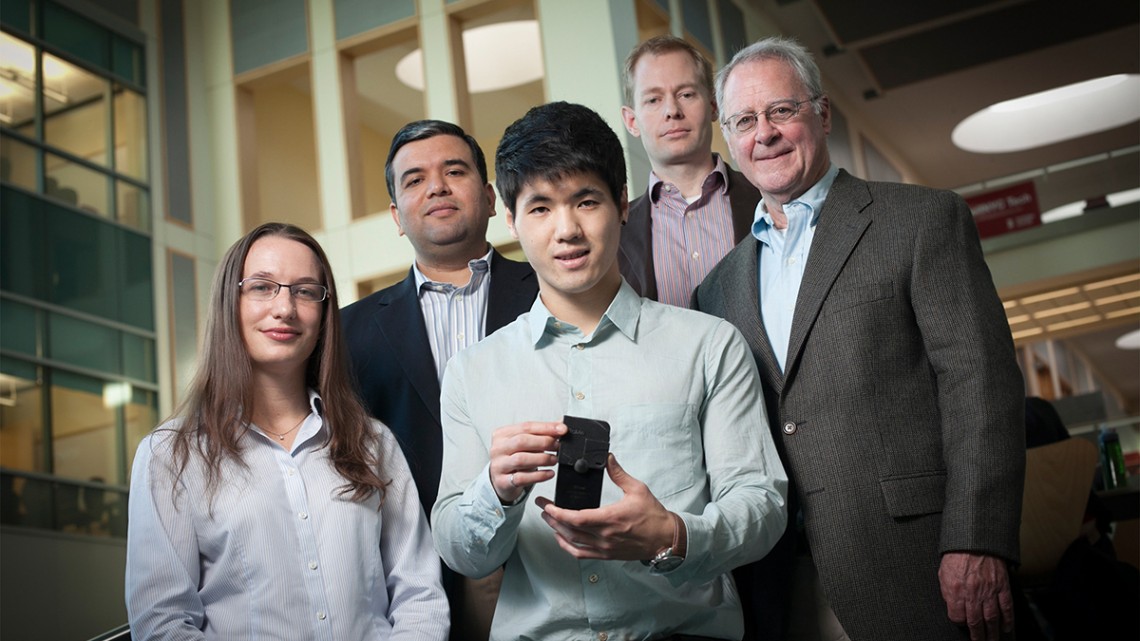

Saurabh Mehta and David Erickson, back row, left and right, respectively, are pictured with NutriPhone collaborators, from left, professor Julia Finkelstein, Seoho Lee and Joe Francis in 2013.

Cornell’s Institute for Nutritional Sciences, Global Health and Technology (INSiGHT) is dedicated to “applying modern technological tools to solve nutritional and global health problems.” Its co-founders are Saurabh Mehta, professor of global health, epidemiology and nutrition in the Division of Nutritional Sciences in the College of Human Ecology, and David Erickson, the Sibley College Professor in Cornell’s Sibley School of Mechanical and Aerospace Engineering.

In the past few years, Erickson’s and Mehta’s projects through INSiGHT have included the development of point-of-care diagnostic devices such as the Cornell NutriPhone and FeverPhone, which can diagnose infections and provide other analyses from a drop of blood in a few minutes. INSiGHT further aims to foster nontraditional partnerships between researchers, implementers, health workers and policymakers to solve complex nutritional and health challenges in areas with minimal resources.

How did you both decide to create INSiGHT?

Erickson: I had an interest in nutrition that grew out of meetings I had with the Department of Defense, and Saurabh had an interest in technology and engineering, so we connected. Barriers are so low at Cornell for these cross-disciplinary and cross-college sorts of things that it made it very easy for us to meet, write joint proposals and get seed funding from places like the Atkinson Center for a Sustainable Future. That grew into the many multimillion-dollar projects we have now, that sit at the intersection between nutrition, infectious disease, global health and technology.

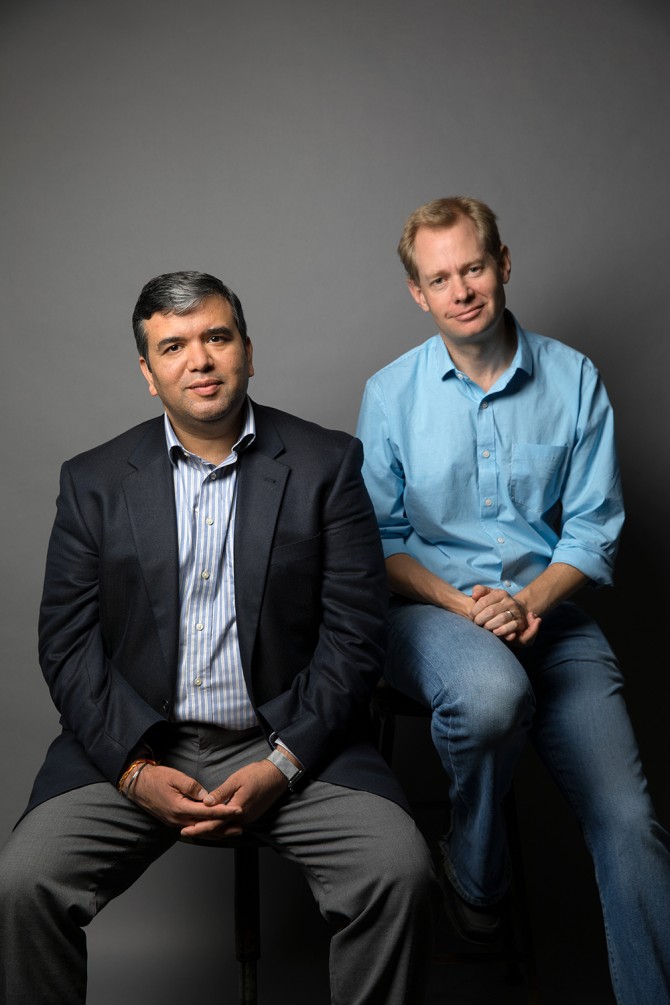

Robert Barker/University Photography. Saurabh Mehta, left, professor of global health, epidemiology and nutrition in the Division of Nutritional Sciences in the College of Human Ecology, and David Erickson, the Sibley College Professor in Cornell’s Sibley School of Mechanical and Aerospace Engineering, are the co-founders of Cornell’s Institute for Nutritional Sciences, Global Health and Technology (INSiGHT).

Mehta: Most of my work is in international or resource-limited settings. A major limitation in most of these settings was we had to send any kind of analyses out to a central lab – samples had to be collected out in the field, we had to maintain a cold chain, we needed to have trained staff. So we wondered, can we make some of these diagnostic tests available, adapt them to be run at point of care?

The idea for INSiGHT was David’s and mine: We wanted to apply modern technology to reduce health disparities. When there is a new technology, usually it’s available to the rich, to people who can afford it – CT scans, MRIs, those kind of things – which are not necessarily available to people in resource-limited settings in the U.S. or international settings.

The driving force was, can we empower the end user – be it the patient or a community health worker, in the U.S. or anywhere else – to make decisions themselves and in real time.

Erickson: One main idea was to empower the individual to take control of their health care, or modifiable elements of their own health care. And the interface for doing that was through the mobile phone. The second idea was, can we take the kinds of technologies we’re developing and deploy them in locations, or economies, in which one would not necessarily have access to good diagnostic services or health care services?

How have technological advances in the past decade enabled what you’ve created?

Erickson: The transformation in the last five to 10 years has been the worldwide uptake in mobile devices. It’s one of the few technologies that has broad, worldwide accessibility. It’s very difficult to go somewhere where you’re not going to have access to one.

The way we interact with mobile devices did not exist in the same way five years ago – and it didn’t exist in the way that it did five years ago, five years before that. We really got in on the ground floor being able to understand how to interact with these devices and how we might deliver health care services through them.

Mehta: And it’s not just the computational power, the imaging abilities, the GPS and everything else … in some of these international settings we were initially thinking that we could equip a community health care worker with one as a really inexpensive way of upgrading their lab capacity. And it would still be point of care.

So the idea that has evolved since is that cellphones really can be considered the mobile health care hub for an individual. Because not only can you record all kinds of data and use it for diagnostic purposes and as a lab, you also can use it integrated with downstream apps where you can change people’s behaviors, give them advice.

Do you consider your partnership a “radical collaboration”?

Erickson: I would say so; I think there are very few places where one can imagine being able to have such tight collaborations within very disparate fields and areas, and have those areas mesh and grow together. So it’s not just the idea of radical collaboration itself; it’s the idea of taking those collaborations and turning them into the big initiatives that will lead the future.

As an example, the Division of Nutritional Sciences has been particularly welcoming to me, giving me a joint appointment, and that allows me to bring my engineering into that field and hopefully develop a whole new area going forward. A lot of places, I think, would be very shy about that.

Mehta: I can share my past experience on this: I’ve mostly been in a medical school or a public health school kind of setting, and I can’t imagine this kind of collaboration would have happened there easily.

There’s a lot of departmental support, and institutional support, that needs to happen to facilitate this, because it’s really a two-way street, especially when we’re in different disciplines. We have different metrics for progress, we have different metrics for impact and everything else. So for us to see eye to eye on what the vision is, I think that’s kind of radical in its own way.

And then, of course, we would like to think of the kind of public health impact we can make in communities around the world, how we can truly transform and revolutionize health care. By that definition and perspective, the way we work together definitely is a radical collaboration.

What have you each learned from the other?

Mehta: I definitely have learned a lot from David. I’ve considered him almost like a mentor to me in many areas. I’ve learned how to maximize opportunities for students and how to maximize interdisciplinary training; but also, on the research side, it’s been eye-opening to realize that when we pool our resources together, these are the kinds of things that we might be able to do.

Erickson: In any kind of partnership like this you’re going to learn something from one another. I’ve learned a lot more about how to interact with people on the international and clinical side, and how to build collaborations, how long building those relationships takes, what kinds of personalities are involved, and how to understand people’s motivations – these are things you don’t really see as an engineer.

As a member of the provost’s Infection Biology Task Force, what perspective does this give you on Cornell’s radical collaboration efforts overall?

Mehta: The university is already set up very nicely for radical collaborations, and the provost’s task forces are a step in the right direction on how to further maximize our collective impact. It has been incredible and educational to me just to see the breadth of talent that’s already on campus. It’s truly impressive.

What are the next steps for INSiGHT and your partnership?

Mehta: There is a lot of work on technology that David and I are constantly engaging each other on, based on needs assessments of the communities we work in or where the science is going.

How do we apply technological methods to solve other problems, not just the ones targeted by the NutriPhone and FeverPhone? How do we engage more researchers and give them a platform to do something similar through INSiGHT? We have also engaged commercialization partners, because we recognize that to really get some of the work we are doing to the community, it has to go out of the academic setting.

Erickson: As some of our work matures, it gets put out there – some through Cornell efforts but also in translation to the commercial sector.

This article is written by Joe Wilensky and was originally published in the Cornell Chronicle on