Meeting Youth’s Needs Through Garden-Based Learning Experiences

Youth Involvement in the Garden

Benefits and Barriers to Youth Participation

“Taming” the Overly Enthusiastic Adult

Additional Resources

“When it comes to working with children and youth in garden settings, all across the nation, we often miss the boat: adults typically plan, design and implement garden programs, inviting young people to the table after the garden is finished. While that isn’t ‘bad,’ it surely misses an opportunity. Our research has shown that gardening interest is more strongly correlated with decision-making than garden activity. It’s worth taking the time to engage young people in every step from the beginning.” –Marcia Eames-Sheavly, Senior Lecturer & Senior Extension Associate at Cornell University

Meeting Youth’s Needs Through Garden-Based Learning Experiences

It is thrilling to witness a child raise a marigold from a seed s/he has planted, or watch a teen-aged youth create a sunflower house for a younger sibling. Even as we are always interested in horticulture, we are stretching toward what constitutes an ideal experience for all gardeners – not just the garden content, but also the life skills gained through the experience. The Circle of Courage is a model of positive youth development which can inform exciting program goals to meet the needs of all participants. It is a model grounded in the principles of belonging, mastery, independence and generosity, and which integrates the cultural wisdom of native peoples and findings of contemporary youth development research.

Mastery: Learning by doing “I can.”

It isn’t difficult to create a long list of all the ways in which someone can gain skills by interacting with the plant world. Hands-on activities, experiential learning, group investigation, and discovery are the backbone of a gardening experience. We encourage educators to focus on the long-term goals of learning and to provide prompt feedback.

A number of years ago, a panel of 4-H youth responded to questions posed by attendees. When asked what frustrates them about the adults in their lives, one teen responded, “You’re all so terrified to see us fail. We can handle it! Let us work it out!” This beautifully exemplifies the desire for mastery. And although it can be one of the hardest lessons in life, in gardening as with everything else, plants die, our goals sometimes aren’t realized, and the beautiful gardens of our dreams occasionally sport weeds. We aim to model and teach that failure and frustration are learning experiences, too.

Belonging: Cultivate relationships “I belong.”

In this busy culture of over-scheduled activity, it’s easy to forget that more than ever, hanging out with each other has tremendous value. It can be ironic that educators may need to schedule ‘down time’ for program participants to get to know one another; doing so is every bit as important as the learning about tomato cultivars or how to compost. Rainy days and other occasions can be a wonderful chance for indoor activities aimed at cultivating connection. For example, older adults often have tremendous knowledge about gardening; talking with them can be a way to promote relationships outside the usual scope of young people’s affiliations. It’s not difficult to promote ties with family and community, since gardening is our nation’s favorite hobby.

Because of all the activity that revolves around the garden, it isn’t challenging to build in small group time to allow for the development of close relationships. Many of the crops we grow have come from all over the world; exploring where our food comes from and celebrating different ways of sharing and preparing food from the garden, for example, can be an exciting way to show respect for the value of diverse cultures. Perhaps most importantly, although plants need to be watered, and the weeds are ever present, a vital aspect of any program is remembering can be to have fun and enjoy one other. Without that, few participants may wish to return.

Generosity: Gestures of thoughtfulness & shared responsibility “I can make a difference.”

When we say the word generosity, frequently what comes to mind is the giving away of “things.” No question, there is often a lot of produce or flowers to be shared when you’re in the thick of a terrific gardening experience, and many people in our communities can benefit from shared food and beauty. But generosity can include much more. A skilled garden-based learning educator reinforces gestures of thoughtfulness, and asks participants to take responsibility for others. Critical reflection, as a part of a service-learning experience, can be an important pursuit that leads to compassion, a broader scope, and life-long interest in the community.

Power: Authentic youth engagement & decision-making “I matter.”

An area that can be over-looked in the rush toward efficiency and getting things done is fostering power, ownership and independence. For example, in the children’s garden arena, often the people who are the most enthusiastic about gardens and gardening are adults. Nation-wide, these adults are calling the shots, designing gardens for children, developing educational programs for children, instead of thinking in terms of partnership. While this isn’t ‘bad,’ it does reduce learning opportunities and the chance to engage audiences in decision making. A major thrust of our focus is fostering genuine participation in community garden-based projects and exploring ways to better engage participants in decision-making aspects of projects.

When it comes to gardening, there are myriad decisions to make, and before making any, we urge educators to reflect on how to share decision-making to ensure a strong sense of commitment. Include participants of any age in planning, encourage their input, and give them responsibility. There are many obstacles in gardening, from deer and other pests, to weather and site concerns; however, we shouldn’t deprive children in particular of the thrill of overcoming a barrier. Their ideas are often more creative and less burdened with “shoulds” and “the way things are” than ours. Ideally, the power ought to slowly shift to participants through self-governance, with respect to garden planning, design, implementation and maintenance. It might mean revising our notion of committees, meeting structures, timing, and an entire approach to how a project is organized.

All of these four themes – mastery, belonging, power, and generosity – are relatively easy to work into any garden-based learning effort. Remember that the ultimate goal isn’t just raising crops; it’s growing competent, committed, reflective, and caring gardeners. Instead of thinking solely of our subject matter expertise, and the important content to be gained from learning about horticulture, it is equally important to consider program factors such as non-scheduled time, opportunities for friends to join in, chances to make a difference in the community, and avenues through which our young participants can voice an opinion.

Your Program

To include more opportunities for mastery, belonging, generosity, and power into your garden-based learning effort, try using the tool Planning for Positive Youth Development Through Garden-Based Learning. Consider an activity: planting pumpkins, planning a new garden, or hosting a harvest festival. How might you expand it? Use the planning sheet to dig deeper and get the most out of meeting the needs of participants in the process.

top

Youth Involvement in the Garden

- This Coins of Strength Activity (doc), illustrates a strength-based approach to working with children and youth versus a deficit based approach.

- Do you engage children and youth in planning and decision-making in your program? Use the Hart’s Ladder of Participation Activity (pdf) to find out!

- Learn more about effective youth engagement with this exercise, Considering Age Appropriate Activities (pdf).

Recruiting Youth

If you’re having a difficult time recruiting youth for your project, take a step back and ask “where did this idea come from?” Think about where your project currently falls on the doing to, doing for, or doing with spectrum. Projects operating with a doing to or doing for approach, tend to have a harder time recruiting youth because they have to recruit youth! If your project is taking a doing with approach, youth have most likely been involved in generating or supporting the idea early on and — through their experiences — have developed a sense of ownership that keeps them coming back.

Encouraging Youth Participation

Encouraging Youth Participation

Often youth garden projects are set up with the assumption that adults plan and build the garden. Youth involvement starts with “fun” activities once the garden is in place. Young people have such great ideas and energy that it seems a waste not to involve them in every step of the process. Additionally, if your garden project is intended to be used by youth, involving them ensures that you’re developing a garden that not only meets young people’s needs but also one which they will find interesting and exciting.

Including Youth as Partners

The benefits of involving youth as partners far outweigh the barriers. If you think involving youth in planning will take too long, take a look at your timeline and consider whether it can be altered. Consider starting small and asking around among your volunteers and potential volunteers to see who might want to spearhead this aspect of the project.

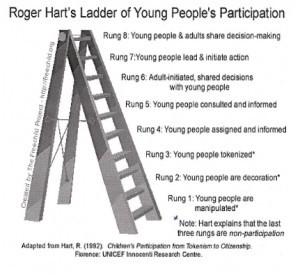

Dr. Roger Hart, co-director of the Children’s Environments Research Group, offers suggestions for involving children in community-based projects. A critical point he makes is to avoid efforts that “decorate” or “tokenize” children’s connection to the project, since this does not represent true participation.

- An example of decoration is when children wear T-shirts promoting a garden program that they neither planned, nor designed, nor implemented.

- An example of tokenism might be a school in which children are involved in a contest to name the garden, but do not have any input in its planning, design, or implementation.

Hart created a “ladder” of participation to help us think about where we really are and where we’d like to be in terms of children’s participation in our programs. This ladder was not created to suggest that we have to be “at the top” rung, but rather, that we ought to be aiming to get out of the lower rungs of non-participation, and think of ways to genuinely engage children and youth. These resources will guide you through: Using Hart’s Ladder Ages 3-6, Using Hart’s Ladder Ages 7-11 and Using Hart’s Ladder Ages 12-18 (pdfs). Visit our Youth Grow curriculum page for an interactive activity that uses Hart’s Ladder as the framework.

Programming for Older Youth

If middle- and high-school aged youth are the target audience, a garden that offers hands-on experiences in the plant sciences, and in the related field of ecology, botany, plant pathology, and entomology, can be very rewarding. High school science teachers often feel that it is difficult to teach plant science because it is viewed by youth as less animated than animal science. In each of the situations below, gardening is combined with one or more disciplines to create a more ambitious experience for the older child.

- Composting is an appealing activity-based focus for older youth that also fosters environmental responsibility.

- Others may want to focus on a different type of stewardship—that of community service—by raising produce for soup kitchens and food pantries. One group of teenagers involved with the Broome County Cooperative Extension returned from a week among the homeless in Washington, D.C. to set up a gardening program to produce food for the hungry.

- Marketing programs are challenging, too, and can offer students a source of income, while giving them skills in horticulture, communication, and business management.

Benefits and Barriers to Youth Participation

Benefits:

- Greater Interest: Increasing youth participation in a gardening program

also broadens the roles young people can play in the project. For example, a talent in art, an interest in math, and a knack for organizing can all lead to a role for a young person who may not be as excited about “plants.” In the same way that adults tend to find their niches of interest within projects, young people may discover that they have an opportunity to do something they enjoy too.

also broadens the roles young people can play in the project. For example, a talent in art, an interest in math, and a knack for organizing can all lead to a role for a young person who may not be as excited about “plants.” In the same way that adults tend to find their niches of interest within projects, young people may discover that they have an opportunity to do something they enjoy too.

- Greater Ownership and Responsibility: People take greater responsibility for things in which they are invested

; if you’ve contributed your time, energy, and ideas to the project, you’re less likely to be destructive towards it or to let others be.

- Building Transferable Skills: Planning projects and making collective decisions requires many skills: communicating your ideas and considering others’ ideas; reaching compromises, working together, problem solving; these are all skills that will benefit those involved in the future, regardless of the project or situation.

- Reduce Time and Costs: Some argue that involving young people in the planning and decision-making process can actually reduce time and costs; by going straight the “users” or “stakeholders,” you reduce the risk of missing the mark and having to make changes.

- Confidence and Pride: Supporting youth in making meaningful decisions and respecting those decisions can boost their confidence in being able to enact change in their communities and in their own lives.

Barriers:

- Adults Have All the Knowledge: It’s hard to make good decisions if you don’t have all the information. It’s also hard to feel ownership and responsibility for something if others don’t trust you or feel that you can‘t handle all the information. Assess whether this barrier is just a matter of getting youth the information they need or if the adults are unwilling to share the knowledge they have.

- Power Distances: Young people are often very far away from the people with the power to make something happen

. How many steps does it take to get from student to school district administrator or 4-H member to city council? Is there a way to bridge that gap more effectively?

- Perceived Capabilities: Young people can’t do this; they don’t have the knowledge/ understanding/ interest/ ability to make these decisions.

- It Takes Too Long: It would be great to have young people more involved but we want the garden finished by the end of next month. (Ask yourself: Who sets the deadlines? Why are they set as such? How flexible are they? Are there benefits to taking more time?)

- It’s Not Always Easy: We don’t have the time, expertise, or resources to involve youth in decision-making on this project. What can you do now with the time and resources you have? Can you start small and increase as you go along?

“Taming” the Overly Enthusiastic Adult

When adult leaders launch a new effort aimed at increasing youth participation, they’re surprised to find that their biggest program challenge isn’t engaging young people; it’s often curbing enthusiastic grown-ups who rush in to “help.” Here are some ideas for fostering participation without bruising feelings of would-be adult assistants along the way:

- Organize a meeting with all parents, teachers, and volunteers who intend to be involved with the project. Talk with them about your approach, what you’re doing, what the children and youth will be responsible for, and how adults might support the project in other ways.

- If you’re hosting an event for children and youth, consider hosting an adult-oriented event or activity concurrently. For example, while children and youth are talking and sharing ideas, adults can be in an adjacent room, generating lists of people in the community

who could provide skills, talents, orfunding – or listening to a presenter on a topic of interest.

- Be very explicit about roles whenever adults are going to be present. For example, in a youth program held at Cornell, adult chaperones were sent a letter in advance that notified them of their roles.

- Organize a special evening opportunity for children and youth to teach their parents or guardians about what they’ve learned in the program. For example, at a harvest dinner or special event, children/youth might walk the adults through the garden, teaching or demonstrating one of the tasks they learned. This may give the adults a better appreciation for the capabilities of their children and youth. This event might also be an appropriate time to talk with children and youth about the roles of adults, things that adults may do to enhance the program, and when these might be most welcome.

top

Additional Resources

Act for Youth, Positive Youth Development 101 Manual

In this activity, youth will collect fibrous plant materials and create handmade paper.

In this activity, youth will collect fibrous plant materials and create handmade paper. This activity gives youth the opportunity to practice and learn the various techniques used in the process of Indigo Dyeing. They will learn about both traditional and modern technologies, history, and science of dyes made from plants.

This activity gives youth the opportunity to practice and learn the various techniques used in the process of Indigo Dyeing. They will learn about both traditional and modern technologies, history, and science of dyes made from plants. Interviews are a terrific way of learning more detailed information from a smaller number of participants, and are often used as a supplement to surveys. They can provide richness and meaning, since they are more open-ended in nature. You may want to purposely select participants for interviewing that may represent varied perspectives.

Interviews are a terrific way of learning more detailed information from a smaller number of participants, and are often used as a supplement to surveys. They can provide richness and meaning, since they are more open-ended in nature. You may want to purposely select participants for interviewing that may represent varied perspectives.