Southeast Asian Languages at Cornell An interview with Professor John Wolff

John Wolff, professor emeritus of linguistics and Asian studies, was active at Cornell from 1963 until 2002. Lauren Kelly and Lucia Pannunzio interviewed Professor Wolff in fall 2021. The interview was part of a class project conducted by Lauren Kelly, Bridgit Haggerty, Lamia Simrin, and Lucia Pannunzio for Dr. Yarden Kedar’s Early Multiculturalism and Multilingualism class.

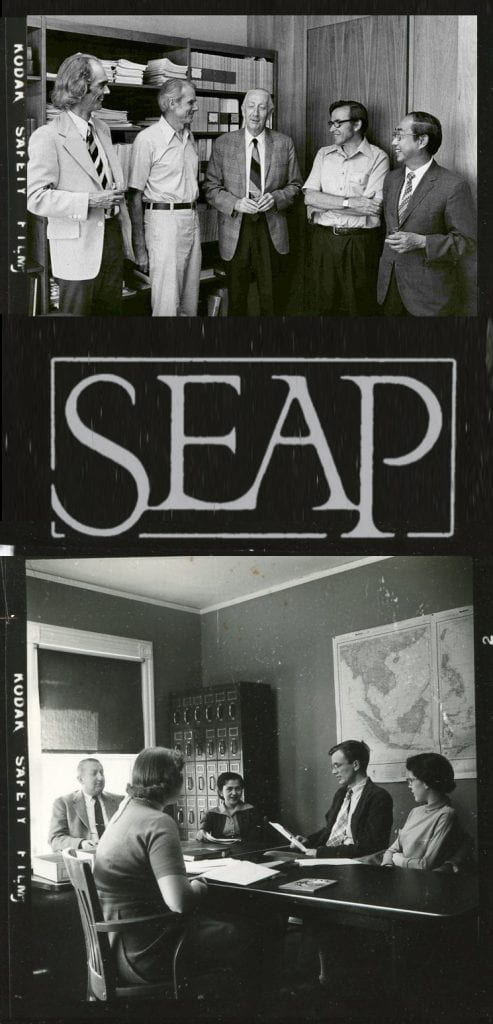

Professor Wolff’s long tenure provided him with a unique perspective on the development of Asian studies and language teaching at Cornell. Although his primary appointment was in the department of Linguistics, he also served as the director of the Southeast Asia Program (SEAP). As a language instructor, he primarily taught Indonesian, but he also taught Tagalog, Javanese, and Cebuano.

I can’t remember now, but there were just one or two in East Asian literatures that were in Asian studies and no other department. That has changed.

John Wolff

Credit: Courtesy of John Wolff and Southeast Asia Program

Development of Asian studies and the Southeast Asia Program

When I first came, the department of Asian studies was a conglomeration of people, except for maybe four professors in the department. Almost all of the other people were joint-appointees. I was in the departments of linguistics and Asian studies, but I considered my primary department in linguistics. That was the case of almost everyone in the department, except for, I think there was a professor of Chinese literature and a professor of… I can’t remember now, but there were just one or two in East Asian literatures that were in Asian studies and no other department. That has changed. Now the department is full of people that are just in, or primarily in, the Asian studies department. The Asian studies department is their locus. Also the languages, all the Asian languages were not in Asian studies, but they were in the department of linguistics. They were hired and maintained by the department of linguistics, and that changed just about at the time that I retired. The language programs were taken out of the department of linguistics and put into the different departments… and the Asian studies language department now has all lecturers that are in Asian studies… So the complexion of the department has changed

…and the thing about the SEAP, the programs in this university do not have the right to hire and fire, as far as I know, certainly the SEAP did not. The hiring and firing was in the department, and so we depended on the department to hire someone in the Southeast Asian field if we had a retirement, so if a professor of anthropology who was teaching in the Southeast Asian field was in the SEAP, but then that person retired, they hired another person, but there was no guarantee that they would hire someone in Southeast Asian field. They might hire someone in Latin America or someplace else. So that was one of the big problems that I faced. And here we imploded, we had more than half of our faculty retiring, and we had to persuade the departments to confine their search to Southeast Asia persons.

Now people at the level of lecturer attend meetings and have a vote. . . It’s absolutely a good thing.

Changes in the role of lecturers in the Southeast Asia Program

University, is that the lecturers are given much more of a role in running the department and making decisions than they were previously. When I came, and for most of the time of my career, the lecturers were excluded from all decisions and actually excluded from meetings. Now people at the level of lecturer attend meetings and have a vote. I think it’s a general thing that’s been happening throughout society in this country, that there has been a democratization where people at a lower level are given more rights and more privileges and more responsibilities than they used to be, in industry as well as in academia. It’s not just Cornell, I think you find this everywhere. And do I think it’s a good thing? Absolutely. I mean, one of the pressures, there was a great deal of dissatisfaction among the lecturers in our department… They expressed deep dissatisfaction and there was lots of rumbling and lots of problems which gave everyone a headache. And one reason that they gave us these problems was because they were excluded and they were pressured to let their voices be heard. So it’s a good thing. It’s absolutely a good thing. I’m not a great believer in hierarchy.

right: 2018 Southeast Asian Languages Celebration. Credit: The Cornell Daily Sun

Because of Professor Wolff’s long tenure at Cornell, he has a deep knowledge and perspective on the various methods that have been employed in language teaching at Cornell.

It was an expensive proposition, cost the university a lot of money to have a course just for one or two people. They’d have to pay somebody a lot of money for very few students, but they did it, and that was good.

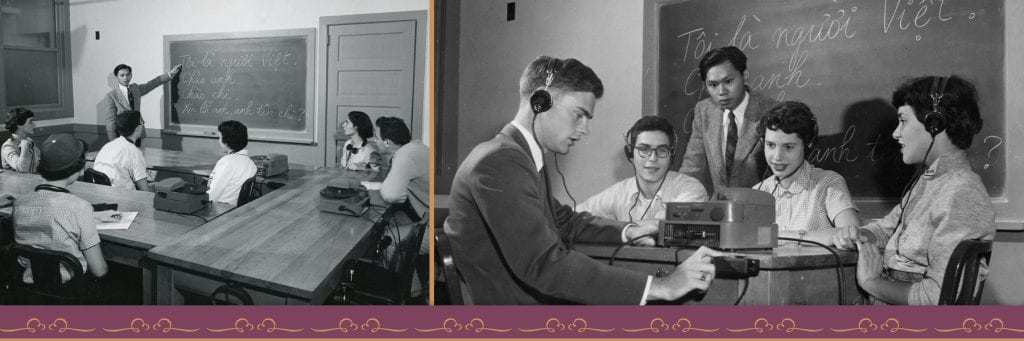

Teaching

There was a great problem because there were some of these languages that were very rarely taught, like Burmese let’s say, or Cambodian at the time. There were only one or two people that would want to take it every year, but they offered it, because the people that wanted to take it had a reason to take it, and we should have been offering it. That was one of the big problems that we had in language teaching, and Cornell did a good job. It was an expensive proposition, cost the university a lot of money to have a course just for one or two people. They’d have to pay somebody a lot of money for very few students, but they did it, and that was good.

I taught my courses in Indonesian, Javanese, Tagalog, and Cebuano. Four languages, and I had to make materials for every single one of them at all levels

Team-teaching model

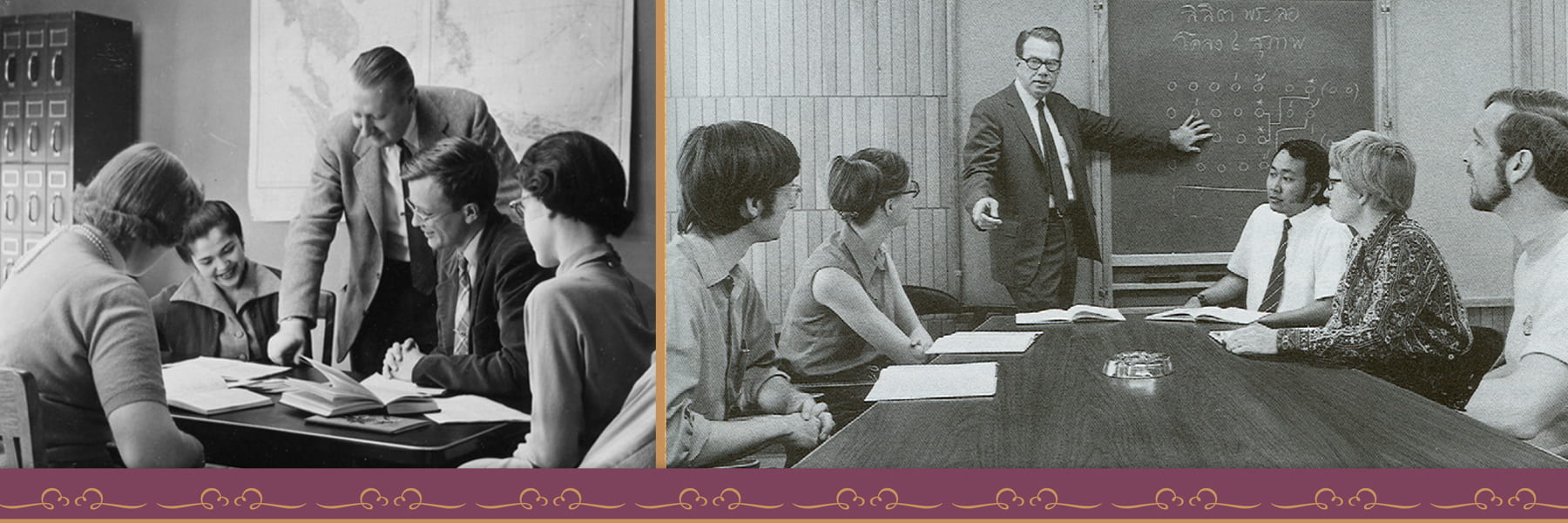

For many years Cornell’s language program had a unique teaching model in that most language courses were team taught by both a native speaker and a linguist.

There’s one thing about language learning and language teaching, you don’t do it if you’re speaking English. You can’t make a person learn how to speak Japanese by speaking English. You gotta speak Japanese. The person who is learning Japanese learns Japanese by hearing it and using it, and nothing else really works. Nothing else really makes them learn the language. It’s like playing the piano. You learn how to play by playing. You can learn about the theory, however, people do need to know about the theory. They need to be able to ask questions. People always ask questions, how does this work, how does that work? They need to do it. The team-teaching method gives them the opportunity of doing that without interrupting the class. In other words, the rule was always in the Indonesian class, in my classes, and in the Japanese class, nothing but the target language was used. You stick to the lesson, you did speaking and you did hearing, and you did whatever you did to increase the active participation of the students. But the students have questions, they are told, “You can ask your questions. Write it down, and you can ask it during the time you are in the lectures which do not take as much time.” Lectures take maybe 20% of the class time, the rest is speaking and hearing. And that’s effective. I had monolingual teachers, mostly monolingual teachers for Indonesian, and it was great, because the students had no way of talking English to those teachers, and it kept the class in Indonesian. They had a question, they asked me.

Right: Circa 1970, R. B. Jones, standing, leads a discussion with students, left to right, Craig Reynolds, Lorraine Gesick, Thak Chaloemtiarana, Dolina Millar, and others. Sources: SEAP Bulletin Spring 2022

I think the basic idea in my teaching was to make the students speak and make them correct themselves, make them be able to hear what they were doing and make them able to feel themselves, if they were pronouncing it right or not, or if they were sort of going along with the way native speakers speak, or if their grammar was correct and they were using the language well. And, the basic idea of my teaching was always, “Keep the students speaking, keep them speaking.” The teacher does nothing but speak a little bit, give them the model, just something, so they have something in their brains so they know what they should be able to get, but make them try to do it. That isn’t holding the whip above them and saying, “Hey you! Do this! Do this!” I make it sound terrible, but actually you make them want to do it. You show them a way to do it. You show them how they can do it.

Developing teaching materials

My first difficulty was that there were no pedagogical materials. I mean for Indonesian there were some around, but they were abysmally bad… So that was one of the problems, that these materials were just absolutely terrible. So one of my problems was just to make the materials. I taught my courses in Indonesian, Javanese, Tagalog, and Cebuano. Four languages, and I had to make materials for every single one of them at all levels.

Credit: Courtesy of John Wolff and Southeast Asia Program

The main one was Indonesian, that had always been taught at Cornell. Then the second language was Tagalog, which I introduced because it was the main language in the Philippines… and then I also taught Javanese, which is not the main language in Indonesia, but it’s a very widely-spoken language. And some people wanted to learn that, so I developed materials for a course in Javanese at Cornell, then Cebuano, because I happened to be interested in that language and it’s one of the local languages of the Philippines, spoken by a large number of people, so occasionally a student would want to learn it.

All my teaching was done in the era before computers were just coming into teaching, and computers were just coming into the pedagogical methods. And I must say that with computers, a lot of things can change.

Technology in language teaching

All my teaching was done in the era before computers were just coming into teaching, and computers were just coming into the pedagogical methods. And I must say that with computers, a lot of things can change. For example, in my last years I developed a method of teaching Indonesian where the grammar was so well explained in pictorial terms that the students really needed little by way of explanation. They could understand the rules of the grammar just by the various exercises that we could do on the computer with them. We could present the rules through some kind of game or through some kind of pictures, and they could learn the rules through those games. It makes a great difference to the way you would structure your instruction nowadays. Just the existence of computers and the kind of materials that can be developed…make for a very different kind of classroom activity.

Credit: Courtesy of John Wolff and Southeast Asia Program

Authors’ reflection