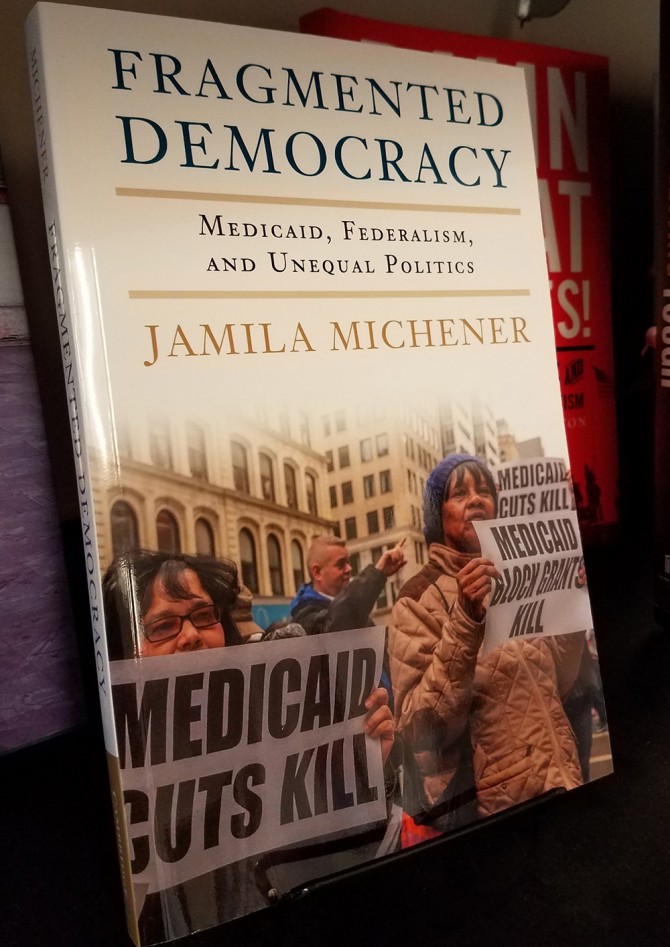

Approximately 74 million people in the United States use Medicaid. But as assistant professor of government Jamila Michener recounts in her new book, “Fragmented Democracy: Medicaid, Federalism and Unequal Politics,” there is no one Medicaid, but rather a patchwork of policies across states with differences even at the neighborhood level.

“The book is about federalism, about how we structure our social policy in the U.S. such that you can get very different things in very different places. And that sends a message to people about how the government operates – not equitably, not even-handedly, not in a way that’s reliable,” Michener said.

“Your value is attached to your residence, whether it’s your state residence, your county residence or your neighborhood residence,” she said. “What this means is that there’s dramatic inequality across place that is literally being created by the structure of our public policy. If you’re an adult on Medicaid and you’re dying, whether or not you can get hospice care is completely dependent on what state you live in. It is not lost on Medicaid beneficiaries what that means about their value in the political system.”

Through analysis of survey and administrative data, and in interviews she conducted across the country, Michener found that variations in state policies directly map differences of political participation among Medicaid beneficiaries. During times when Medicaid is being expanded in a particular place, it can be a boost for political participation there. But in neighborhoods with high levels of disorder and inequality, she found a negative relationship between Medicaid and political participation.

“For many people who receive Medicaid, local clinics and public hospitals are the only place they ever go for health care, so they literally think of those things as the physical manifestations in their neighborhood of Medicaid,” Michener explained. “Medicaid clinics that are falling apart, and have people outside them shooting up, and make you worried if you go there you’re going to get an infection because it’s so dirty, that’s the representation of the government in people’s lives: This is what they get from the government.”

The people she interviewed spent a great deal of time talking about how arbitrary and capricious Medicaid seemed to them, and by connection how arbitrary and capricious the government seemed to them, Michener said. One woman whose visiting grandmother couldn’t get heart medicine covered by Medicaid in that state told her, “If the government really cared about us, they wouldn’t do something like that.”

Despite the problems with the system, people she interviewed expressed tremendous gratitude for Medicaid, Michener said. As one person told her, “It’s better than nothing. If I had nothing, maybe I’d be dead; I wouldn’t have my diabetes medication.”

Michener’s goal for her book was to show the on-the-ground consequences of federalism and how it’s connected to public policy, a set of relationships that is often obscure.

“When we structure policies in a way that promotes inequality, in this case geographic inequality, there are consequences for democratic citizenship,” she said. “We have structured Medicaid in a way in this country that greatly promotes geographic inequality, and it turns out that is also feeding political inequality.”

In her conclusion, Michener advocates for paying attention to the way public policy proliferates political and material inequality, and for a consideration of restructuring public policies to minimize that effect. “We need to think about equality as one of the ways we judge and evaluate policies’ success,” she said. “We’re just not doing that at the moment, and rampant inequality undermines the life of our democracy.”

This article is written by Linda B. Glaser