James Elkins, writing about the body in Mesoamerican art1 articulates a particularly sensible perspective on material objects, the contingency of analytical categories, and theoretical predilections for reflexive self-awareness:

Perhaps the most common formula [for dealing with the effect of analysts’ biases on their ability to understand the past] could be stated as such: What we see in the past is certainly influenced by our own thinking, but we will be steered toward true accounts by remaining faithful to the historical evidence. This stance, or something like it, has been used as a reason to eschew the philosophy of history and “theory” more generally. If the historical facts do not support whatever biases or theories we have — so this argument runs — then we will automatically tend toward more accurate accounts. There are many reasons to doubt this notion, and they all proceed from one general claim that was first articulated by Hegel: theories, he thought, are what guide our apprehension of “facts,” so that there is no such thing as a fact free of theory. (113)

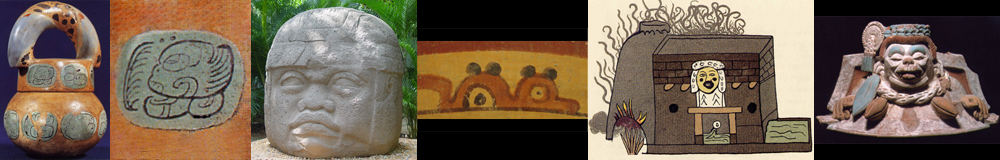

… the most interesting scholarship is the product of informed study of the artifacts together with reflective inquiry on our own cultural situation. Without the archaeological detail, Mesoamerica becomes speculation; but without cultural self-awareness, it becomes the unnoticed projection of our own ideas. In this form, the problem is applicable to any historical research that finds itself engaging with alien material and at the same time spurning historiographic inquiry [by which he means, as he later clarifies, an attempt to understand the Western etymologies of our critical terms/analytical categories]. This is a condition not only of historical knowledge but of knowledge in general. It is more corrosive than this description suggests, since “artifacts” and “archaeological detail” are also names for unnoticed projection, so that ultimately there is no contrast between a firm base of facts and the endlessly cycling groundless self-awareness. Any object, qua object, can set this groundless specularity in motion, and no object, qua object, can settle the difference between seeing mind and seen object. But I am not concerned with this kind of speculation on speculation, because it quickly makes history impossible; it is the particular balances and decisions of historical writing that are of interest. In order to remain within history, and to continue to speak about history, we need to agree on questions that cannot be asked; and it seems to me that this is one such moment. It can be helpful to draw attention back to the self-awareness of the historian, but only if the material object can remain as such: perhaps inaccessible, always difficult, but potentially engaging. (113)

What is needed is a detailed, inch-by-inch look at the images, paired with an historiographic inquiry that tries to find and understand the Western etymologies of our critical terms. Neither strategy alone is sufficient. A theoretical inquiry into the origins and meaning of concepts such as fragmentation, wholeness, or pain cannot make contact with the works, and a myopic but untheoretical analysis will only rehearse unnoticed Western categories of thought. (124)

- Elkins, J. 1994 The question of the body in Mesoamerican art. Res: Anthropology and Aesthetics 26:113-124. ↩