150 years since his birth, Rachmaninoff’s music lives on as a testament of depression’s inability to destroy beauty.

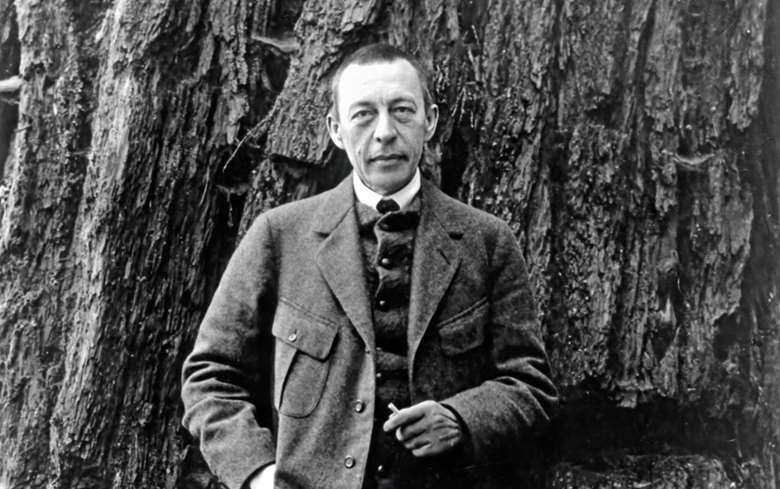

A displaced Rachmaninoff poses in front of a Redwood tree.

Two years had passed. A year of writing, a year of waiting. But the seconds before the opening felt longer still. Drastically underprepared, the musicians nervously awaited their signal to begin. The butterflies in their stomachs were dwarfed by the violent, storm-ridden rainforest within the composer’s. And as the conductor waved his baton, the cacophonic sounds of rainforest flooded the room.

The premiere was a disaster. The audience’s expectations were through the roof, but their disappointment was greater still. It was Sergei Rachmaninoff’s first symphony, after all. But the former child prodigy appeared to have lost his talent at the age of 23. The Russian composer Cesar Cui went so far as to write, “If there were a conservatory in Hell, and if one of its talented students were to compose a program symphony based on the story of the Ten Plagues of Egypt, and if he were to compose a symphony like Mr. Rachmaninoff’s, then he would have fulfilled his task brilliantly and would delight the inhabitants of Hell.”

While the audience escaped the hell at the end of the piece, Rachmaninoff remained in its chasms throughout the following years. The failure led to a deep depression fueled by self-doubt and loathing. But the symphony’s failure was not a result of his inadequacy. The blame lay singularly on the conductor: Alexander Glazunov. Well-regarded for his compositions, his musical talent did not extend to conducting. In this performance in particular, he took one too many creative liberties and one too many shots of vodka beforehand.

150 years since his birth, 80 since his death, depression is still as central to Rachmaninoff’s legacy as it was to his life. His struggles with mental health cast a shadow larger than that of his 6”6’ frame. Historians’ fixation on suffering being a prerequisite to artistic genius is near-pathological when discussing Russian artists, and as a gloomy, Tim Burtonian giant with sunken, elongated facial features, Rachmaninoff’s appearance marks him as a prime target. Yet his looks might have been the source of both his disorder and success. Although he remained undiagnosed throughout his life, Rachmaninoff is theorized to have suffered from acromegaly, a condition marked by malfunction of the pituitary gland. An excessive production of growth hormone resulted in his foot-long hands and distinct facial proportions – but depression resulted as an unfortunate byproduct of the hormonal irregularity. While these struggles served as inspiration for his music, he found himself mentally crippled for years.

His life provided amble kindling for the fire of depression. Born April 1, 1873, Rachmaninoff started off with every conceivable advantage. His family found great success in the military, owned a total of five estates, and provided him with music lessons throughout his childhood. Raised alongside five siblings in estates in western Europe, Rachmaninoff was set for a life of privilege. However, illness and poverty cut his childhood short. His father squandered the family’s money and placed them in near-irreversible debt. After selling all their estates, his father promptly abandoned the family for Moscow, an abandonment both preceded and followed by the deaths of Rachmaninoff’s two sisters.

Rachmaninoff’s grandmother, a devout member of the Russian Orthodox Church, stepped in to rescue him from familial chaos. She tasked herself with reinstating stability through a religious education. This period marked a transformative chapter in the ten-year-old’s life, as his immersion in the rich tapestry of religious music left an indelible imprint on his soul. These influences crept into his musical education at the Moscow Conservatory, where he studied composition and piano throughout the remainder of his childhood.

Under the guidance of Nikolai Zverev, Sergei Taneyev, and Anton Arensky, Rachmaninoff studied alongside Alexander Scriabin in the conservatory. The pair would form a close bond, one later rendered uneasy with maturation of beliefs. Rachmaninoff wrote his first opera, piano concerto, and string quartet during this period and found almost instantaneous fame following his graduation. Inspired by the carillon chimes of the Orthodox Church, he composed his Prelude in C# Minor, a solemn, foreboding, yet melodically gentle piece for the piano. The piece failed to provide him monetary success, but propelled him into the international spotlight.

Rachmaninoff’s popularity did not last. He dedicated the following years to his first symphony, and its failure delivered a colossal blow to both his confidence and career. Attempting to rouse him from depression, his aunt arranged for him to meet Leo Tolstoy in 1900. Rachmaninoff, returning to writing for the first time in years, composed a solo work for piano accompanying a poem by Tolstoy. But upon hearing the piece, the author had only one thing to say: “Is such music needed by anyone?”

These words uttered by the nation’s hero pushed Rachmaninoff over the edge. There was only one course of action: hypnotism. While the efficacy of the treatment is heavily disputed, what cannot be disputed is that Rachmaninoff emerged a changed man in 1901. He completed his Piano Concerto No. 2; he won the coveted Glinka Award; and he soon after found love.

After marrying, Rachmaninoff floated from job to job, working as a teacher, conductor, composer, and pianist. During this period, he wrote The Isle of the Dead, All-Night Vigil, and Symphony No. 2. Although he struggled with bouts of financial instability and the sudden death of Scriabin, he led a peaceful life with his two daughters and wife. But this interlude of happiness ended under the turmoils of political revolt. The 1917 Revolution forced Rachmaninoff to flee the country, and he spent the following years working as a touring pianist. Few pieces emerged during this time. Those that did were marked by his inexorable homesickness and depression. In reflecting on this period, Rachmaninoff said, “I left behind my desire to compose: losing my country, I lost myself also.”

Yet this loss of desire was not absolute. It served as a filter for what needed to be written and what could be written. The few pieces that emerged, such as Rhapsody on a Theme of Paganini, Symphonic Dances, and Piano Concerto No. 4, are among his greatest works. Mirroring the form of his life, almost every prior composition was defined by a simple yet otherworldly melody varnishing a tumultuous monsoon of instruments and notes. The melodic beauty of his music shined through the life-long battle he waged against depression and grief. Abroad and with old age approaching, this monsoon endured, yet was far less pronounced. But his melodies displayed no such retreat. Rachmaninoff pushed his melodic eloquence to unseen lengths, allowing it increased independence from the heavy complexities underlying his previous pieces.

Yet it would be inaccurate to say that Rachmaninoff found peace during this time. His longing for Russia was less extreme than the immobilizing depression of his youth, yet happiness remained an unachievable dream. He wrote of his situation, “I feel like a ghost wandering in a world grown alien.” But his dreams of returning to Russia evaporated under the oppressive Californian sun, where he succumbed to melanoma in 1943.

Despite efforts to relocate his body to Russia, his ghost remains destined to an eternity of displacement. Perhaps we should let him rest. While it was in instability that he created art, his time at the piano is gone. An undying testimony to beauty in spite of anguish endures, one that persists in the hearts of listeners throughout the world.