Cayuga Lake, the longest and deepest of the Finger Lakes, is one of Ithaca’s greatest attractions and beautiful landmarks. However, you may be surprised to learn that beyond being a scenic attraction, Cayuga Lake plays a substantial role in powering both Cornell’s campus and Ithaca High School. In fact, Cayuga Lake serves as the world’s first-ever Lake Souce Cooling (LSC) facility, a renewable energy source! Today, Cornell University regards its LSC facility as “one of the most significant environmental initiatives ever undertaken by an American University” (Cornell University, 2017).

Up until 2009, coal heated Cornell’s campus, but in 2009 the university shifted away from coal towards a combined heat and power system from natural gas (Denney, 2019). According to Bert Bland, the Associate Vice President for Energy & Sustainability at Cornell University, before the LSC facility, Cornell’s central chilled water district used conventional chillers. However, in 1990 the Montreal Protocol was ratified and prohibited the production of CFC refrigerants (Denney, 2019).

In 1993, Lanny Joyce, Cornell’s Director of Utilities & Energy Management, Facilities and Campus Services, brainstormed the idea to develop a lake source cooling facility with the notion that it would bring substantial environmental benefits to Cornell’s energy portfolio if the program was implemented (Cornell University, 2017). While this facility would have been the first of its kind, there were similar facilities that had existed around the world. In 1986 Halifax, Novia Scotia built a seawater cooling system that used seawater to cool buildings in Halifax.

The Lake Source Cooling Facility was formally proposed the following year in 1994, where Joyce and other Cornell staff envisioned using Cayuga Lake as an inexpensive renewable energy source to power Cornell’s campus (Pinsker, 2002). Cayuga Lake’s LSC is the first-ever project to use a lake’s cool water for renewable energy purposes (Peer & Joyce, 2002).

Planning the LSC facility was a long process, taking six years in the making. In 1998 the New York State Department of Environmental Conservation (DEC) approved the project (Cornell University, 2017). After three years of study and over 16 approvals from various agencies and six years of planning, the construction of the LSC facility took place (Denney, 2019). Construction took eighteen months to complete, but the facility became operational in 2000 and was designed to last anywhere from 75 to 100 years (Cornell, University, 2017).

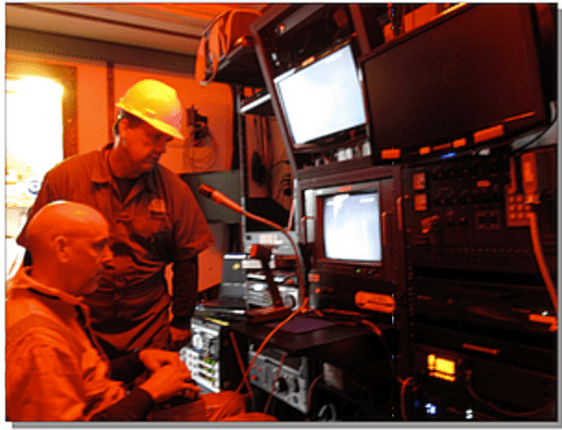

According to Lisa Pinsker, a journalist for the Geotimes, a significant part of the LSC construction was deploying more than 12,000 feet of piping between Cornell’s campus and Cayuga Lake.

By July in the year 2000, the facility resulted in an 86 percent reduction in campus energy usage (Peer & Joyce, 2002). Quickly, the LSC facility was applauded for its revolutionary design and unique renewable energy adaptability. In 2001, Cornell’s Utilities Department won the 2001 New York Governor’s Award for Pollution Prevention (Pinsker, 2002). In 2002, the facility was awarded the New York State Department of Environmental Conservation Governor’s Award for Pollution Prevention. Around the same time, the New York State Department of Environmental Conservation completed a four-year review on the LSC facility and found that the facility could “provide the stated environmental benefits without harm to Cayuga Lake” (Cornell University, 2017).

In 2009, Cornell made even bigger steps and shifted away from coal power towards a combined-heat-and-power system from natural gas (Denney, 2019). According to Bert Bland, there were two important reasons for the transition from coal to natural gas-fired combined heat and power: global warming and the Northeast power outage that was caused by maintenance problems during the summer of 2003.

In an interview, Bland notes that the LSC “[has been] proven to be a financial success, has eliminated the use of refrigerants, has had no negative impact on Cayuga Lake, and has reduced greenhouse gas emissions significantly from avoided electric generation.”

Undoubtedly, Cornell serves as an example of a leader in sustainable energy. In the future, the university hopes to transition towards Earth Source Heat and plans to reach carbon neutrality by the year 2035 (Sustainable Campus, 2021).