pedestrian users.

In considering changes to the pathway system, a number of factors must be kept in mind. A major concerned outlined by John Krawchuk is how to maintain the authenticity for Gilmore Clarke’s plan without making the park feel like an empty space.[20] The park’s development is largely tied to vehicles in the park; now that the area is more pedestrian-centered; there is a feeling of pedestrians imposing on vehicular space. When transforming the park to be more pedestrian friendly, it is important that pedestrian areas – such as the path system – feel that they are intended for those users.

From a preservation perspective, it is important to preserve the pathway system that is left today. Some of the paths have been lost over time as the park was developed. For example, the development of the USTA Tennis Center and some of the soccer fields resulted in paths being eliminated.

Given the purposeful symmetry of the design, it is critical to understand the elements that remain and ensure that no other paths are removed. Additionally, the trees alongside the paths were part of the and thus must be considered part and parcel with the pathways themselves.[21]

Current park needs are also an important consideration. While mainly used for pedestrians, the pathways in the historic core are also used for parks vehicles, and must be a minimum of 8 feet wide. These pathways are also used for vehicles during major events such as the US Open, and must be able to continue serving this function.[22]

In recognizing the historical significance of the pathway system, while acknowledging that there is flexibility in certain system characteristics, we propose the following adaptations:

Pavement: Change the pathway material from asphalt to a material that is more permeable and clearly pedestrian-oriented. This serves two purposes – it serves as green infrastructure to reduce stormwater runoff, and better defines these spaces as pedestrian. The new material would require the strength to handle vehicular traffic, ensuring that the park does not lose functionality; however, a more visually pedestrian environment would make it so that drivers feel that they are imposing on pedestrian space, as opposed to the current feeling that pedestrians are walking down auto-oriented road.

Curbs: Similar to the pavement change, removal of concrete curbs along pathways and replacement with a planted, vegetative barrier is recommended. The curbs delineate the edge of the path, in addition to helping drainage and preventing erosion;therefore, the replacement must have the same functionality. This could be a drivable bioswale, which would help with stormwater runoff, or a more simple planted edge.

Lighting & Definition: In recognition of the contribution of the trees to the pathway system and the importance of the Beaux Arts design, lighting should be added along the historic pathways to add definition to the area and its axes. Accent uplighting for the trees that frame the paths would create a visual axis after dark, and help focus attention on the historic core from both within and outside of the park.

Restore Symmetry: Through the addition of recreational facilities, some of the symmetry of the historic path system has been lost. This symmetry should be restored where possible. This need not be paths of the same width or material; any type of pathway, whether woodchip, gravel, or another material, that reflects the plan of the original path system would work to create a visual trail, restoring the lost historic footprints. This strategy allows the park to celebrate its history without impeding function.

Because we’re working within a changed environment we don’t have access to the same space.

Sustainability

Sustainability was a major focus of our planning and design efforts, however, Flushing Meadows does not have a park-specific sustainability plan. Recognizing the sustainability potential of this site, the Strategic Framework plan outlined measures for the park to be a “vanguard of sustainability.”[23] Building on this concept, we present additional sustainability considerations that should be integrated into future park plans. These considerations fall into the three pillars of sustainability discussed previously: environmental, economic, and social.

Environmental considerations relate to on-site water runoff and flood resiliency. There is currently a surplus of hardscape surfaces on the site; strategies such as bioswales and decreasing impervious surfaces can increase the land absorption rate of stormwater. Flood resiliency is also important, as the park was flooded during Super Storm Sandy and will also be affected by the soon-to-be-updated FEMA flood zones.[24] The site is somewhat uniquely affected by storm flooding, as the floodwater comes mainly from tidal surges and not rainfall. This means that brackish water is flooding the park, which can lead to a loss of trees, among other effects.[25]

Economically, the biggest challenge facing the park is financial uncertainty. All revenue generated in the park goes to the City’s General Fund; while the City supports the park, it does not have the ability to generate its own revenue.[26] The park thus relies on a number of different funding sources, particularly for capital projects, meaning that there are likely to be financial barriers to pursuing new projects. The park is already addressing some of these issues through the creation of a park conservancy; other parks with these organizations are able to keep much of their revenue, and the hope is that Flushing Meadows will benefit in the same way. While the City is likely to resist giving up much of its current income, there may be negotiation potential for revenue from new events.[27] We believe that the creation of this park conservancy is a major step towards economic sustainability for the park. Additionally some of our proposed uses have revenue-generating potential; as new uses, the park is more likely to be able to keep some of this revenue.

Socially, our main sustainability focus is to keep the park open and accessible to its surrounding communities. There are many communities surrounding the park, and diverse groups of people use the site for recreation and leisure. It is important to emphasize the park’s historical significance while continuing to enhance connection to communities in the area. In recognition of this, our designs emphasize the historical character of the site while also emphasizing access and activity. We also propose a community access strategy similar to the existing structure of the Queens Museum, providing for free or reduced rate access for individuals and organizations from the surrounding communities.

Next Steps / Recommendations

The design concept developed in this research begins the process of sustainable adaptation of this site, however, there is more that can be done – and more groups that are doing this work. In coming up with our proposals, we were careful to consider what other organizations are currently focusing on to ensure that we are complementing their work. These include People for the Pavilion (working on community perceptions and reuse options for the New York State Pavilion), the Design Trust for Public Space (working on a park-wide way finding and signage study), and the Flushing Meadows-Corona Park Conservancy (working on various funding and other park projects).

Wayfinding and the path system were both priorities raised at the beginning of this project, however we recognized that a comprehensive, park-wide wayfinding study is currently being conducted by the Design Trust for Public Space and the Queens Museum. As such, we focused our efforts on sustainability and user experience in the historic core, and have not included recommendations for these broader topics in this report.

While we recommend a number of actions, this need not— and likely cannot—be undertaken all at once. As such, we recommend a phasing of these strategies, based on funding and other project capacities. Some of the smaller-scale interventions, such as the public art space and tower lighting, can be pursued relatively soon with funds that have already been secured for work on the fountains and the Pavilion. The larger scale projects, such as the Fountain of the Planets and the reuse of the Pavilion, will require a longer timescale to account for planning and funding.

Conclusion

Despite the unique stories, visions, and evolution behind each of these sites, the commonalities underlying the problems they share have fueled a range of similar approaches to problems of sustainability. Each site, across time, has served as a venue for experimentation in approaches to sustainability, adaptability, and historic preservation. As these former fair locales attempt to meet public needs, celebrate modernist history, and adapt to changing priorities and circumstances, managers and planners can look to sister sites for inspiration and guidance. The four North American sites have, each in their own way, found methods to attempt to confront future challenges while maintaining harmony between social, environmental, and economic qualities and honoring the historic heritage that exists in these locations.

Looking into the future, though each of the sites faces serious challenges in the form of shifting financial support landscapes, access barriers, tensions between different uses, and friction between historic character and contemporary preferences, development pressures and insufficient funding to meet all needs, the innovative range of solutions developed to address these issues at different locations around the country is a sign of hope. Through examining multiple sites in detail and considering the lessons they can offer when considered as a whole, it is possible to develop a sense of which themes, design interventions, and policy solutions are most important to support. Lessons also abound for the design and planning of contemporary sites with large physical footprints.

Footnotes

[1] John Krawchuk, phone interview by authors, November 14, 2014.

[2] Ibid.

[3] Ibid.

[5] Krawchuk, John, phone interview by authors, November 14, 2014.

[6] Ibid.

[7] Jelte Rozema & Timothy Flowers, “Crops for A Salinized World,” Science Magazine, December 5, 2008, http://www.environmentportal.in/files/Crops%20for%20a%20salinized%20world.pdf, p. 1479

[8] ”

[9] “National Register of Historic Places,” http://www.nps.gov/nr/listings/20100625.htm

[10] Khan, Salmann, phone interview by authors, November 18, 2014.

[11] Quennell Rothschild & Partners, LLP & Smith-Miller + Hawkinson Architects, “Flushing Meadows Corona Park Strategic Framework Plan,” New York City Department of Parks and Recreation, 2005.

[12] Janice Melnick, tour of Flushing Meadows Corona Park, September 12, 2014.

[13] John Krawchuk, tour of Flushing Meadows Corona Park, September 12, 2014.

[14] Krawchuk, John, phone interview by authors, November 14, 2014.

[15] Ibid.

[16] John Krawchuk, tour of Flushing Meadows Corona Park, September 12, 2014.

[17] John Krawchuk, phone interview by authors, November 14, 2014.

[18] John Krawchuk, tour of Flushing Meadows Corona Park, September 12, 2014.

[19] John Krawchuk, tour of Flushing Meadows Corona Park, September 12, 2014.

[20] Ibid.

[21] Krawchuk, John, phone interview by authors, November 14, 2014.

[22] Melnick, Janice, email message to authors, November 17, 2014.

[23] Quennell Rothschild & Partners, LLP & Smith-Miller + Hawkinson Architects, “Flushing Meadows Corona Park Strategic Framework Plan,” New York City Department of Parks and Recreation, 2005, p. 43.

[24] Melnick, Janice, phone interview by authors, October 31, 2014.

[25] Ibid.

[26] Janice Melnick, tour of Flushing Meadows Corona Park, September 12, 2014.

[27] Ibid.