From Ladies’ Home Journal to Title IX: Women Graduate Students at Cornell, 1958-1962

Mary Frann (Somers) Heidhues, PhD ’65 and Ruth (Miskovsky) Mahr, PhD ’66

The “in-between” generation and Cornell in 1958

We were the “in-between” generation: women who grew up in a post-war Ladies’ Home Journal/Ozzie and Harriet culture—a culture that defined “the successful woman” as homemaker, dutiful wife, mother, consumer (and almost always white, middle class, suburban). This was the ’50s: a world dominated by men in which a woman’s role was subservient to that of her productive husband—a world divided into “bread-winning men and hearth-keeping women,” as fellow Cornellian Ruth Bader Ginsburg ’54 said, reflecting, during Cornell’s sesquicentennial year1.

Ours is the story of a group of women who eschewed conventional ’50s ideas about the role of women. Determined to take our places in the professions, we enrolled in The Graduate School at Cornell in 1958—five years before Betty Friedan’s Feminine Mystique exposed the fiction of that smiling housewife. And, degrees in hand, we left Cornell in the ’60s, before the women’s movement—with an able assist from Title IX—succeeded in replacing that ’50s stereotype with a new vision: one in which women would participate more equally and inclusively in the life of society.

[The world was divided into]

Ruth Bader Ginsburg

bread-winning men

and hearth-keeping women.

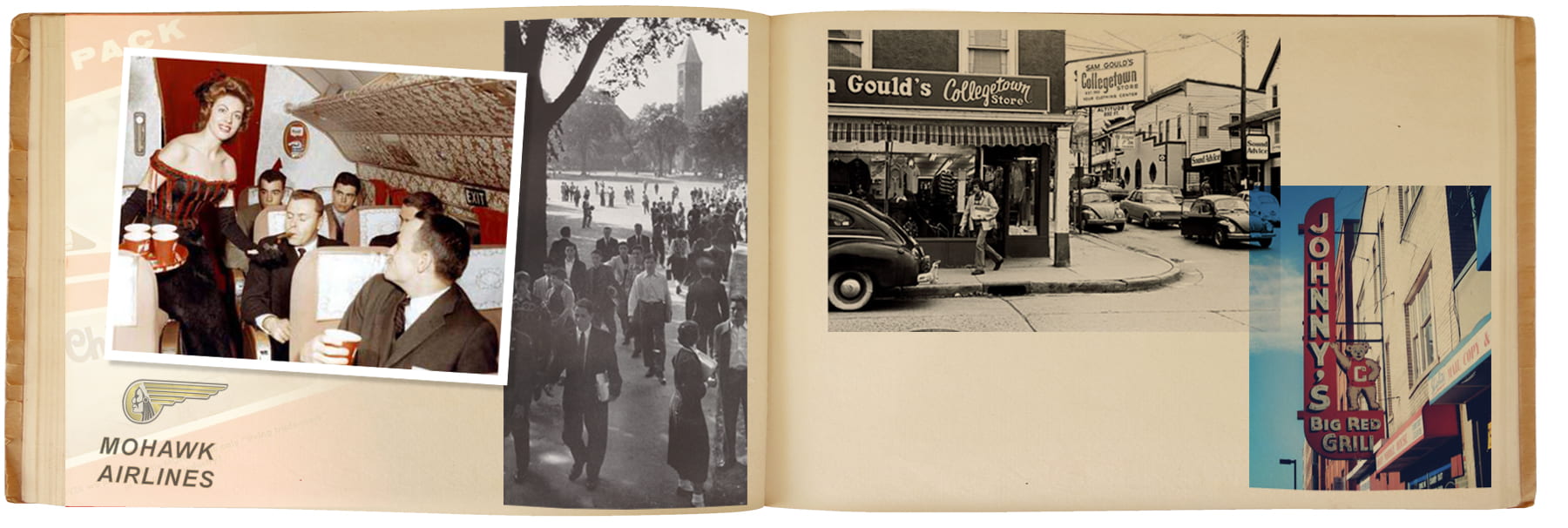

We arrived at Cornell in the pre-mall, pre-urban-sprawl, late ’50s. Downtown Ithaca sported three department stores, of which one was locally owned, as well as, among others, shoe stores, florists, the Ithaca Hotel, and three movie theaters. (A typical weekend date in 1958 consisted of a movie—preferably at the State Theatre, where your date steered you to the back row of the capacious balcony—followed by a hamburger at Obie’s diner in the west-end.) Church steeples dotted the landscape; factories employed blue-collar workers, many of whom lived in the Fall Creek neighborhood; and the Clinton House (now home to New Roots School) served Sunday brunch on white linen tablecloths to townspeople emerging with hats and white gloves from Sunday church services. The Lehigh Valley railroad still passed through Ithaca with service to Buffalo and New York City. Famously, Mohawk Airlines would soon initiate its men-only Gaslight Service from New York City to Ithaca.

Right: Gould’s and Johnny’s were Collegetown landmarks for decades. Credits: Tompkins Weekly’s East Hill Notes, courtesy of The History Center in Tompkins County (top left); Mark H. Anbinder ’89 (bottom right)

Collegetown was anchored, at the corner of College and Oak Avenues, by Pop’s Place, where the food was decent and, above all, cheap, and, opposite it, on College Avenue, Triangle Book Store (offering an alternative to the Campus Store, then situated in Barnes Hall). Around the corner, on Dryden Road, two prominent landmarks prevailed: the Royal Palms and Johnny’s Big Red Grill.

Cornell in 1958 was deeply ensconced in the culture of gender conformity—the ’50s “on steroids.” Despite its more egalitarian roots, embedded in Ezra Cornell’s commitment to equal educational opportunities for women, the university was predominantly a male institution—run by men for men.

Thanks to an 1884 resolution requiring all women undergraduates to live on campus, combined with the university’s failure to expand at a faster rate the number of beds to accommodate them, for decades—and continuing through the ’50s (with the exception of World War II)—the number of female students enrolled did not exceed 25 percent of total enrollment. In the late 50s, when we arrived, total enrollment was around 8,000 students, of whom 2,000 were women.2 Women undergraduates were a protected class, subject to various restrictions like curfews; furthermore, living on campus in dormitories or sororities made them a captive audience for instruction in the art of “gracious living.”3

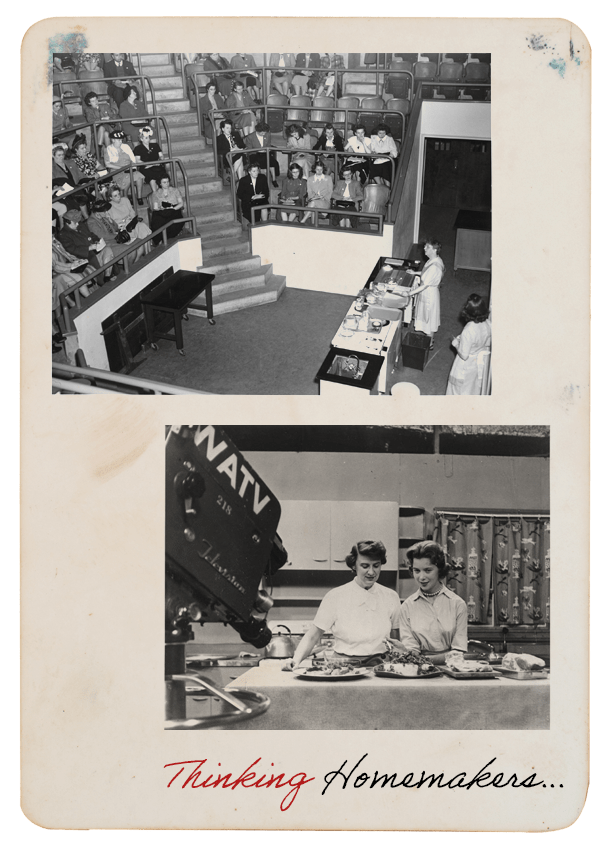

Opportunities for undergraduate women—in both academics and extracurricular activities—were distinctly unequal to those of men. Perhaps nowhere was the disparity as glaring as in athletics: limited gym space, lockers, showers, and an athletics budget in which, as late as 1971-72, allocations for women’s sports were less than 4% of the total university allocation to intercollegiate athletics.4 But discrimination abounded in other places as well: for example, the marching band excluded women (which remained all-male until 1970), and the Cornell Daily Sun had only limited openings for women.5,6 Compounding the disparity in admissions’ practices between men and women, those few beds that were available for women were apportioned by the university to the various colleges, primarily Arts and Sciences and Home Economics, where, in 1959, the Dean proclaimed that the goal of the college was to produce “thinking homemakers.”7, 8, 9 In that same year, 1959, a proposal to increase the number of women admitted to the College of Arts and Sciences was rejected by the Director of Admissions on the grounds that it would be deleterious to the university endowment as well as to Cornell’s reputation and ability to compete with exclusively male institutions in attracting male students. The College would suffer a loss of prestige if it were to become known as less of a “men’s college” and more of a “‘women’s’ college with men students.”10

As a result of discriminatory enrollment, education, and hiring practices, the Cornell campus in the ’50s reflected the power structure of the larger society. Outside of Home Economics, there were few, or no, professional women to serve as mentors and role models for women students; there were virtually zero places for women in the professional schools; and restrictions on the number of women in Arts and Sciences meant that fewer women were being prepared with the broader knowledge that would be helpful in professions like law or medicine and essential for women in academia. Cornell did little or nothing to disabuse students of preconceived notions of the role of women in the professions. Instead, the paucity of women on the faculty (outside of Home Economics), their absence in higher levels of administration, and their exclusion as students in the professional schools served only to reinforce—for all students, male and female—the prevailing cultural understanding of the role of women in society, namely that positions in leadership and in the professions belonged—rightfully—to men.

—for all students, male and female—the prevailing cultural understanding of the role of women in society, namely that positions in leadership and in the professions belonged—rightfully—to men.

As graduate students, we may have been largely oblivious to conditions for undergraduates, but we could not help noticing the male-dominated milieu in which we functioned. We can recall few female faculty members in our respective departments. Faculty wives mirrored conventional expectations for women, organizing teas and parties and not working outside the home. In all, the culture was male dominated, “old-school,” stiff and formal.

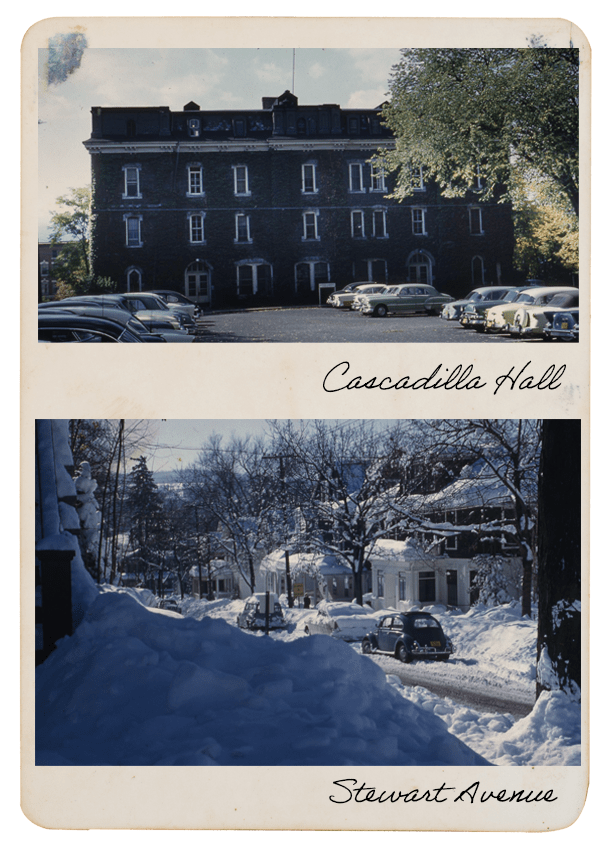

Establishing an Apartment, Building Community: The 114 Experience

Finding a Place for Six

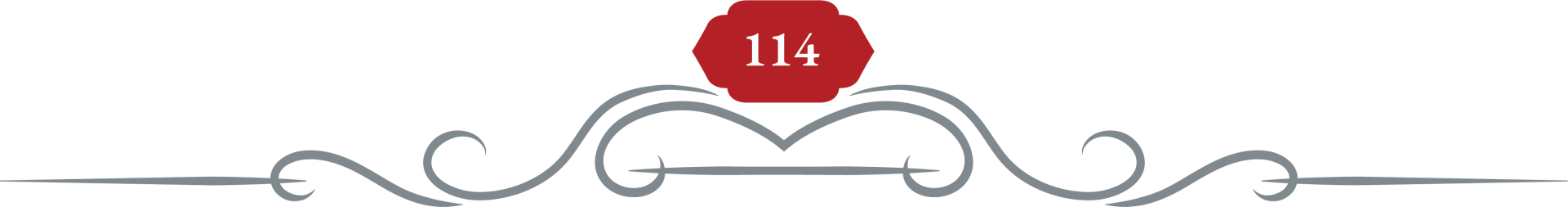

Despite its shortcomings, the graduate dorm, Cascadilla Hall, where all of us who arrived in 1958 lived, was a good place to meet other graduate students. By spring semester of that first year, our acquaintances had grown beyond roommates and chance encounters in the halls, and Kathleen, Hannah, Connie, E-Wa, Ruth, and Mary Frann began to discuss the possibility of rooming together. Thus began the search for an appropriately spacious apartment for six women. Finally, at 114 Stewart Avenue, we encountered a local couple who lived on-site and who were eager to rent the upper two floors of their frame house to female students, presumably under the misguided belief that women would be good tenants—i.e. quiet and fastidious.

114 Established

Of those who lived at 114, some were Americans of Jewish, Irish, and Czech backgrounds, some with immigrant parents. Others were German, Dutch, Chinese, English/Australian, Anglo-Irish, and Korean. In addition to bringing cultural diversity (including and especially ethnic food) to the enterprise, 114ers enjoyed a rich social life through connections to students in their various departments (government, chemistry, biochemistry, economics, history, nutrition, food science, and horticulture).

Out of diversity we built an inclusive community as well as friendships that continue to this day. Fundamental to the success of the 114 enterprise was a set of rules for the co-operative management of the enterprise; the kitchen, which served as the communal meeting space; the camaraderie we were able to develop through shared interests and activities; and the emotional support we offered one another.

Organization, Rules

Founding organizational rules supported a well-run, co-operative living arrangement (dubbed by some a commune) with chores carefully delineated and rigorously administered. In the first summer Connie, a Home Economics graduate working on a Master’s in Nutrition, defined three general chore areas: cooking and shopping, cleaning up after meals, and cleaning the common areas. Two women partnered to handle each chore area; chores rotated every week, as did partners. Food made the most work. The cooking partners used Connie’s car, and later Ruth’s, to visit the A & P every week, loading six large bags of supplies for meals, including do-it-yourself breakfasts and sandwiches for brown bag lunches, which were packed by the cooks in the evening. If a roommate had an important exam or other challenge coming up, she could trade tasks. It worked surprisingly smoothly, despite the turnover of residents.

Connie’s rigidly egalitarian system certainly helped maintain good interpersonal relations. Simple rules assured not only that basic tasks would be done, but that they would be done cooperatively, and this ensured the well-being of the common enterprise. We each contributed, apart from individual rents, ten dollars a week for common expenses, i.e. food. Unbelievably, it usually sufficed.

The Kitchen

The big, bright kitchen soon became the meeting place and focal point of the group. Usually all of us came for dinner every evening, even if we sometimes returned to lab or library afterward. The less practiced cooks soon developed new skills. Among the memories, that of the new varieties of foods remains strong. Over the years, we ate stir-fried beef and vegetables (with chopsticks, naturally), Maureen’s Yorkshire pudding and trifle, A-Young’s kimchi and bulgogi, Czech apricot dumplings from Ruth, and a variety of other choices. Rice was more common than potatoes; Kathleen taught us to drink tea with milk. Jane, with an aversion to turnips since her wartime school menus in England, remembers looking forward to the weeks when Ina, from the Netherlands, was “on” for cooking, as it meant Dutch cheese and real hot chocolate for breakfast! Needless to say, turnips were never on the menu. Karin caused a small revolution when she asked us to (finally) replace margarine with butter.

Rice was more common than potatoes; Kathleen taught us to drink tea with milk...

Special occasions, like visitors for dinner, holidays, or celebrating a passing grade on an exam merited a bottle of wine. Empty bottles served as memories of these occasions and were placed atop the kitchen cabinets. The bottle collection would soon become a special feature of our kitchen. At the dissolution of the apartment in 1962 the entire collection surreptitiously ended up in Ruth’s honeymoon getaway car.

Although dinner was a focal point, the kitchen was always available for snacking, or for making a cup of tea, reading the paper, listening to the radio, or for consultations of all kinds. Often, it was an antidote to unsatisfactory interactions with difficult professors or uncooperative fellow-students or simply frustration over the progress of our work.

Friendships and Camaraderie, Social Life

The experience of being women graduate students combined with that of living and working together to maintain our communal space assured a certain level of camaraderie among 114 residents. Bonds were strengthened by shared interests. Importantly, among us and the friends we introduced to 114 was a strong contingent of event planners. Parties and especially outdoor activities, to which all 114ers were invited, further promoted a sense of cohesion and friendship.

Music turned out to be a shared interest among several of us. Hannah and E-Wa had a subscription to the concert series, and E-Wa played the recorder (as did Karin). Hannah’s father, who loved classical music, frequently shared his favorite LPs with her. Hannah would initiate us into a new Mozart or Dvorak, reading the cover text aloud. With the definition of music extending to music for dancing and social critique, jazz—especially Dixieland—and folk music soon began expanding our record library. Friends lent us new recordings, with Joan Baez, Louis Armstrong, Bob Dylan, Pete Seeger, the Weavers, Dave Brubeck, and Tom Lehrer.

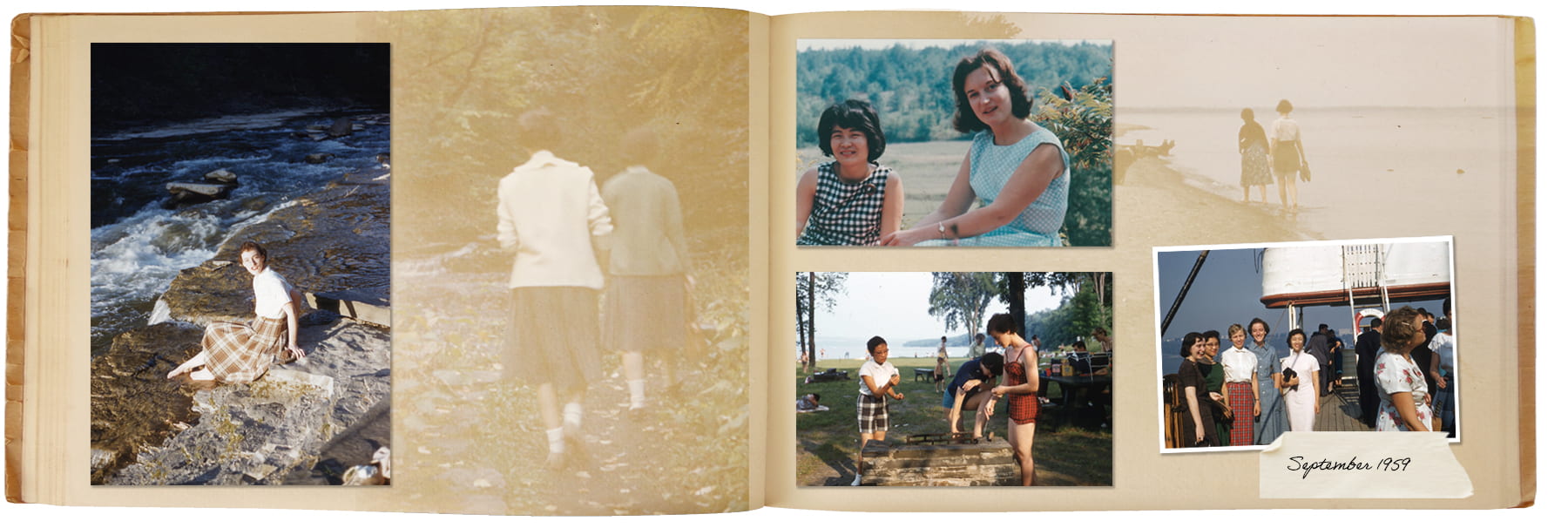

Inevitably, there were outdoor activities, picnics, swimming, hiking, camping excursions in summer, skiing and skating in winter. Three friends lived on a farm outside of town, where some of us picnicked or swam in the pond, and (in 1961) celebrated New Year’s Eve, returning to Ithaca in a snowstorm.

Dinner guests were frequent and welcome: colleagues, potential roommates, potential mates, families of co-workers, even visiting friends or parents. All were welcome. One later asked, “Do you girls still eat so much food?” For the record: no one gained weight. One or two climbs up The Hill every day were more than enough to burn any excess calories.

“Do you girls still eat so much food?”

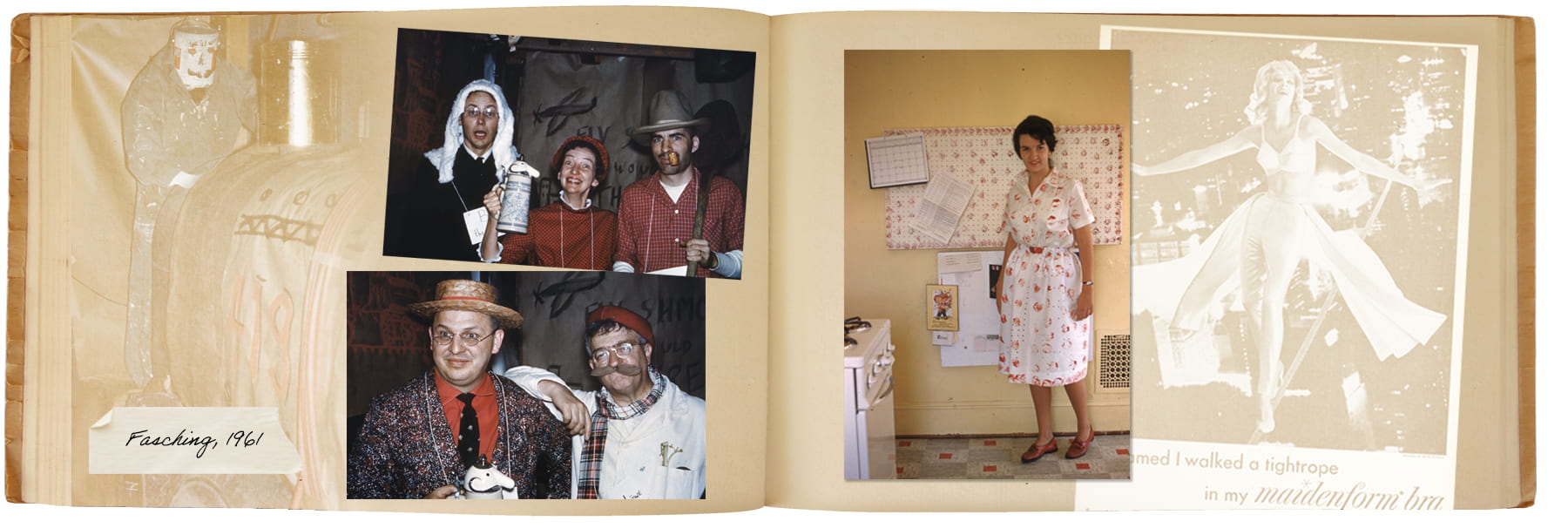

And there were parties. 114’s partying reflected the group’s diversity; we celebrated not only traditional American festivals such as the 4th of July and Thanksgiving, but, thanks to our German friends, we also participated with enthusiasm in Fasching, the southern German version of Mardi Gras, working for days on fanciful costumes for the 1961 party. One of our roommates, inspired by advertising, called her costume, “I dreamed I went to Fasching in my Maidenform bra.”

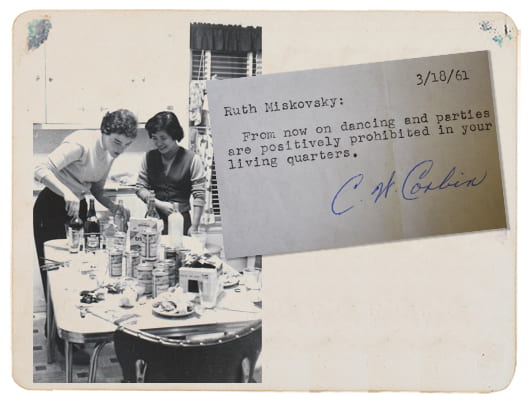

One day, believing that our landlords were away for the evening, 114 became the site of an impromptu party. Beer arrived as if by magic; dancers piled into the kitchen, bouncing to “Tiger Rag”; candles swayed—until our landlords, who lived downstairs, unexpectedly returned to their quiet home, only to find it rocking. Ruth’s efforts at negotiating a peace accord with our landlords that would include some “quiet” parties were summarily dismissed. There would be no more parties.

Support

Graduate study was, inevitably, often stressful. The chemists and biochemists among us had an especially hard time—experiments flopped, solutions spilled, delicate but necessary apparatuses broke down and repairs meant unwelcome delays. Our nutritionist, Connie, fed and weighed lab rats—they bit her when she handled them; she developed an allergy to the beasts. Kathleen, the historian, squinted over fuzzy microfilms until she finally asked for another topic for her MA thesis. Her professor, who was not shy about letting her know that, as a woman and a Master’s candidate, his expectations of her were not terribly high, assigned her, a lifelong city girl, to a long-term study of changes in agriculture in upstate New York.

The biochemists, who worked at close quarters with a temperamental professor, actually conferred with others in their lab every morning to determine what his mood might be that day. On some days, he displayed a tendency to bully, our roommate often being the target. We shared sympathy, consolation, encouragement. Along the way, we also learned a lot about subjects other than our own.

Misogyny sometimes surfaced, as when some professors expressed disdain for women grad students (a government professor referring to a woman who had successfully defended her excellent dissertation, “She didn’t even know there were two houses of Congress when she came here.”). When Ruth’s professor invited her to lunch after her return from her year in Germany as a Fulbright scholar, they were not allowed to eat at the Rathskeller in the Statler. Although the Rathskeller had been “integrated” in 1958, the largesse did not extend to female graduate students.

114 as an institution dissolved at summer’s end in 1962. By then, some of the initial members had finished their Master’s degrees and moved relatively smoothly into the job market. Five of us, including three of the founding members, completed PhDs in the years between 1963 and 1967, another one several years later. All of us had married by the end of the decade, and nearly all had had children. All viewed their husbands’ careers as primary and settled wherever it was that their husbands’ careers took them. For two of us, who had married Cornell faculty members, Ithaca would remain home.

Aftermath

When we finished graduate work at Cornell, Title IX was still some years off; the women’s movement had not yet taken flight; and the cultural expectations of the ’50s were still largely operative. Professional women seeking employment continued to meet strong headwinds in their fields. Not only was it possible for professional women to face a hostile job market, but traditional attitudes about women’s role in child rearing and the lack of social support institutions like daycare combined to dampen professional ambitions.

Professional women seeking employment continued to meet strong headwinds in their fields.

Our “success” as professionals would be quite mixed. What we were able to accomplish professionally depended upon a number of factors, including individual priorities relative to family and work; flexibility of our partners’ work schedules; ability to find and hire help with childcare and household tasks; and demand for our talents and abilities in the job market where we lived, especially as influenced by attitudes toward women as professionals.

Those 114 residents who sought Master’s Degrees in an applied field like nutrition, or who wished to teach at the secondary level, or to seek work as librarians, all of which were generally identified as “women’s” professions, would find work easily. Two bio- chemists were able to build successful professional careers—one in the patent department of a pharmaceutical company; the other as a research scientist dependent upon federal grant money. Both had assistance with household help and childcare. Two chemists were unable to find work in their fields and ultimately gave up; one later contributed significantly to Ithaca´s music scene. Another of our 114 residents looks back on a professional trajectory that was “mixed and broken by long periods in Southeast Asia,” finally “combining writing, editing and research with some fifteen years of social service spent resettling mainly Asian refugees” whose culture and language she had studied at Cornell. The authors of this story ended up living in small academic cities where we faced challenging local job markets. We have decided each to tell her own story to illuminate both the obstacles and how each of us dealt with the challenges we faced.

Reunions

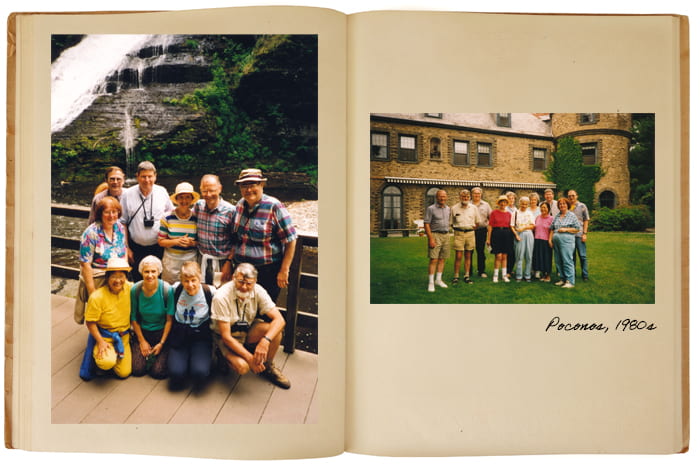

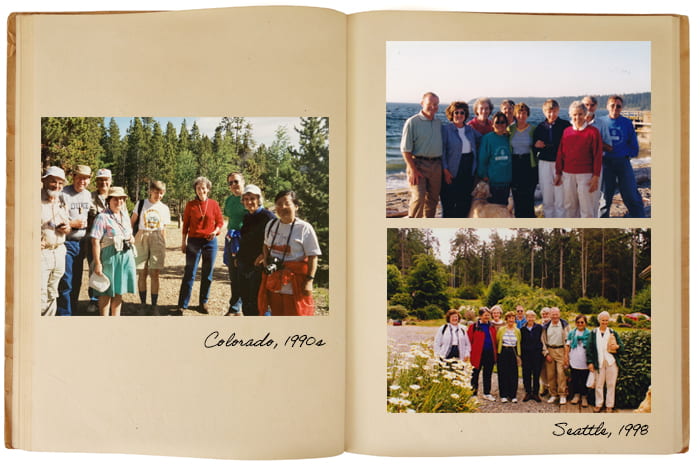

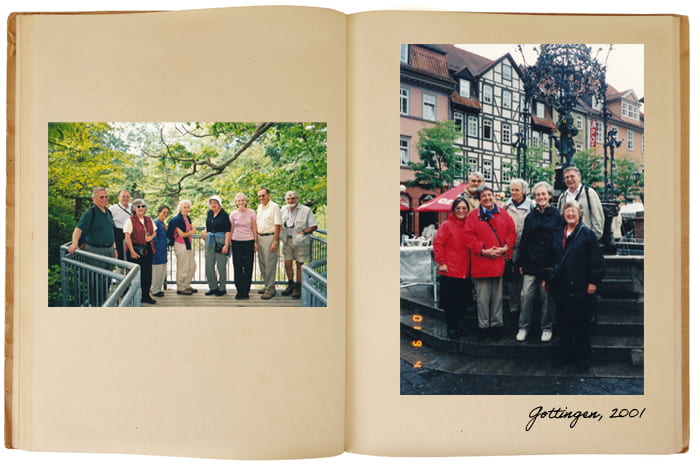

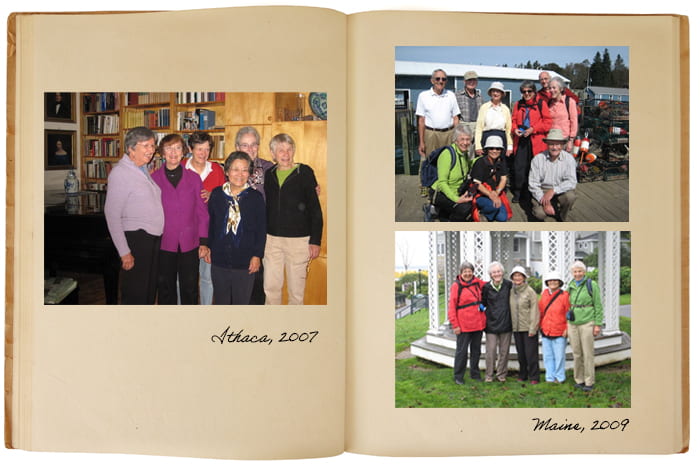

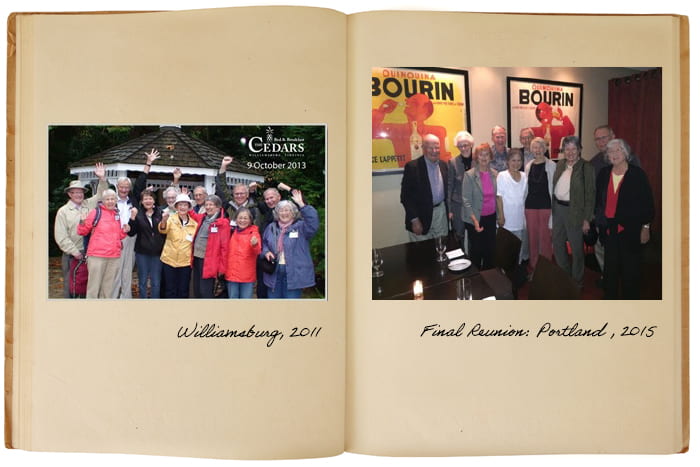

The 114 story did not, however, end in 1962 with the dissolution of communal living at 114 Stewart Avenue. Over the years, we have maintained friendships through visits, letters, and a series of reunions to which spouses were always gladly welcomed.

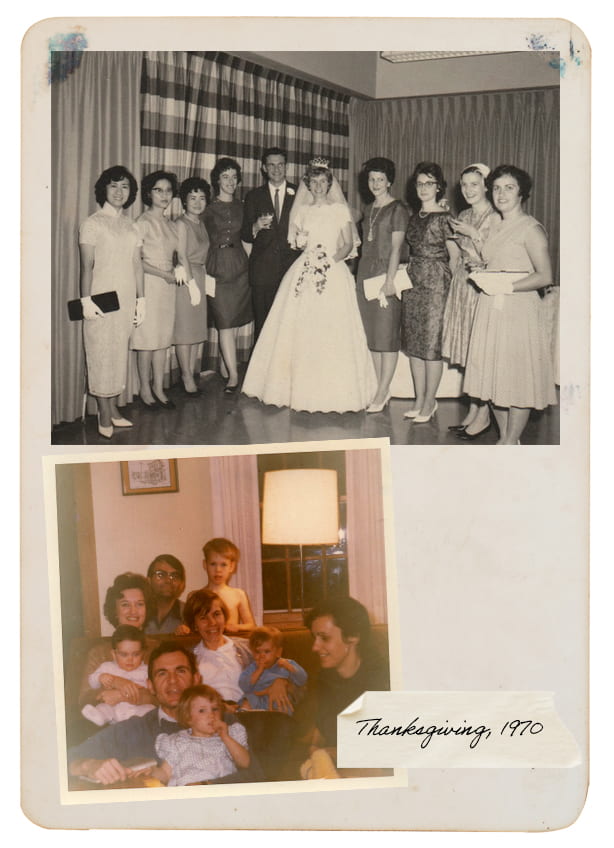

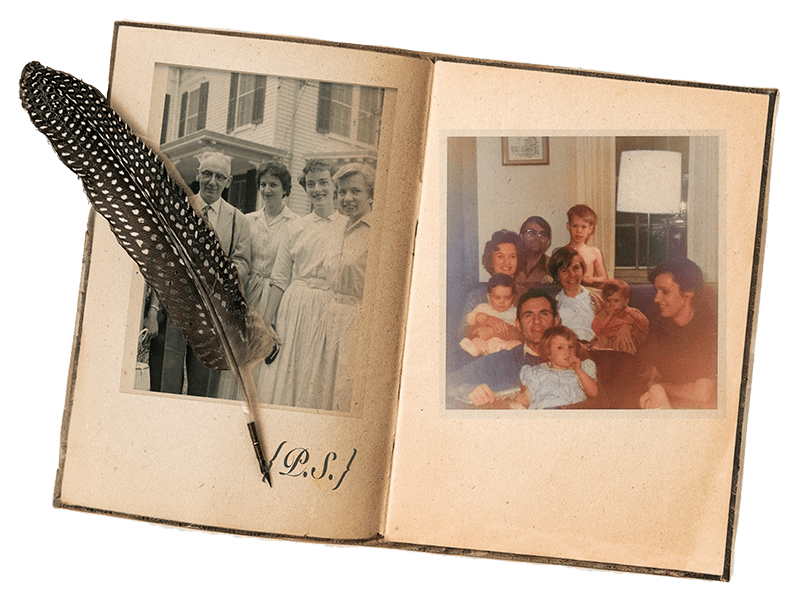

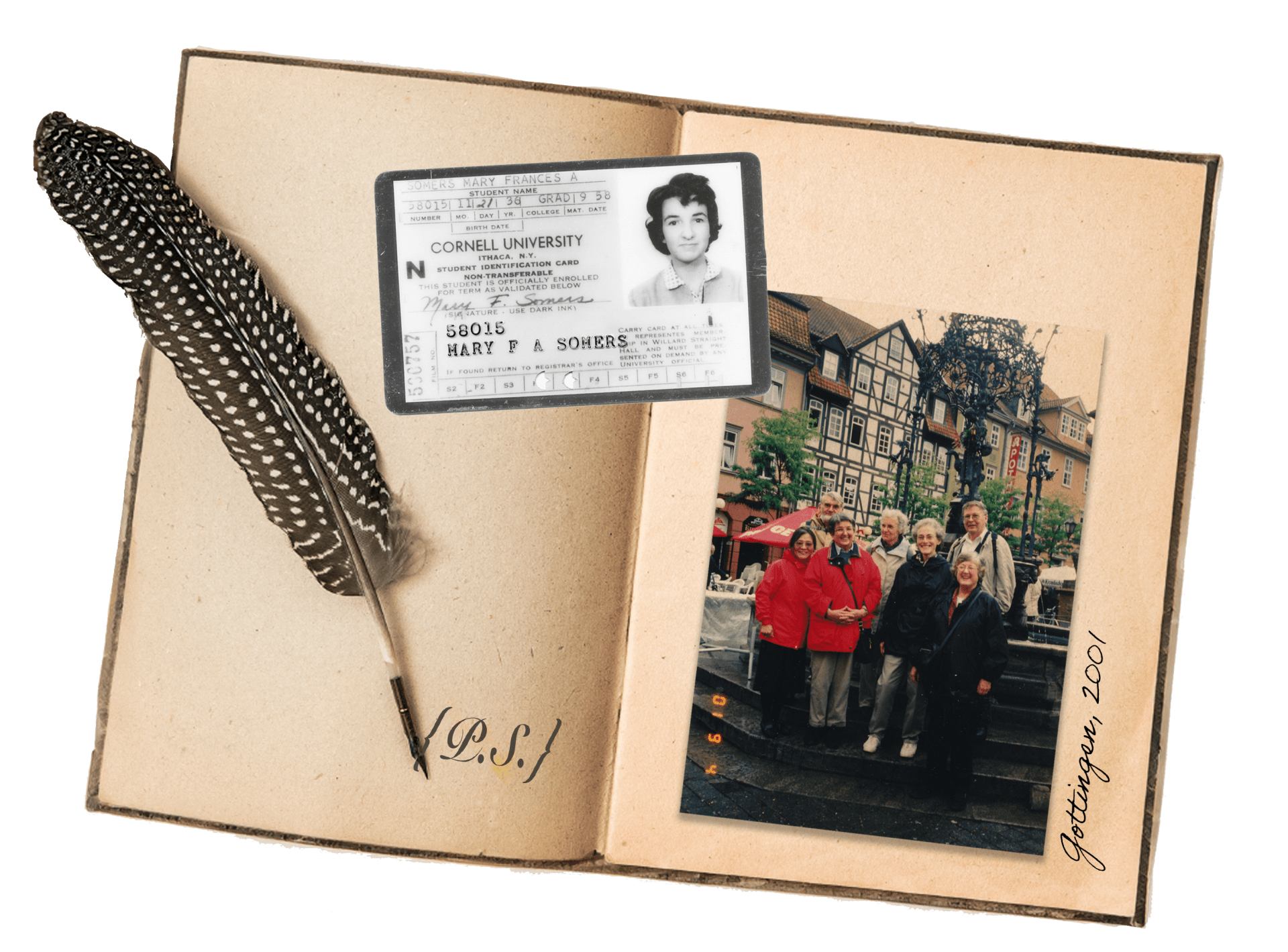

The first of our reunions was a somewhat impromptu affair in 1970. Several of us descended with husbands and children upon Mary Frann’s parents’ house in Washington DC to see Mary Frann, who had returned with her family from Germany. We met again in Ithaca in the ’80s. Thereafter, the idea having gained momentum, we began to reunite regularly—usually every two years, often where one of us lived—be it Seattle, WA or Göttingen, Germany—but occasionally elsewhere, like Williamsburg, VA and Acadia National Park. Our final in-person reunion took place in 2015 in Portland, OR, after which mobility issues became prohibitive.

The advent of Zoom, though, has enabled us to resume meeting virtually, and while, sadly, our numbers have diminished, six of us continue to meet virtually several times a year.

The accompanying selection of reunion photos reflects both our aging and our enduring ties over the years. For us, “114” will always stand for those friendships that began many years ago among a group of women graduate students at Cornell who shared the singular experience of communal living at 114 Stewart Avenue.

Postscript from Ruth

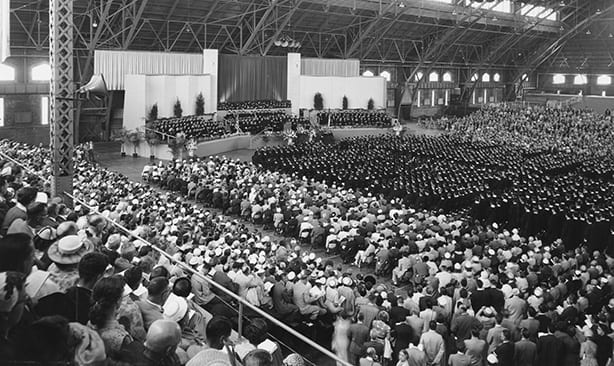

In 1966, I donned cap and gown and marched from the Arts Quad to Barton Hall, where I walked across the podium, shook hands with Provost Corson, and became officially Doctor of Philosophy in Economics. I was by this time also the wife of a Cornell faculty member, mother of a one-year-old, and an Ithaca resident. In terms of developing a career, potential employment in my field would be confined to those limited opportunities available in the Ithaca area.

The Economics Department of the late ’50s at Cornell was not a strong department. With one notable exception, professors were little engaged in research and had few connections outside of Cornell. They were old-school academics in an age when economics as a discipline had not yet become research oriented and “science” driven. I’d had little or no training in research methods. There would be limited outlet for my academic training in Ithaca aside from teaching.

I loved teaching. (As graduate students we’d had plenty of teaching experience—we earned our way teaching introductory economics). Teaching was, for me, a little like acting—delivering soliloquies before captive audiences, with a good dash of audience participation thrown in.

But women seeking teaching positions at Cornell in those days would face strong headwinds. Although I was fortunate in having a supportive husband and the ability to find babysitters, the climate at Cornell remained unfriendly toward women. In 1972, out of 1453 tenured and tenure track professors, 96 (6%) were women, and, of these, half were in Home Economics; only two were in Arts and Sciences. No women served in high level administrative positions.11 As late as the late ’70s the Chair of the Economics Department was overheard referring to the sole woman serving as an adjunct in the department as “the token woman.”

I managed to cobble together a career comprised mostly of adjunct positions at what seems like every college campus within a 50-mile radius of Ithaca. Contracts were for a semester or a year only with no guarantee of renewal. Ithaca College, where I taught for 12 years—albeit with one-year contracts and no guarantee of renewal—afforded me, newly widowed with three young children, some welcome stability.

In 1972, out of 1453 tenured and tenure track professors, 96 (6%) were women, and, of these, half were in Home Economics; only two were in Arts and Sciences. No women served in high level administrative positions.

I had grown up, perhaps naively, to believe that the “system” was bent toward meritocracy, and so, perhaps, it was—for connected white males. I had two choices: one to believe that I did not have merit; the other to change the system. I chose the latter and struggled with the former. My take was that, if the system wasn’t working as promised, the solution was to change it. I knocked on doors, wrote letters, and knocked on still more doors, trying to convince Cornell that it would be in its interest to establish a parallel non-tenure track research and/or teaching position for people like me—of whom I believed—correctly—there would be an increasing number over time. My efforts went to naught; doors remained shut—until years later when the university established the Senior Lecturer position—non-tenure track, multiple year contracts, with benefits. As usual, I was 20 years ahead of the game. (I was, unfortunately, unaware at the time of parallel efforts by organized groups within Cornell who were pressuring Cornell to expand opportunities for professional women and to eliminate salary differentials between men and women.)

Skills I’d honed in graduate school—reasoning, writing, curiosity, tenacity—transferred nicely into political advocacy in service of the environment and social justice.

Left: 1,731 Cornell graduates gather in Barton Hall for Commencement in June 1960. Credit: Division of Rare and Manuscript Collections, Cornell University Library

The adjunct system, under which I worked, is inherently a lonely place. It can also be demeaning and demoralizing. In the early ’90s, after a last hurrah in Prague, I retired from teaching. My next “career” would be as an advocate—first for an alternative to a proposed regulated medical waste incinerator at the Cornell College of Veterinary Medicine and then for the inclusion of Ithaca public school students with disabilities in regular education classes. Having by then learned that if you want to change the world, it’s likely to take a village, both of these efforts involved organizing and working with a group of committed, passionate people toward a shared goal. Both involved untold hours of unpaid work; both were ultimately successful and personally rewarding. Skills I’d honed in graduate school—reasoning, writing, curiosity, tenacity—transferred nicely into political advocacy in service of the environment and social justice.

Postscript from Mary Frann

It probably shouldn’t have worked—marrying another Cornell graduate student just as I was finishing my PhD, moving to Göttingen, Germany, and still hoping to have a career doing research and writing about Indonesia.

Marrying and “starting a family” meant three children in rapid succession, and “career” meant learning a new language and maneuvering a foreign academic system that was not friendly to women. On the other hand, my husband was supportive of my academic career, and Cornell’s Southeast Asia Program, with its fine international reputation, supportive professors, and many international contacts, helped me to transcend the limited local opportunities. Serendipity did the rest, including the fact that by the 1970s, Germany was beginning to be interested in Southeast Asia, which was my specialty.

I began with a half-time position in the political science department at the university in Göttingen, first as a researcher. Then, over a year later, my husband took up a guest position at the University of Wisconsin. Our first child came along, and although as an infant he took up all my time, suddenly, after five months or so, a gap of a few hours opened. With this new perspective I introduced myself to the political science department, where the Southeast Asian specialist was on leave for a semester, and asked if they would like me to teach the course on that subject. Returning to Germany, I dared to teach a similar course at the University in Göttingen—although the students often had to help me out with the language. Meanwhile, my Cornell professor had a suggestion: Cornell Press wanted to publish a German dissertation on Indonesia’s President Sukarno, would I consider translating it? The book, widely read, made possible an international reputation for the author and opened up further career opportunities for me. Later, I was able to work with him when he took charge of a Southeast Asia program at the University of Passau in southern Germany.

Meanwhile, family crises often meant no time for other responsibilities. A daughter had special needs; my husband developed a terminal illness.

After I was widowed, the Institute for Asian Studies in Hamburg (where, thanks to Cornell’s Southeast Asia Program, I had introduced myself), expressed an interest in working with me. I suggested writing a text that would introduce German readers to contemporary Southeast Asia, and they agreed to support and publish it. This gave me a chance to revisit the region, after some 16 years, and refresh my contacts there. When the book appeared, the institute was able to provide copies to a parliamentary delegation about to leave for—Southeast Asia.

As the children became more independent, I took on teaching positions in Hamburg for a few days a week, and later in Passau. In addition, research grants enabled me to revisit Southeast Asia several times, and I managed extended periods in archives and libraries in several countries. Two U.S. universities invited me to teach in summer programs and, for a three-month residence at Australian National University, I took one of my sons along.

With grant support, and in addition to two more survey-type books, I spent longer periods in the Netherlands, completing two books about the history of two less-known Indonesian islands. Later I also took up temporary professorships in Southeast Asian Studies in Berlin and in Passau. Having reached retirement age, I had finally become, briefly, a Frau Professor Doktor. Well into retirement, I continued translating, editing, and writing.

I continued translating, editing, and writing.

Notes

1 “Ruth Bader Ginsburg: From Brooklyn to the Bench,” Cornell Video, Alumni

Affairs and Development and College of Arts and Sciences, Cornell University, recorded at the New

York Historical Society, September 18, 2014.

2 “Enrollment at Cornell University Ithaca, 1868 to Present,” Home, Institutional Research and Planning, Division of Budget and Planning, Cornell University, accessed March 15, 2024.

3 There are various illuminating and interesting sources for information on Cornell’s early history vis-a-vis women. For a brief background, it might be worth referring to the following sources:

Altschuler, Glenn C., and Isaac Kramnick, Cornell: a History, 1940-2015, Ithaca: Cornell University Press, 2014.

Conable, Charlotte Williams, Women at Cornell: The Myth of Equal Education (Cornell University Press, Ithaca:1977). Conable is especially strong on (and critical of) the role of women at Cornell and the history. She writes, “Once the university made the decision requiring women to live in dormitories while men did not, the opportunity offered to women was no longer the same but different, not equal but unequal. As men were encouraged to become intelligent, competent workers and leaders, most women were prepared for more limited roles as educated wives and mothers. After decades of coeducation, in which women had proven their physical and intellectual ability to achieve an education in a university with men and dominated by men, the end result adhered more closely to Rousseau’s goal of educating women for men, rather than Harriet Mill’s ideal of educating women for themselves and for society” (132-133).

Edmondson, Brad, Postwar Cornell: How the Greatest Generation Transformed a University, 1944-1952, Cayuga Lake Books, Ithaca, 2015, Chapter 5. Although this goes only to 1952, it quotes contributions from women on their experiences as students at Cornell at that time. It is a pictorial history.

Preston, Sergio, “Lives Sacrificed to a Beautiful Building: The Early Years of Sage College, Housing Coeducation and a Reversal of Spatial Autonomy, ACSA Fall Conference, “Play with the Rules,” 2018.

4 Altschuler, Glenn C., and Isaac Kramnick, Cornell: a History, 1940-2015, Ithaca: Cornell University Press, 2014, 148.

5 “History,” Cornell University Big Red Marching Band, Official Website, accessed March 15, 2024.

6 Altschuler, Glenn C., and Isaac Kramnick, Cornell: a History, 1940-2015, Ithaca: Cornell University Press, 2014, 62.

7 Altschuler, Glenn C., and Isaac Kramnick, Cornell: a History, 1940-2015, Ithaca: Cornell University Press, 2014, 60-61, 122-123.

8 In 1959, one third of undergraduate women enrolled at Cornell were in the College of Home Economics, compared with about 10% today in what is the more diversified College of Human Ecology. Source: “Enrollment at Cornell University Ithaca, 1868 to Present,” undergraduate enrollment by gender and college, Home, Institutional Research and Planning, Division of Budget and Planning, Cornell University, accessed March 15, 2024.

9 Altschuler, Glenn C., and Isaac Kramnick, Cornell: a History, 1940-2015, Ithaca: Cornell University Press, 2014, 61.

10 Altschuler, Glenn C., and Isaac Kramnick, Cornell: a History, 1940-2015, Ithaca: Cornell University Press, 2014, 61.

11 Altschuler, Glenn C., and Isaac Kramnick, Cornell: a History, 1940-2015, Ithaca: Cornell University Press, 2014, 144.