by Michele Brown

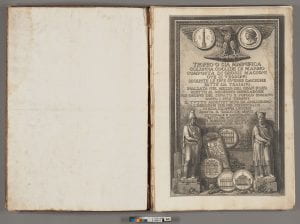

The 18-volume set of bound etchings by the Italian artist, architect and print maker, Giovanni Battista Piranesi (1720-1778) is one of Cornell’s treasures. The Cornell set contains volumes presented in 1774 by Pope Clement XIV (1704-1774) to Henry Frederick, Duke of Cumberland (1745-1790) and brother of the King of England, during his residence in Rome; the volumes that contain works by other artists were added later in the 18th century.

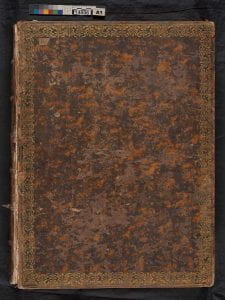

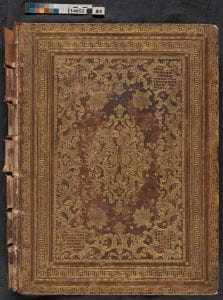

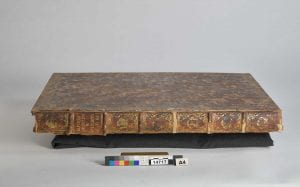

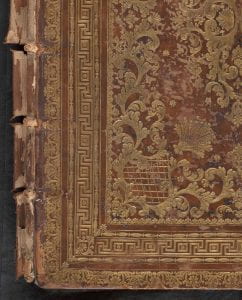

Beautifully bound in full calf (1) in the rococo style, the volumes have matching full gilt spines. Of interest is the difference between the decoration and sewing on Volumes 1 and 2, and the rest of the set. The first 2 volumes are decorated with an elaborate roll around the perimeters of the boards but are otherwise relatively plain; whereas the boards of the remaining volumes are heavily decorated. The first 2 volumes are sewn with recessed sewing and have fake bands on the spines. The remaining volumes are sewn on raised cords

The raised cords are clearly visible under the peeling spine on volume 3. Note the similarities in spine tooling on both volumes.

When Willard Fiske acquired the volumes in 1873, he wrote the following to Ezra Cornell:

“Ithaca, New York, Feb. 19, 1873. Wednesday morning. [To] the Hon. Ezra Cornell. Dear Sir, I am rejoiced to tell you that I last evening received a note from our agent in London, saying that he had secured the Piranesi. All the parts are of the first and best edition — much superior to the second edition published by Piranesi’s son in the early part of this century. Appleton’s Cyclopaedia speaks of these works as “unique in art”. […] The work fills two cases, which arrived in New York [the] day before yesterday [and] we shall probably have them here in ten or twelve days. Respectfully yours, W. Fiske.” (2)

For many years, they were readily accessible to architecture students and were heavily used. Now, due to their fragile condition, access is by appointment only. Restoring them to a usable, working condition is the final project of my career at Cornell.

Their size and condition provide some interesting challenges for restoration and conservation.

Size:

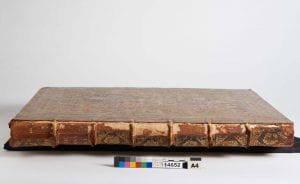

The volumes are atlas folios. Volumes 11-18 measure 21.75” wide by 31” long. Volumes 1-10 are a more manageable 16.5” wide by 21.5” long, but still pose challenges for handling.

Condition:

Most of the bindings are in poor condition. In addition to cracked joints, worn corners, missing endbands, and losses to the covering material, the sewing components (cords and thread) on most of the bindings are extremely brittle.The cords pulled completely away from the spine of volume 16 when we opened the front board for photo documentation. The spine panels of several of the books are in various stages of peeling away from the backs, showing the backs have minimal or no linings. The spine photo of volume 3 (above) shows this clearly.

The sewing was weak or broken in some volumes, resulting in sections becoming detached.

Volumes 15 and 16 have significant water and mold damage. Two etchings had been removed from volume 15 and mounted separately. We decided not to reverse this treatment and reinsert them into the volume.

Previous repair

At some point, the joints and losses of all of the volumes had been treated with a plastic-like substance that matches the description of Liquick Leather, a pva product developed in the 1950s and used to repair leather bindings. (3) Unfortunately, this sort of quick “repair” was common in the 1950s and is seen on books in many libraries . It is impossible to remove without causing damage to the area it has covered. Although, some conservators have experimented with using solvents, it is often removed mechanically. Either way, the original leather surface is usually damaged.

The spines and corners of Volumes 11, 12, 13 and 14 have been skillfully repaired with goatskin, but unfortunately, there is no record of who repaired these volumes or when. Until the 1980’s many of Cornell’s rare books were sent to contract binders for restoration. As was the custom during earlier periods of book restoration, missing tooling was replaced as part of the restoration process. Again, this was expertly done, apparently by someone trained in bookbinding and gold tooling.

Look for upcoming posts about the history of bookbinding and conservation at Cornell.

Proposed Treatment:

These volumes will be rebacked with calfskin; corners will be repaired with Moriki tissue. The missing endbands will be replaced; original spines will be retained, but missing tooling will not be replaced.

My next post will describe treatment of the volumes in more detail.

Thank you to Laurent Ferri, Curator of Pre-1800 Collections, Rare and Manuscript Collections, for his information and suggestions for this post.

Notes:

(1) The books are bound in smooth leather, which looks like calfskin. However, the leather separates and “peels” in a way that’s similar to sheepskin.

(2) In the Ezra Cornell Papers, 1-1-1, box 34, folder 11. Transcribed by Laurent Ferri.

(3) This pdf describing the benefits of Liquick Leather was posted in the discussion section in a blog post by Rita Udina: https://ritaudina.com/en/2015/02/17/bibliopaths-lacquer-binding-book-restoration/