Over 100 years since his death, the world still struggles to understand Scriabin.

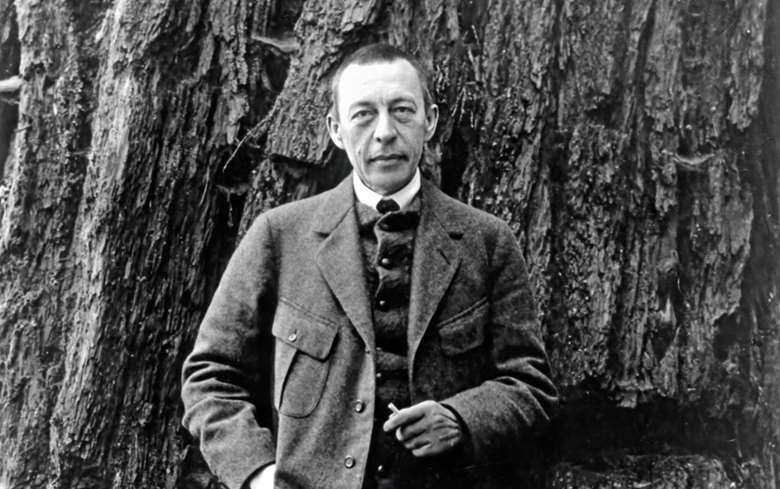

The Russian composer poses at his desk.

Demystifying Scriabin

Mystery and mysticism shroud Alexander Scriabin’s life, acting as both an impenetrable veil and all-encompassing motif. Barely five feet tall, effeminate, and with a mustache to rival that of Nietschze, the Russian composer’s unassuming appearance cloaked an obsession with art that surpassed the boundaries of sanity. His beliefs and music were unparalleled in every aspect. Composition was more than a career, more than a passion, more than the results of artistic mania; it was the means through which he could bring salvation to the planet.

His followers’ cult-like fanaticism impose even more obscurity onto his life. “Cult-like” is perhaps too generous of a term; “cultic” is more fitting. After all, what other composers dubbed themselves “God?” Who else attempted to end the world through their music? Even his death is interpreted as an act of God, who struck the artist down to prevent fulfillment of his musical vision. His followers view him not just as a lover of art, but as its martyr.

In honor of his 150th birthday, Demystifying Scriabin attempts to shed light on the all-too-enigmatic composer’s life, beliefs, and music. Edited by music theorists Kenneth Smith and Vasilis Kallis and published by Boydell Press in 2022, the book is a collection of essays by musicologists and musicians who have dedicated their careers to Scriabin. Smith and Kallis open the introduction by posing the question, “How do you solve a problem like Scriabin?” In between inconsistent spellings of his name, they assert that doing so is a lost cause: he didn’t understand himself and was hell-bent on making sure no one else did either. His writings and beliefs are riddled with inconsistencies and contradictions, and making sense of the senseless is a pointless endeavor. However, investigating his music, philosophy, mysticism, performance, religion, synaesthesia, and cultural legacy can, at the very least, blow away a portion of the haze obscuring his life.

The essays are divided into three sections: Shaping Creativity, The Music as Prism, and Reception and Tradition. Shaping Creativity attempts to demystify by exploring Russia’s impact on Scriabin’s music, a force “represented by the frontiers of disparate musical and cultural trends.” The Music as Prism “offers us a musical way of working through the metaphysical ideas about identity, philosophy, time, and space.” It analyzes his music in relation to his beliefs and life, offering us new perspectives on both specific compositions and his overall body of work. Lastly, Reception and Tradition outlines Scriabin’s influence and “the waves of tradition that passed through him.” Written by a diverse group of Scriabinists, each section aims to both explain the composer and initiate new discussions for this end.

Unfortunately, Demystifying Scriabin is riddled with almost as many issues as the man himself. The book’s divisions appear arbitrary, as the first and third sections both focus on historical influences. Beyond this, the organization of chapters within sections seems random. The first chapter discusses Scriabin’s mystic chord, a recurring device most famously used in Prometheus, and its connection to the Russian Silver Age – yet it’s not until the second chapter, “Scriabin and the Russian Silver Age,” that an adequate description of the era is provided.

While occupying an odd place structurally, the first chapter serves as an intriguing opening. Author Simon Morrison argues that the mystic chord represents the Silver Age through its symbolism. The chord is theorized to represent Satan, and a pentagram can be found through analyzing the relationships between the notes, thereby “becoming the equivalent of a Ouija board.” While this chapter would be better served as an immediate sequel to “Scriabin and the Russian Silver Age,” or perhaps in The Music as Prism, it effectively introduces readers to the mysticism surrounding the composer.

After outlining his writing and compositional influences in the third and fourth chapters, the section concludes with “Studying Scriabin’s Autographs: Reflections of the Creative Process.” The chapter uses the Alexander Scriabin Collected Works to “glimpse a deeper understanding of Scriabin’s creative process.” In the first half, its author, Pavel Shatskiy, thoroughly analyzes the history of the composer’s publishers and the potential errors in original printings and manuscripts. The chapter’s second half uses this information to establish a chronology of when his pieces were written, as opposed to when they were published. This chapter is both out-of-place in the section and unnecessary to the larger goal of the book. There’s no discussion of historical influences, and whether or not Scriabin’s publishers omitted an accent here or there is superfluous to the act of demystifying him. While this is important in other discussions regarding the composer, it brings little to the table in Demystifying Scriabin.

The structure of The Music as Prism is more cohesive. The first chapter, “Scriabin’s Miniaturism,” describes his love for miniaturism, a love influenced by Chopin. This is followed by “The Scriabin Tremor and Its Role in His Oeuvre.” The music theorist Inessa Bazayev argues that analyzing him through the lens of disability studies allows listeners to understand a musical sigh that acts as a motif throughout several of his pieces. She claims that this tremor represents a hand injury Scriabin suffered in his early twenties. While an interesting argument, the essay is purely speculative as she fails to provide evidence that he intentionally based the tremor off of his injury. However, it does bring attention to an under-discussed, widely-used motif in his music.

Editor Kallis reintroduces the mystic chord, this time expanding on the analysis started by Morrison. He argues that the chord is influenced by counterpoint and reflects Scriabin’s reverence for classical traditions of composition. Antonio Grande moves away from pitch analysis in “Temporal Perspectives in Scriabin’s Late Music,” instead opting to approach the body of work from a temporal angle. He defends Scriabin’s surprisingly conventional sonatas, arguing that under a closer investigation, their temporal evolution is avant-garde. Kenneth Smith continues these sonata analyses in “Scriabin’s Multi-Dimensional Accelerative Sonata Forms.” He explains Scriabin’s two-dimensional (and sometimes three-dimensional) sonata form was a trail-blazing innovation, one misunderstood and overlooked by theorists for decades. Ross Edwards wraps up part two in “Setting Mystical Forces in Motion: The Dialectics of Scale-Type Integration in Three Late Works.” He argues that Scriabin’s reliance on the conservative sonata form “set Scriabin’s most radical and ‘mystical’ forces in motion.” While it would have been interesting to read about a wider array of Scriabin’s compositions, the section does a wonderful job of resolving the conservative features of his music with the radical, demystifying him with one analysis at a time.

The third and final section, Reception and Tradition, opens with “Scriabin’s Synaesthesia: The Legend, the Evidence, and Its Implications for Multimedia Counterpoint.” Anna Gawboy does away with the myth of Scriabin’s synaesthesia by examining sources claiming his color system was thoroughly designed and thought out, rather than a psychological condition. The color system was an attempt to access the Theosophical astral plane, “a transcendent realm of spiritual existence that generated life, energy, creativity, and metaphysical knowledge.” He believed it could only be achieved through “clairvoyance, which was characterized by multisensory perception.” Gawboy concludes by stating discussions of Scriabin are unproductive when his music is viewed in isolation from his beliefs – an argument that calls out many of the essays in the book’s second part. However, after reading Kallis and Smith’s introduction, one can’t help but wonder if this goes against the earlier assertion that his beliefs were intentionally designed as meaningless and contradictory.

Marina Frolova-Walker pivots in “Playing Scriabin: Reality and Enchantment” by treating him not as a composer, but as a pianist. The essay begins by compiling accounts of Scriabin’s playing, accounts partially disproven by his existing piano rolls. She then compares these renditions of his playing and argues that none capture what he intended – even those performed by himself.

Kallis and Smith return to provide a general overview of scholarship regarding Scriabin’s music system. Like the concluding chapter of section one, this essay establishes an important timeline, but one that’s generally unnecessary for the purposes of the book. Perhaps it would make sense as a preface to the second section. But as a stand-alone chapter, it doesn’t bolster other information or contribute to the demystification of Scriabin.

The penultimate chapter, Ildar Khannanov’s “Scriabin and the Classical Tradition,” similarly deviates from the book’s theme. He analyzes Scriabin’s compositions in order to determine just how revolutionary he truly was. While Reception and Tradition aims to discuss tradition, Khannanov is the only author to tackle this concept. The chapter feels out of place in relation to its neighbors, all of which discuss his reception. The section seems to have “Tradition” in its title for this chapter alone, a chapter that would belong in either of the previous sections.

James Kreiling ends the book with “Scriabin’s Critical Reception: Genius or Madman?” Kreiling compiles first-hand accounts of Scriabin’s playing, compositions, and personality, contradictory accounts that are unable to answer this question of his sanity. He concludes by speculating that “Scriabin will most likely always be a composer who divides opinions” (319). Only by performing his work with the utmost imagination can his works be understood, and only through approaching him with the greatest openness can his music be loved.

Demystifying Scriabin doesn’t claim to solve or explain the composer – just to demystify and create new dialogue among Scriabinists. Unfortunately, few of its chapters make headway on these fronts. Several, most of which are found within The Music as Prism, are original, interesting, and provide new valuable insights. The remaining majority only contains rehashed information. The world doesn’t need another essay about the dubiousness of his synaesthesia, the influences of the era on his music, or a timeline of his music. Structural issues aside, these remaining problems would evaporate had the book been marketed as a general crash course on Scriabin – but this was not the goal put forth by its editors. However, its failure to demystify speaks volumes of Scriabin. If he truly didn’t want to be understood, this book serves as a monument to his success in that mission.