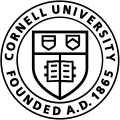

From left: Henry Arthur Callis, Charles Henry Chapman, Eugene Kinckle Jones, George Biddle Kelley, Nathaniel Allison Murray, Robert Harold Ogle and Vertner Woodson Tandy

Credit: Alpha Phi Alpha Fraternity, Inc.

“The Pride of Our Hearts”

A Short Story of Alpha Phi Alpha Fraternity

Alpha Phi Alpha, the pride of our hearts

Alpha Phi Alpha Fraternity Hymn

And loved by us dearly art thou,

We cherish thy precepts, thy banner shall we raise,

To thy glory, thy honor and renown.

Credit: Alpha Phi Alpha Fraternity, Inc.

What history gave rise to these lyrics in this hymn, emblazoned in the memory and being of the men of Alpha Phi Alpha Fraternity, Inc., the first of the organizations now known as Black Greek Letter Organizations (BGLOs)? What is the backstory that informed the aims of this organization, also enunciated in this hymn: “Manly deeds, scholarship and love for all (human)kind”? What follows is a brief attempt to excavate the soil in which the seed of Alpha Phi Alpha germinated and developed into a full flowering, sturdy, radiant plant that inspired the growth of similar but distinctive species (other BGLOs).

Following the 1904-1905 academic year at Cornell, the six African American students enrolled at the university did not return to campus in 1905-1906 “for financial and personal reasons”[1]. Another reason influencing their departure was a hostile, isolating campus racial environment. Cornell prided itself as a place where any person—irrespective of color, gender, or religious affiliation—could find any instruction in any (field of) study. Yet “for the most part, (B)lack students … were not permitted to live in campus housing or to take their meals with white students.” Thus, these students sought boarding in the homes of Black Ithaca residents far below East Hill. Charles Harris Wesley—university president, historian, clergyman, and Alpha’s longest-serving General President—wrote, “the (social) cleavage, characteristic of this period, had laid the basis for the division even in college life.”[2] [3]

Nonetheless, and perhaps for the first time in the then-40-year history of Cornell, a “critical mass,” so to speak, of 15 Black students arrived on East Hill[4]. Included in this number were five of the seven students who would become the founders of Alpha Phi Alpha Fraternity, Inc. In the lore and language of Alpha, these sable-skinned “Magnificent Seven” are known as the Jewels of the fraternity, a term likely inspired by the jeweled pin/badge of the Fraternity and Masonic iconography[5].

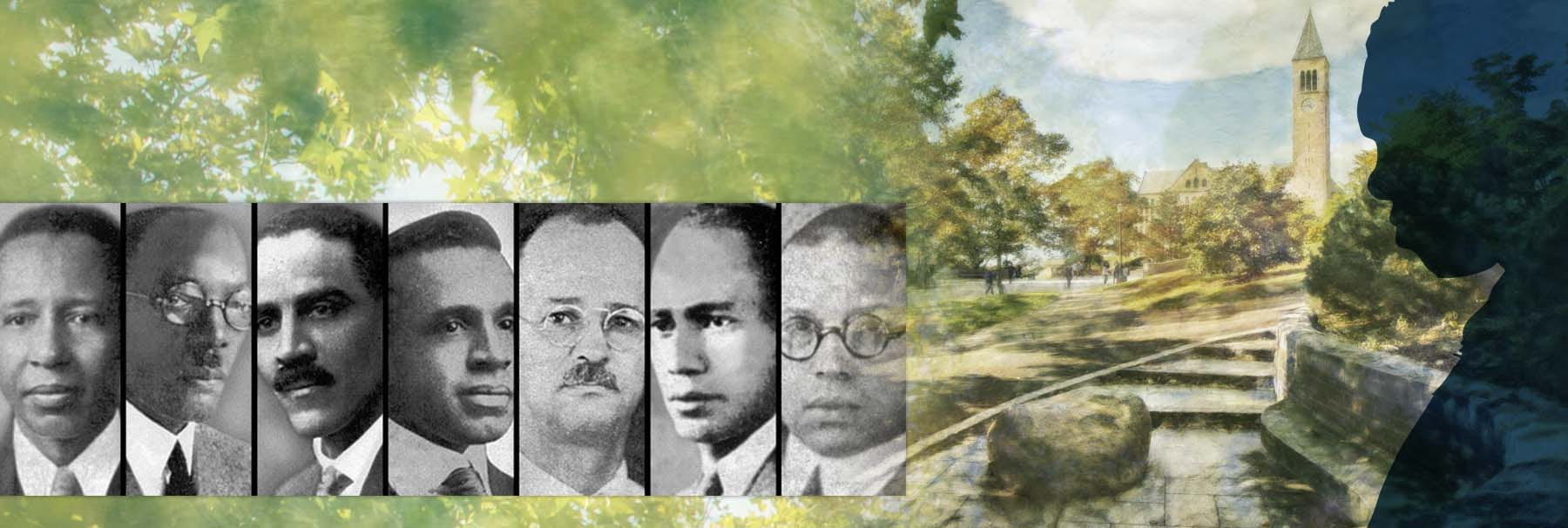

Credit: Alpha Phi Alpha records, Cornell University Library

Left image: 1906 charter for Alpha Phi Alpha

Credit: Alpha Phi Alpha wiki, Wikipedia

Middle image: The first meeting place of the Social Study Club: Mr. Edward Newton’s Residence, 421 North Albany Street, Ithaca, New York. The house owned by the Newton family still stands, but it is not safe for entry. Cosmetic repairs to the exterior in recent years have greatly improved its appearance. It was an important meeting location for the founders and other progenitors of Alpha Phi Alpha in its evolution from social study club to fraternity.

Right image: 411 E. State Street, Ithaca, New York, the home of Archie and Annie Singleton, was the meeting place of the Social Study Club and later, the first home of the Alpha Phi Alpha Fraternity. Ms. Singleton is considered the mother of the fraternity; her gravesite is in Buffalo, New York, and is periodically visited by Brothers. In a few years, a true-to-scale facsimile of the front of 411 will be erected along with historical markers and explanatory material about the site and its significance to Alpha, Ithaca, and Cornell. Ground was broken for this site in May 2022 and will correspond with the renovation of an impressive property on Winterbourne Lane, which will become the permanent fraternity house in Ithaca for Alpha.

Credit for middle and right images: Alpha Phi Alpha records, #37-4-2509. Division of Rare and Manuscript Collections, Cornell University Library. https://digital.library.cornell.edu/catalog/ss:550396

Wesley notes that the future Jewels and other Black students developed a program of study and self-support in 1905-06. “They focused on aspects of America life, the study of language and issues affecting (B)lack life in America”[6]. These students developed a prototype of student support, belonging, and community building that contemporary student services/student affairs structures in higher education seek to provide for and with vulnerable populations. Between the fall of 1905 and December 1906, the social study group morphed into a society, then a fraternity. This organizational evolution was at times fraught with heated debate. Those who wanted to remain a society clashed with those who aspired to organize a fraternity.

‘These students developed a prototype of student support, belonging, and community building that contemporary student services/student affairs structures in higher education seek to provide for and with vulnerable populations.’

Source: Wikipedia

Source: apa1906.net

Henry Arthur Callis, one of the 15 entering Cornell in 1905, envisioned a fraternity with social study programs. Known later as the “philosopher of the founders,” Callis “vociferously and eloquently affirmed the social purpose and social action that shaped the Fraternity’s origins and its ongoing mission” during its first 68 years[7]. The intersecting vision of fraternity advancing social change held by Callis—whose family frequently hosted Frederick Douglass (a relative of his mother) and Harriet Tubman—and other nascent Alphas, was most influenced by the 1905 Niagara Conference. This conference was led by future fraternity member W.E.B. DuBois. The conference issued a Manifesto of Human Rights, demanding full constitutional rights for African Americans “in a national context in which 3000 lynchings of Black people had occurred in the previous 25 years.” [8] The social and political gains of Reconstruction had all but vanished under insidious Jim Crow segregation in the South and overt discriminatory practices in the rest of the nation. The Niagara Movement was seminal to the founding of the NAACP (National Association for the Advancement of Colored People) in 1909.

It was through the alumni chapter in Ithaca that I and three distinguished gentlemen became members of the fraternity in April 2005, 31 years after I entered college.

Even as Alpha was the first continuous BGLO for college students and the first to form an alumni chapter of such, Walter Kimbrough[9] and Robert Davis—members of the fraternity—highlight in detail pre-existing fraternal orders in Black communities as early as the 18th century that informed the formation of Alpha. There were short-lived college-based fraternities or societies founded by Black collegians before December 4, 1906, Alpha’s founding date. Two years before Alpha’s founding, Sigma Pi Phi (AKA The Boule), in fact, became the first Black Greek Letter Organization, established for the Black professional class.

That said, Alpha is particularly distinguished, because as a collegiate organization it spread rapidly across the nation between 1906 and 1926, when its first 45 chapters were established. This rapid expansion also inspired the creation of other Black Greek organizations. Eight of the current 9 BGLOs (also called the Divine Nine) were founded between 1906 and 1922. Iota Phi Theta, the 9th BGLO, was founded in September 1963 at Morgan State University, my undergraduate alma mater. Hence, the origins of college-related Black Greek Letter Organizations are directly traceable to Alpha Phi Alpha, founded at Cornell.

Alpha is particularly distinguished, because as a collegiate organization it spread rapidly across the nation between 1906 and 1926, when its first 45 chapters were established. This rapid expansion also inspired the creation of other Black Greek organizations.

Historical Context

Alpha and the other BGLOs were founded during periods of intensified resistance to racism and hostile racist backlash in American society. Rayford Logan, noted historian and a past General President of Alpha, described the period in which eight of the nine organizations were created as the nadir: the low point in African American history. Iota Phi Theta was founded four days following the horrific bombing of the Sixteenth Street Baptist Church in Birmingham, Alabama, that killed four young Black girls. This tragedy occurred less than a month after the historic March on Washington for Jobs and Freedom, attracting over 250,000 people (including my late mother, who participated with her union of International Ladies Garment Workers).

Given that nexus of organizational origin and social struggle, it is no surprise that many luminaries of the 20th and 21st century Black freedom struggle were also members of Black fraternities and sororities. Among those were Alphas such as DuBois, mentioned earlier; Jesse Owens, whose four gold medals won at the 1936 Berlin Olympics demolished the Nazi myth of Aryan superiority; Hamilton Holmes, who with the journalist Charlayne Hunter-Gault (a member of Delta Sigma Theta Sorority), desegregated the University of Georgia; Leo Hansberry, Howard University scholar who paved the intellectual path for Africana Studies as an academic discipline and uncle of playwright Lorraine Hansberry; Paul Robeson, legendary activist/singer/actor/intellectual; Martin Luther King, Jr.; Edward Brooke, who in 1966 became the first Black U.S. Senator elected since Reconstruction; Rev. Dr. William Barber, co-leader of the current Poor People’s Campaign modeled after the original 1968 campaign initiated by Dr. King; Jelani Cobb, Dean of the Columbia Journalism School; Rev. Dr. Frederick D. Haynes III, Dallas, Texas-based pastor and activist; and many more.

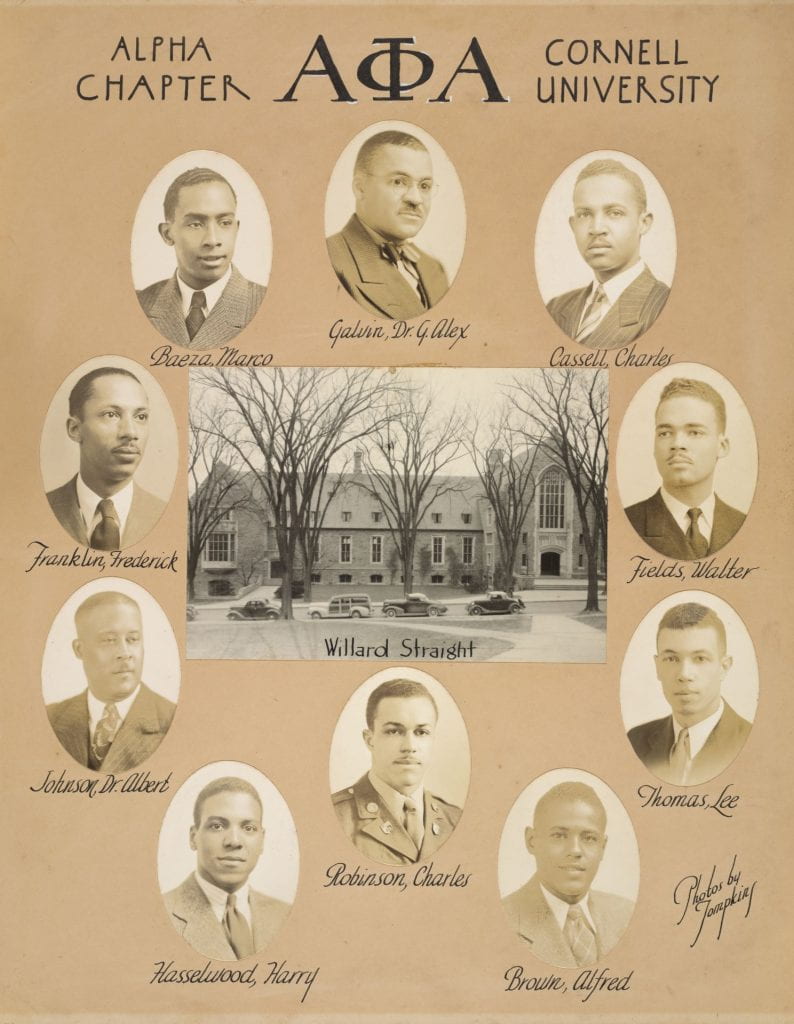

Credit: Galvin family papers, #4933. Division of Rare and Manuscript Collections, Cornell University Library

Alpha and the other BGLOs were founded during periods of intensified resistance to racism and hostile racist backlash in American society.

Personal Impact

Members of Alpha have been profoundly influential to my spiritual, vocational, intellectual, and professional development from the advent of my young adult years to the present. I have been blessed to have been mentored by two Alpha men who themselves were mentored by Dr. King and embodied the nexus of fraternity, social action, and spirituality.

Credit: Karen Jackson, The Baltimore Sun

After finishing my undergraduate requirements at Morgan State University—a historically Black institution—in Baltimore during the summer of 1979, I became a member of the city’s New Shiloh Baptist Church. New Shiloh’s pastor, Rev. Dr. Harold A. Carter, had been a student ministerial assistant to Dr. King during the 1955-56 Montgomery, Alabama Bus Boycott, in which he participated. The Boycott occurred when Dr. Carter was a senior at Alabama State College (now University) in Montgomery, located a short distance from Dexter Avenue Baptist Church where Dr. King was pastor. Dr. King participated in Dr. Carter’s initiation into the fraternity and encouraged him to apply to Crozer Theological Seminary in Chester, Pennsylvania from where Dr. King graduated in 1951, to prepare for ministry.

Dr. Carter graduated from Crozer in 1959 and became active in the Civil Rights Movement during pastorates in Lynchburg, Virginia, and Baltimore. In the late 1960s, he led the Baltimore chapter of Operation Breadbasket, a program of Dr. King’s Southern Christian Leadership Conference which used, “the persuasive power of black ministers and the organizing strength of the churches to create economic opportunities in black communities.”[10] During his 48-year ministry at New Shiloh, he was one of the city’s most prominent clergypersons and a nationally and internationally sought-after preacher and teacher.

Under Dr. Carter’s leadership and mentorship, I began to discern within myself a call to ministry, a deep inner urging to serve God and humanity through this vocation. Dr. Carter wrote a letter of recommendation for my application to what is now Colgate Rochester Crozer Divinity School (Crozer merged with then-Colgate Rochester Divinity School/Bexley Hall in 1970) in Rochester, NY, from which I graduated in 1986.

While in divinity school in 1984, I met two new incoming students: Rev. Anthony Trufant, now pastor of the now 4,000-plus member Emmanuel Baptist Church in Brooklyn, and his roommate, Rev. William Gipson, currently Special Advisor to the Vice President for Social Equity and Community at the University of Pennsylvania. We became fast friends and have remained close to this day. They too were Alphas. It was Anthony who recommended me to his uncle, Rev. Dr. Amos C. Brown, pastor of the historic Third Baptist Church of San Francisco, for a position with the church’s Ethiopian Refugee Resettlement Project following my graduation. I began working at Third Baptist in February 1987 as the director of development for the project, pursuing grants from foundations and corporations to support the resettlement of Ethiopians who fled a brutal regime to various locations worldwide and sought relocation in San Francisco. Eight months later I became assistant pastor of Third Baptist, serving in that role until August 1990.

Credit: Pax Ahimsa Gethen

Dr. Amos Brown—as you likely anticipated—is also an Alpha. For nearly 70 of his 81 years (46 as pastor of Third Baptist), he has been a church-based civil and human rights activist. As a teenager he worked with Medgar Evers, the legendary field secretary of the NAACP in Mississippi. In 1956, at age 15, he traveled with Evers to the NAACP’s annual convention in San Francisco. At Third Baptist, one of the convention’s hosting venues, he met Dr. King for the first time—20 years before becoming the church’s pastor.

As a student at Morehouse College, Dr. Brown became active in the Atlanta Student Movement, engaged in sit-ins, wade-ins, and pray-ins to desegregate public and other accommodations. He was twice jailed with Dr. King. He and seven other Morehouse students were enrolled in the only college course Dr. King ever taught in 1961-62. Two years later Dr. King wrote a letter of recommendation for Dr. Brown to attend Crozer, from which he graduated in 1968.

While attending to the pastoral and administrative needs of Third Baptist, I also participated with Dr. Brown in protests against statewide budget cuts to higher education in Sacramento; provided administrative and logistical support to an award-winning after school tutoring program, Back on Track (jointly sponsored by the church and Temple Emanu-El, the city’s influential Reform Jewish temple) and the church’s Charles A. Tindley Music Academy, programs aimed at addressing gaps in public education; was involved in the preparation for Rev. Jesse Jackson’s speaking engagement at the church during his 1988 run for the U.S. Presidency; and was a member of the Northern California Mandela Reception Committee co-chaired by Dr. Brown in anticipation of Nelson Mandela’s June 1990 rally at the Oakland-Alameda County Coliseum.

Drs. Carter and Brown have been two of the most influential figures in my development as a minister, educator, activist, and human being. They are in league with other Alphas who were instrumental to my transition into higher education at Penn State and my work at Cornell. Each of these men embodied the aims of the fraternity; were dedicated to serving others; and held in high esteem by their peers and their communities. They each were influential in my decision to join Alpha Phi Alpha. Through their example, mentorship and/or friendship they embodied the reasons why this organization is “the pride of our hearts.”

Top right: The members of Alpha Phi Alpha who made a pilgrimage to Cornell, along with community members, on Nov. 19, 2005 in Sage Chapel.

Bottom right: Cornell University Alpha Phi Alpha Centennial Memorial bench with McGraw tower in the background

Credit: Jason Koski, Cornell University

Author’s Biography

Rev. Dr. Kenneth I. Clarke, Sr., Director of the Tompkins County Office of Human Rights, was director of Cornell United Religious Work from 2001-2017. He is a member of the Iota Iota Lambda Chapter of Alpha Phi Alpha in Ithaca and serves as its chaplain. Dr. Clarke wrote and led the Litany of Rededication for the fraternity for its Centennial Pilgrimage at Cornell on November 19, 2005. He was preacher for the ecumenical service of the New York Association of Chapters of Alpha (NYACOA) annual meeting at Cornell in December 2006, which closed the year-long Centennial Celebration. Ken has also preached regularly for Alpha Leadership Academy for undergraduate fraternity leaders at Johns Hopkins University since 2012. He is a co-author of chapters on faith and fraternalism and the Alpha identity in two books focused on Black Greek Letter Organizations.

Credit: Yolanda Clarke

Notes

[1] Bradley, Stefan M. 2012. “Progenitors of Progress: A Brief History of the Jewels of Alpha Phi Alpha.” In Alpha Phi Alpha: A Legacy of Greatness, the Demands of Transcendence, by Editors Gregory S. Parks and Stefan A. Bradley, 72. Lexington, KY: The University Press of Kentucky.

[2] Armfield, Felix L., Stefan M. Bradley, Kenneth I. Clarke, Sr., Gregory S. Parks and Jeremy M. Harp. 2012. “Defining the Alpha Identity.” In Alpha Phi Alpha: A Legacy of Greatness, The Demands of Transcendence, by Editors Gregory S. Parks and Stefan M. Bradley, 42. Lexington, KY: The University Press of Kentucky.

[3] For further explication of the early 20th Century racial climate at Cornell, see Carol Kammen, Part and Apart: The Black Experience at Cornell, 1865-1945 (Ithaca, NY: Cornell University Libraries, 2009).

[4] Davis, Robert S. 2018. Ascendant: The History of the Alpha Chapter of Alpha Phi Alpha Fraternity, Inc. Washington, D.C.: Uppermost Publishing House, LLC.

[5] Armfield, Felix L, et al. 2012.

[6] Clarke, Sr., Kenneth I. 2006. “Revisiting Our Roots in the Centennial Era.” The Sphinx: Official Organ of the Alpha Phi Alpha Fraternity, Inc, Fall/Winter: 132.

[7] Clarke, S. K. 2006.

[8] Armfield, Felix L, et al. 2012, cited in Clarke, S. K. 2006.

[9] Kimbrough, Walter M. 2003. Black Greek 101: The Culture, Customs and Challenges of Black Fraternities and Sororities. Madison, NJ: Farleigh Dickinson University Press.

[10] The Martin Luther King, Jr. Education and Research Institute, Stanford University. n.d. Accessed October 1, 2022. https://kinginstitute.stanford.edu/encyclopedia/operation-breadbasket.