Bringing Back Quechua

There were no faculty at the university who spoke or would be able to teach Quechua until Soledad Chango, a graduate student and native Kichwa speaker (a branch of Quechua), from Ecuador, joined the language faculty in August of 2021.

Soledad Chango shares her experience as an instructor teaching Quechua, which was brought back to Cornell as a language course after a 15-year hiatus. Quechua was initially offered from the 1950s to 2006. There were no faculty at the university who spoke or would be able to teach Quechua until Soledad Chango, a graduate student and native Kichwa speaker (a branch of Quechua), from Ecuador, joined the language faculty in August of 2021[1]. In the 2021-2022 academic year, one section of Elementary Quechua I and one section of Elementary Quechua II were offered in the fall and spring, consecutively[2][3]. It is interesting to note that American Sign Language, the Cayuga (Gayogo̱hó꞉nǫ’) language, and Quechua began to be offered because of students expressing their cultural and inclusivity-related needs for them.

This interview was conducted as part of an assignment for Yarden Kedar’s course, HD2350: Multilingualism and Multiculturalism in Early Childhood, in fall 2021. Soledad Chango has since graduated from Cornell and is now an English professor at the Pontífica Universidad Católica del Ecuador (PUCE).

Interview Excerpts

Question 1: Can you briefly talk about your background with Quechua?

The course I am teaching is called Quechua, but the variety that I speak is called Kichwa. My native language I learned it since I was born, so in my community, called Salasaca, most of us grew up learning our native language. This is my mother tongue, that’s why I speak Kichwa.

Question 2: What motivated you to teach Quechua at Cornell?

Teaching in general is something that I think is part of my personality. I always liked to share things, and I think since the beginning of my academic studies I always shared things to my friends. I have always been working on that society, just sharing content in general, so I really like that thing. And when it comes to teaching in a professional life, in general, I think I wanted to become a teacher because I had a very good English teacher in my elementary school. So, the first time I got my English class, I was ten years old, so I really liked that class and liked English itself. I was like, “Oh this is so nice,” and I love how the professor speaks, and the way he was teaching me was very cool, so this was the first option for my professional life. And then when I graduated from high school, I knew that something I really liked was teaching, and it kept being English at the first time. I studied languages in the university, and I became a teacher in my career at some point. I’ve been teaching traditional dancing, to embroider, to play the violin, so I have different sites of teaching, but here at Cornell is the first time teaching my native language. So, it’s been challenging but it’s been really cool.

Question 3: What is the class composition for your Quechua class like—are there many international students or do most students share similar backgrounds?

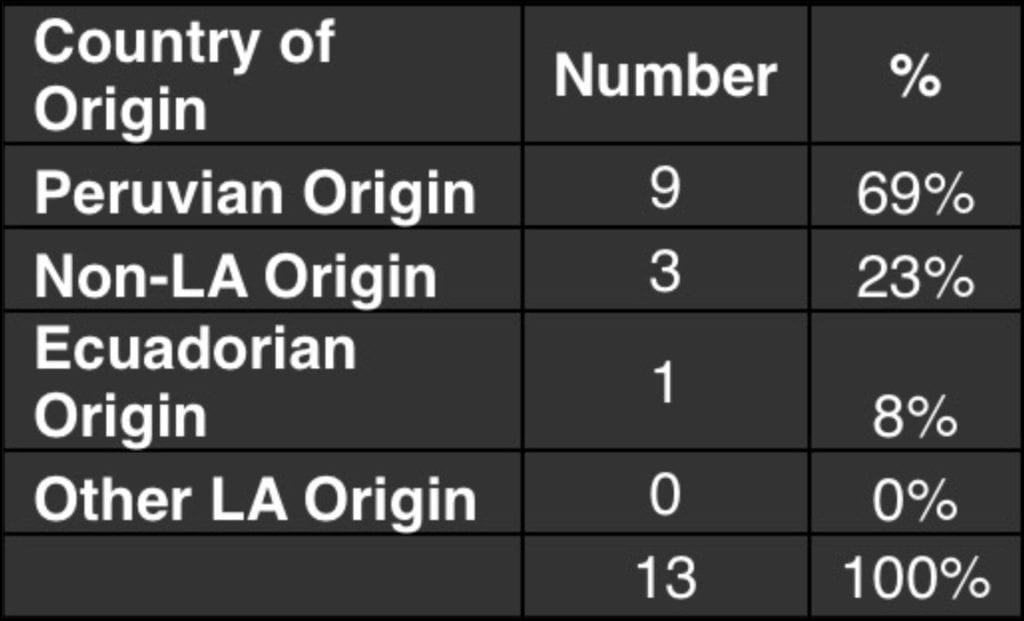

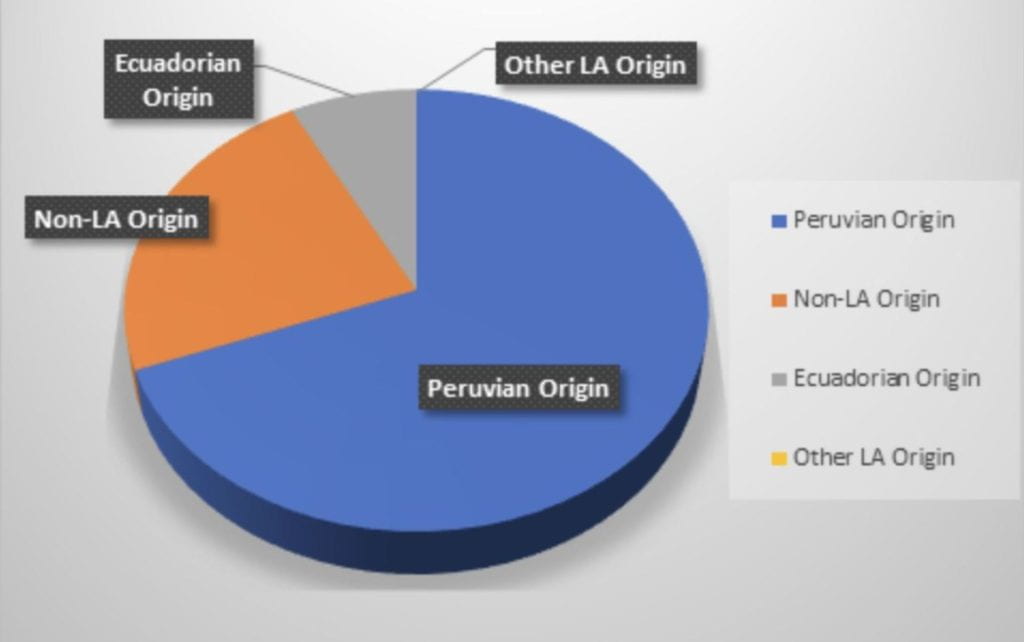

In general terms, most of them are Peruvians. I have 13 students. Eight of them are Peruvians, but not, I mean, most of them were born here and they are heritage students. So, their grandparents spoke Quechua, the main language, the main variety of the linguistic thing, one has Asian roots, and one has American roots that has nothing to do with heritage students, but they are conscious about what they are learning and conscious about the genocide that there have been some years ago with our language, and they are conscious about what they are going to do in the future with the language.

I always tell my family and friends that people here are proud of learning my native language, and we are not teaching our native language in our home country. And that’s something we must be proud about as native speakers, like the direct resource to keep our language strong.

I would like to mention the future, the reasons why my students have taken this language. I will mention one student who is learning chemical engineering, and she plans to become a teacher in the future. And what she wants to do is really impressive. You know that my native language, as it’s a language of minority, is a daily use language, so you can’t speak about science in Quechua, you can’t speak about medicine in Quechua; just those terms that are educational, that are out of daily life. So, she wants to finish undergrad and become a teacher and then teach science in Quechua. She is involved in a project: Quechua in Science, Humanities, and Technology. What they do is translate different chemical elements into Quechua. And she’s going to be a part of it, so she’s learning material that is going to be part of her future professional life. Another student is a PhD student learning anthropology. She is planning to go to Peru and study anthropology in a real life, in real practice with Quechua native speakers, so she’ll have direct communication with them. Another student is upset because he wasn’t taught Quechua by his grandmother, because they just were ashamed of teaching him Quechua because there was a killing scenario in the 1980s in Peru. So, every single person who had aspects of Quechua or of being indigenous or indigenous heritage were being killed, so their parents and grandparents wanted to protect him. He wants to continue speaking this language because this represents his cultural heritage. These are very strong reasons they are learning the language, and I really admire them because of that. Also, because in our native community, we are not teaching our children to learn our native language, it is very, very sad. Having people here far away learning our native language is very surprising. It’s something I always tell my family and friends that people here are proud of learning my native language, and we are not teaching our native language in our home country. And that’s something we must be proud about as native speakers, like the direct resource to keep our language strong. This is something amazing and I admire my students and if they see or hear this somewhere, let them know, please.

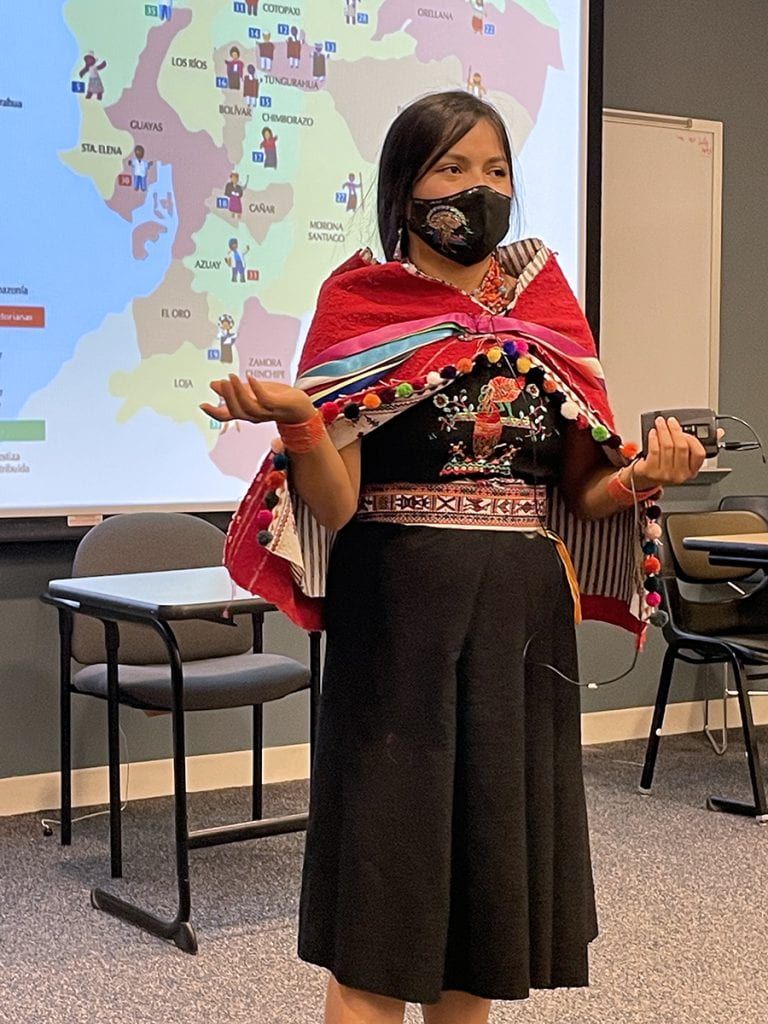

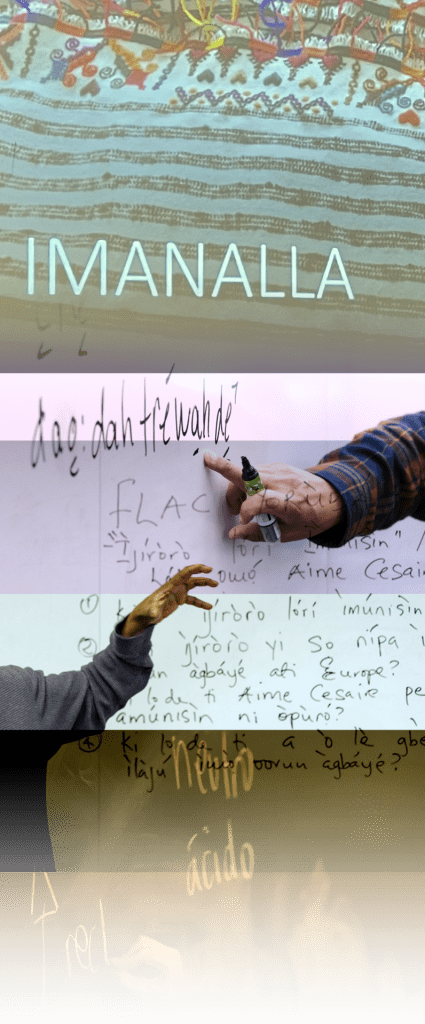

Soledad Chango presents at Onondaga Community College

Credit: Kathi Coleen Peck

Question 4: What are some of the challenges about teaching Quechua?

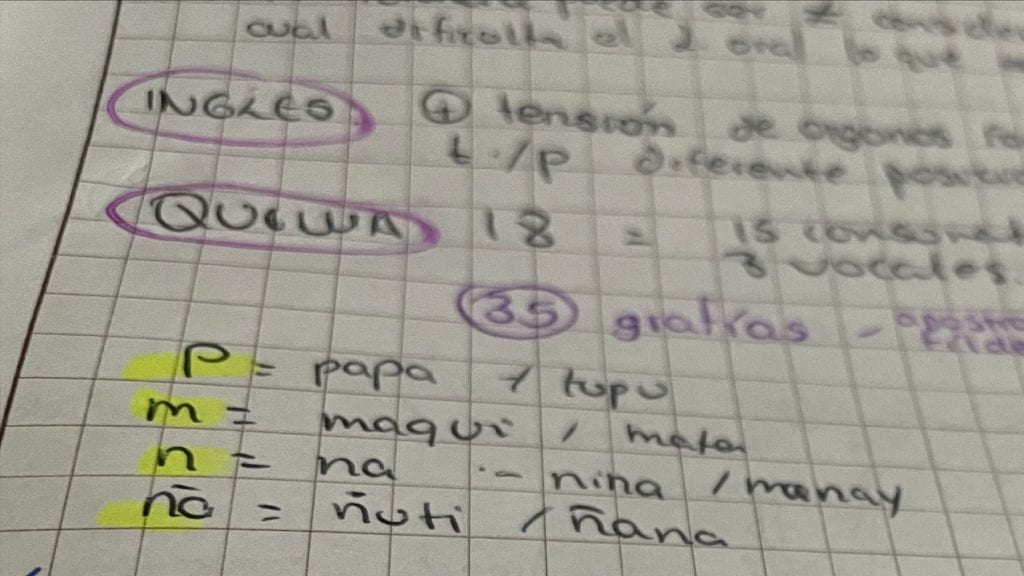

Actually, Quechua, and the varieties of Quechua, has been considered an endangered language. This is a language of minority in which it is hard to find resources on the internet, physical materials or easy access to where you can study it. A huge challenge that was very hard for me to work on was materials that I can provide to my students in the class. You can’t find a song that is in basic Quechua that is in 100% of Quechua words, you cannot find textbook in which you are going to find very good work for English native speakers. So, I had to work on that very hard, and as you know it’s just me here teaching my native language. I don’t have another Quechua native speaker who can help me with that. That sense of creating the material for my students was very challenging. What I did to solve that issue was make my family help me with conversations. I wrote about my mom, my sister, my brother, and I brought some tools, like native traditional clothing and ornaments we have so we can make class more authentic for students to understand. I try to be authentic and create my materials at the speed my students were getting the language itself.

Question 5: What do you think about Cornell’s initiatives to advertise and promote Quechua as a language option?

I think at the very beginning there was more than I expected, because we got 25 students enrolled in my course. So, it was hard for us to work with that number, and I asked the faculty to split this course into two different courses, but they didn’t give me that option because they knew that I am also taking some courses so it’s going to be a little bit hard for me. I’m glad they didn’t because they know what they were doing, but in that sense, I know that by the advertisement they did was really good. A lot of people have written to my email saying thank you so much for being here, and in that sense, I don’t think I would change anything. They did a good job.

Question 6: How do you foresee the future of Quechua instruction at Cornell and other educational institutions? What steps could be taken to promote foreign language education in general?

I consider that Quechua class has to be permanent for Cornell because Cornell has a lot of Hispanic students. As I said in the very beginning, my students are not just heritage students. There are also students who care about the language, not just because of their heritage, but in the sense of being inclusive and covering the diversity that Cornell has, I think this course must be permanent. It’s not just the sense of being permanent as a course, but making the language survive because this language is an endangered language. This is support for the language, for the people, for the culture, and you know that the language is not just isolated, it contains a lot of tools outside of it. So, this is just saving the interest of an entire culture and entire identity itself, so I really encourage Cornell to make this course permanent.

I’m really sad to say this but the future of my native language is dark in the sense of even UNESCO has considered it an endangered language. I have recently been looking at the numbers of speakers of the linguistic branch of the different varieties of Quechua, so just two languages—Quechua from Bolivia and Cuzco, Peru—have one million speakers. The other varieties, including my own Kichwa variety, has just 8000 speakers and the number goes down. So, it’s really hard to say that a lot of varieties of Quechua are going to die in close future. But I know that it’s just a matter of being conscious of who you are and where you come from. We have been working on that in my culture, too, to say our language represents us, our roots, our cultural identity, and who you are as a person itself. It’s something that I know a lot of people in my country are working on it, too. So even though the future seems to be kind of dark for this language, I know people are trying to make this strong.

What Cornell is doing right now with language is something I have to give big applauses. It’s been 15 years of absence of this language and fortunately a student asked to bring Quechua back. It’s not just the institution, but also the students, because in this case it was students who brought it. And fortunately Cornell supported them, and it must be done. It’s hard to say they must do it, but they at least have to try. If they have a lot of students enrolled in this course, they have to support them, to have a lot of students, advertise them, and have a big community in each university, and we can work on different materials as professors for students so we can have a lot of resources, and with resources motivate our students to keep on learning the language. This can be a chain for all the universities and professors, and just making a big community for Quechua being taught in a foreign space.

Ideas for the Future

Especially for endangered languages, Cornell should work on creating a database that contains enough resources to preserve the language and culture, and it should be sufficient enough for someone to use to learn the language without an instructor. One way this can be done is to recruit a team of students, professors, and native speakers from around the world to contribute to the database and perform outreach internationally to collect documentation. Documents can include a dictionary that is created by native speakers, cultural artifacts, writing/poems/songs, and more. These documents should be preserved in both a physical and digital format so it can be accessible across the world.

Just like Professor Chango was invited to Cornell to teach Quechua, Cornell can invite native speakers of other languages to teach students and practice their own English. This can mimic a dual immersion program, where students and teachers will be both learning and practicing each other’s languages. This can also help international students or students who are not as proficient in English to master two languages at once.

Since social media is so prominent in today’s time, it can also be used to teach and promote foreign languages. Students and professors from the language department can pair up with those from other disciplines such as computer science, business, marketing, and others to create websites and apps to promote foreign language instruction and distribute resources for people to learn a new language altogether. Cornell has the advantage of being a large, reputed university with many resources at its disposal to effectively promote this cause on both a national and global scale.

Credit: Julien Sobel

Author’s reflection by Pridha Kumar

Throughout my years here at Cornell, I (Pridha) have become acquainted with a diverse group of people in terms of major, culture, religion, and personality—an opportunity I perhaps wouldn’t have elsewhere. I think it’s really important to not only understand and respect the differences that exist among us, but also to appreciate the beauty behind them and how they make us unique. Prior to coming to Cornell, I wasn’t connected with my South Asian background and roots, however, after finding a group of students from South Asia, I fell in love with my culture and roots and actively find ways to connect with it by watching Indian movies, listening to Indian music, and asking my parents for their childhood memories. I proudly share these experiences with my friends, regardless of whether they are South Asian or not, and find that everyone has been appreciative and receptive of the stories I have to share. By being immersed in an environment that promotes diversity, I have also reconfirmed my love and passion for my roots and aim to incorporate it more into my everyday life, and carry traditions, language, and culture with me into the future and across generations. It is for moments like these that I appreciate the diverse environment Cornell has created, and I hope that we all take this diversity and inclusivity with us in the future out into the real world and carry on with us the value of “any person, any study” for the rest of our lives.

Author’s reflection by Sofia Maslova

It was a privilege to be able to interview Soledad Chango, and I am thankful to her for her participation in our project. Our group learned so much from her, and working with these materials has expanded my understanding of the larger political and cultural implications of the languages that universities choose to offer for study. The topic of endangered languages is extremely relevant and I hope projects such as the ones showcased in Any Person, Many Stories can encourage Cornell and perhaps other universities to provide more opportunities for native speakers of endangered and minority languages to teach them.

Notes

- Lia Sokol, “Quechua language instruction returns to Cornell.” The Cornell Chronicle, November 15, 2021. https://news.cornell.edu/stories/2021/11/quechua-language-instruction-returns-cornell

- “Elementary Quechua I,” Class Roster Fall 2021, Cornell University, https://classes.cornell.edu/search/roster/FA21?q=quechua&days-type=any&crseAttrs-type=any&breadthDistr-type=any&pi=

- “Elementary Quechua II,” Class Roster Spring 2022, Cornell University, https://classes.cornell.edu/search/roster/SP22?q=quechua&days-type=any&crseAttrs-type=any&breadthDistr-type=any&pi=

- Credit: Photos provided by Mario Einuadi Center for International Studies