Game Theory and Climate Change

Primary Source:

Newkirk, Vann R. “Is Climate Change a Prisoner’s Dilemma or a Stag Hunt?”

The Atlantic, The Atlantic Monthly Group, 21 Apr. 2016, www.theatlantic.com/notes/2016/04/climate-change-game-theory-models/479340/.

Supporting Source:

Rehmeyer, Julie. “Game Theory Suggests Current Climate Negotiations Won’t Avert Catastrophe.”

Science News, Society for Science & the Public, 29 Oct. 2012, www.sciencenews.org/article/game-theory-suggests-current-climate-negotiations-won%E2%80%99t-avert-catastrophe.

Every year, climate change continues to become a more critical issue that will eventually effect the entire population. Although there are many initiatives to help protect the environment, the rate at which natural resources are exploited largely outnumbers the rate at which they are replenished. This is because the effects of climate change are not immediate, and companies, organizations, and countries cannot economically afford to lessen their dependence or give up a resource, energy source, or invest in polluting less. In the short term, there is a larger economic payoff by contributing less financially to climate change and neglecting the environment.

In his article, Newkirk lends insight into why countries continue to exploit resources despite the future risks and a “potential environmental collapse.” He examines three hypothetical climate change negotiations, each on a different scale: the first between West Virginia and Kentucky, the second between the United States and China, and the third between the major countries involved in the Paris climate agreement.

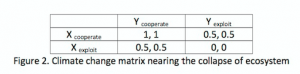

In the first case, West Virginia and Kentucky illustrate the cost and payoffs of either a) cooperating, or b) exploiting a resource when analyzing climate change in the short term. Because these two states are in a competing coal plant market, “acting to protect the environment is costly and has a limited benefit that is far outweighed by the benefit of simply using the environmental resources at maximum efficiency.” Neither state wants to conservatively protect the environment when the dominant strategy is to maximize profit and open up as many coal plants as possible. These payoffs are summarized in Figure 1, a payoff matrix from Newkirk’s article. The future environmental costs are seen as a distant threat in comparison to the competition of the opposing state.

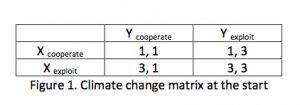

On the other hand, if both players continue to exploit resources, it is imminent that resources will become more scarce. As Rehmeyer claims, in most simulations of a climate change deal, most players continue to neglect the environment if it meant saving in the short term, and “every time, the planet broiled.” As the ecosystem degrades, the payoff matrix begins to look like that in Figure 2 (Newkirk). It becomes increasingly more important to protect the environment and cooperate. This becomes the dominant strategy as exploiting resources (obviously) yields no payoff. As we have discussed in class, this payoff matrix resembles that of a “stag hunt.” Although the dominant strategy is very clear in this scenario, this is the worst case scenario that will only occur when the environment is about to crumble.

Both of these extreme cases are not representative of the climate change situation right now. When countries make decisions about climate change, there are many factors at play, five main considerations being: environmental resource value, future costs of climate change, how likely a policy will affect future costs, the current cost of a policy, and willingness to spend.

As we have discussed in class, although payoff matrices in game theory are helpful in determining how one player will respond to the actions of another, game theory also makes many assumptions in order to simplify and analyze the situation. For instance, all players must be fully aware of their options and the payoff of their options. Before even beginning to analyze a situation, Newkirk himself notes “In each scenario there are a collection of actions that each actor can take. We’ll need to simplify a lot of these actions [and limit options to] two strategies: coordination and defection.” In real life, however, most countries do try and find a balance between cooperation and exploitation (defection). Although Newkirk uses an example of China and the United States with a “Prisoner’s dilemma” matrix, the options for China and the United States are to either cooperate or exploit. These payoff matrices seem accurate enough for extreme cases: either very early when the ecosystem is extremely healthy and lush with resources, or very late when the ecosystem is about to collapse. In today’s case, a more accurate representation of how nations respond would be to create a mixed equilibrium for a more complex payoff matrix. As such, we can’t conclude that climate change in 2017 is either a Prisoner’s dilemma or a Stag Hunt, contrary to the title of the article.