Kimi Gengo: Author, Advocate, Asian American

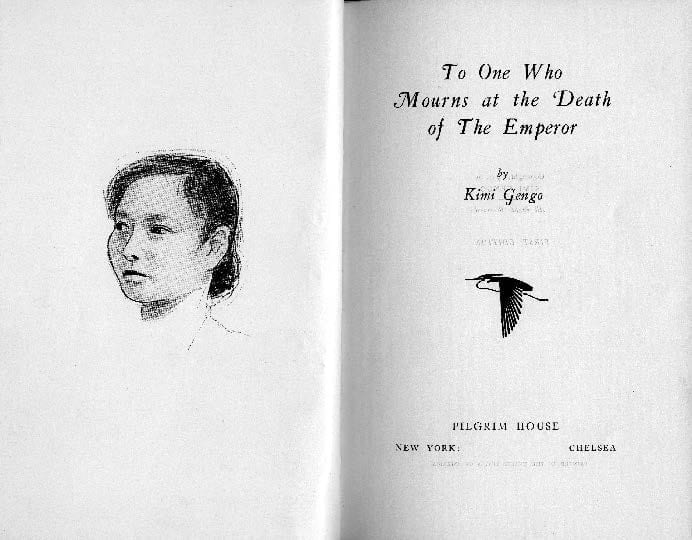

Frontispiece of Kimi Gengo’s book, To One Who Mourns at the Death of The Emperor (1933), featuring a drawing of her by her husband, Bunji Tagawa. http://www.discovernikkei.org/en/journal/2020/7/1/tagawa-1/.

RETICENCE

Be bold, my heart.

And tell your lover.

All thoughts are told, but this:

Eternal loneliness.

Kimi Gengo (1903–1987) was a literary pioneer and advocate for Japanese Americans. Born on April 4, 1903, in Holualoa, Hawaii, Gengo attended high school in Suisun City, California before her family moved to Ithaca, New York in the early 1920s.[1]

“Ithaca Girl Shares Morrison Poetry Prize at Cornell,”

The Ithaca Journal, March 28, 1929, https://ithacajournal.newspapers.com/image/254685703/.

Gengo attended Cornell from 1924-1925 and 1928-1930, becoming one of the university’s earliest female Nisei (second-generation Japanese immigrant) students. During her time at Cornell, Gengo published her first verses in The Columns, a Cornell literary magazine. The Ithaca Journal, on May 11, 1926, noted Gengo’s contribution to The Columns, if only to characterize it as an exotic fascination: “Gengo comes again with the Oriental flavor.”[2] Nevertheless, Gengo proved that her literary talent was much more than a “flavor,” winning the Morrison Poetry Prize at Cornell two years in a row and receiving an Honorable Mention for the Byner Prize from the nationally-renowned Poetry magazine in 1929.[3] At Cornell, she also met two people who would change her life: her future husband, artist Bunji Tagawa, and master’s student Philip Freund, who would later publish and write the introduction for her book and become a well-known author and theater historian in his own right. After graduating, Gengo worked briefly as a stenographer at the Farm Bureau in Ithaca before she and Tagawa married in 1932 and moved to Brooklyn, New York.[4]

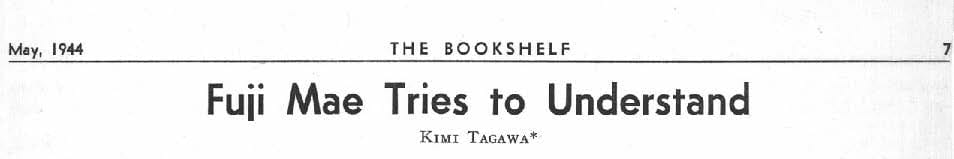

In 1933, Gengo published To One Who Mourns at the Death of the Emperor, a collection of poetry, verse, and translations, through Philip Freund’s newly-established publishing firm, Pilgrim House. It was the second book ever published by a Nisei woman in the United States (the first was Kathleen Tanagawa’s memoir Holy Prayers in a Horse’s Ear published one year earlier).[5] In the volume, Gengo’s poetry, which employed modernist techniques like free verse and impressionistic imagery, was divided between two sections, the first drawing directly on Japanese themes and scenes, and the second on more general subject matter. The third section comprised Gengo’s translations of Japanese poems, including some of her father’s haikus and tankas (31-syllable short poems).

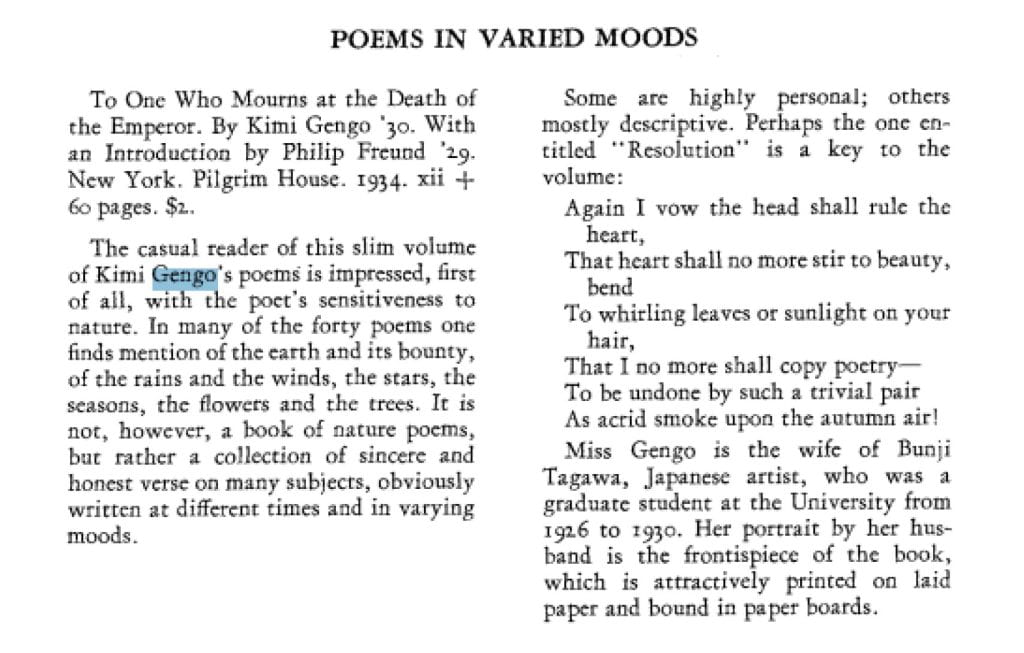

To One Who Mourns at the Death of the Emperor attracted national attention, drawing mostly favorable reviews, though both praise and criticism were usually couched in prejudice and stereotypes about Japanese people and culture, ranging from microaggressions to blatant racism. The New York Times Book Review, for one, in an article entitled “Six New Books of Verse by a Diversity of Poets,” reviewed To One Who Mourns at the Death of the Emperor, writing: “This little book with its dignified and unusual title is from the pen of a Japanese…There is no profusion here, for it is not in the way of Nippon’s art to be profuse.”[8] Critics tended to directly target Gengo for her racial background; The Saturday Review of Literature, for example, summarized her book as: “A Japanese woman writing in English. Not very memorable.”[9] The Cornell Alumni News also reviewed Gengo’s book in their December 13, 1934 issue, thankfully dispensing with the racialized language found in many other publications.[10]

The outbreak of World War II changed the lives of Gengo and her family dramatically. Tagawa, a Japanese citizen, was placed under house arrest, leaving Gengo, an American citizen, to run errands and take care of business for their family.[11] During this period, Gengo turned her focus to activism, becoming a member of the national board of the YWCA (Young Women’s Christian Association) in the early 1940s. She became involved in the YWCA’s Girl Reserves, a program established in 1918 to educate girls about wartime issues and encourage them to participate in the war effort. It was the first YWCA group dedicated specifically for teens and one of the first to welcome minorities, support minority-driven advocacy, and foreground conversations about race and diversity.[12] Gengo used her platform to promote racial tolerance and understanding of cultural differences, speaking at national Girl Reserves conferences about the YWCA’s work helping Japanese-American internees and African Americans.[13] She also drew on her own background to educate young people about Japanese-American experiences and perspectives, talking candidly about her feelings of otherness in both Japanese and American contexts.[14]

From 1943-1944, Gengo published a three-part series of stories in the YWCA’s magazine for the Girl Reserves, The Bookshelf, about a Japanese-American girl named Fuji Mae, educating readers through fictional conversations about differences between American and Japanese culture and the complexities of immigration and assimilation.[15]

Photo of National YWCA dignitaries at the Girl Reserve midwinter conference in 1943, including Gengo (front row, center).

“Phases of Post-War World Discussed,” The Hartford Courant, March 14, 1943,59,

Title of the third installment of the “Fuji Mae” series, “Fuji Mae Tries to Understand” in The Bookshelf 27, no. 9 (May 1944), 7-8,

https://compass-stage.fivecolleges.edu/object/smith:387228#page/1/mode/2up.

In the third installment, “Fuji Mae Tries to Understand” (1944), Gengo tackled anti-Japanese racism head on, addressing the injustice of internment camps and citing reports and scholarly articles to discredit the widely-held suspicion that Japanese civilians or Japanese Americans committed sabotage related to the attack on Pearl Harbor.[16] This story is a remarkable example of fiction written and published by a Japanese American about internment as it was occurring.

After the end of World War II, Gengo apparently did not continue writing in a public capacity, dedicating her energies to social work instead. She taught at the New York School of Social Work from 1950–1952,[17] and she worked as a Senior Social Worker on the New York State Workers’ Compensation Board in the 1950s and 1960s.[18] She lived a relatively quiet life in Brooklyn and passed away in 1987. She rarely discussed her past literary career or her work with the YWCA, even with close family members.

Whether she was writing poetry or speaking at conferences, Kimi Gengo increased awareness and representation of Japanese Americans on her own terms. She may never have gotten to appreciate the historical significance of her work, but it’s time that Cornell did.

Kimi Tagawa (far right) representing the New York State Workman’s Compensation Board at the Burke Foundation’s annual seminar on rehabilitation.

Staff photo by Ray Hoover, The Daily Item, March 14, 1962, 32,

Notes

[1] Greg Robinson, “A Union of Artists: Kimi Gengo and Bunji Tagawa – Part 1,” Discover Nikkei, July 1, 2020, http://www.discovernikkei.org/en/journal/2020/7/1/tagawa-1/.

[2] “‘The Columns’ Lives Up to Standards In Second Issue,” The Ithaca Journal, May 11, 1926, https://ithacajournal.newspapers.com/image/254386691/.

[3] M. G. B., “The Week on the Campus,” Cornell Alumni News 32, no. 12 (December 1929): 167, https://ecommons.cornell.edu/bitstream/handle/1813/26944/032_12.pdf?sequence=1&isAllowed=y.

[4] Robinson, “A Union of Artists.”

[5] Robinson, “A Union of Artists.”

[6] Kimi Gengo, “This Thing, My Soul,” To One Who Mourns at the Death of the Emperor (New York: Pilgrim House, 1934).

[7] Tessin Gengo, “Tankas (II),” To One Who Mourns at the Death of the Emperor (New York: Pilgrim House, 1934).

[8] Percy Hutchinson, “Six New Books of Verse by a Diversity of Poets,” The New York Times Book Review, January 14, 1934, https://timesmachine.nytimes.com/timesmachine/1934/01/14/issue.html.

[9] Robinson, “A Union of Artists.”

[10] “Poems in Varied Moods,” Cornell Alumni News 37, no. 12 (December 1934), 3.

[11] Robinson, “A Union of Artists.”

[12] “A Moment in Our History: Touching the Lives of Future Generations: From Girl Reserves and Y-Teens to Girls’ Summit,” YWCA O’ahu, April 28, 2020, https://www.ywcaoahu.org/ywca-oahu-120/2020/4/28/a-moment-in-our-history-touching-the-lives-of-future-generations-from-girl-reserves-and-y-teens-to-girls-summit#:~:text=The%20Girl%20Reserves%20Program%20started,first%20program%20specifically%20designed%20for.

[13] “Phases of Post-War World Discussed,” The Hartford Courant, March 14, 1943, 59, https://www.newspapers.com/image/369905949/.

[14] “Only Jap Faces Tell Those Born Here They’re Different,” The Record, December 10, 1942, 11, https://www.newspapers.com/image/489763005.

[15] Robinson, “A Union of Artists.”

[16] Kimi Tagawa, “Fuji Mae Tries to Understand,” The Bookshelf 27, no. 9 (May 1944), 7-8, https://compass-stage.fivecolleges.edu/object/smith:387228#page/1/mode/2up.

[17] Robinson, “A Union of Artists.”

[18] The Daily Item, March 14, 1962, 32, https://www.newspapers.com/image/714982287/.