By Elizabeth Burns (H.P.P. ’19)

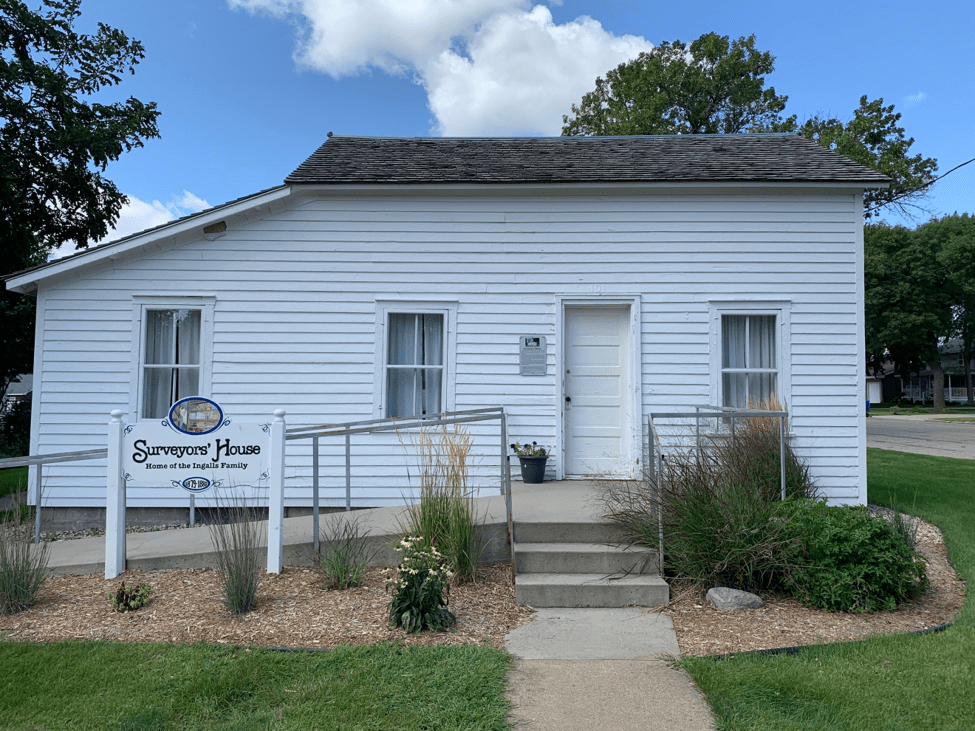

As I stood in front of a small house in the middle of nowhere, South Dakota, staring at the siding that was more than a century old–siding that had weathered tremendous blizzards and oppressive sunshine—I was transported back to my childhood playing in my backyard. To anyone watching, it would look like I was simply pushing a doll around in a wheelbarrow. Still, I was, in fact, traversing the great plains of the United States in my covered wagon finding shelter under the willows lining the riverbank (bushes next to a ditch of rain runoff) or establishing a homestead on which to live (stacking sticks next to the shed to resemble a log cabin). That house I went out of my way to see in South Dakota was the last surviving structure mentioned in the Little House series written by Laura Ingalls Wilder, stories I had so faithfully recreated in my half-acre backyard with a wheelbarrow and a little imagination. That house was not a recreation of history, it was history, and it was my history too. In that instant, I had never appreciated the plight of historic preservation more.

This stop was one of a multitude I made while on an extensive road trip across the United States following my graduation from Cornell and a summer-long internship with the National Park Service. It was a chance for me to fulfill a decade-old dream and after years studying preservation, learning about cities, buildings, and best practices, I wanted to see some things for myself. Going into trip planning, my two goals were as follows: 1. Have fun and 2. Learn something. Preservation wasn’t the focus or the intent, but it’s impossible to avoid.

When I say impossible, I’m not exaggerating. I stopped in St. Louis to see the Gateway Arch, a structure built only after the demolition of hundreds of older buildings along the waterfront, but a structure that itself is being preserved. The national parks where I spent my time hiking and camping continuously deal with the dual necessities of preserving the natural world and the buildings constructed to facilitate the public’s enjoyment of said space. And that doesn’t even account for what I overheard while on the trails. While hiking Montana’s own version of the Highline (an 11-mile trail carved into the side of mountains in Glacier National Park), I had the misfortune of listening to one lady’s tirade regarding the pathetic lack of historic structures in the United States. She disparaged log cabins, said American cities couldn’t hold a candle to European ones, and continued on with other such nonsense. She spoke as if a log structure still standing from the 1800s (or even earlier) isn’t a feat or American cities didn’t present the rest of the world with the skyscraper. I chose to do the magnanimous thing and take a water break.

What I came to understand as I made my way around the country was how ideas spread. I took my fair share of American architectural history courses at Cornell and am familiar with the different styles to the point where I can tell you the general age of the building from its architectural characteristics, but it’s another thing to see Queen Anne homes in Eureka, California; Astoria, Oregon; and Butte, Montana. What you won’t see in abundance out west are Georgian and Federal-style structures as they predate the industrial revolution and the westward expansion of American settlers. It’s easy to understand the theory, but the chance to see this first-hand allowed me to comprehend the intrinsic interconnectedness of the United States and see the movements of history.

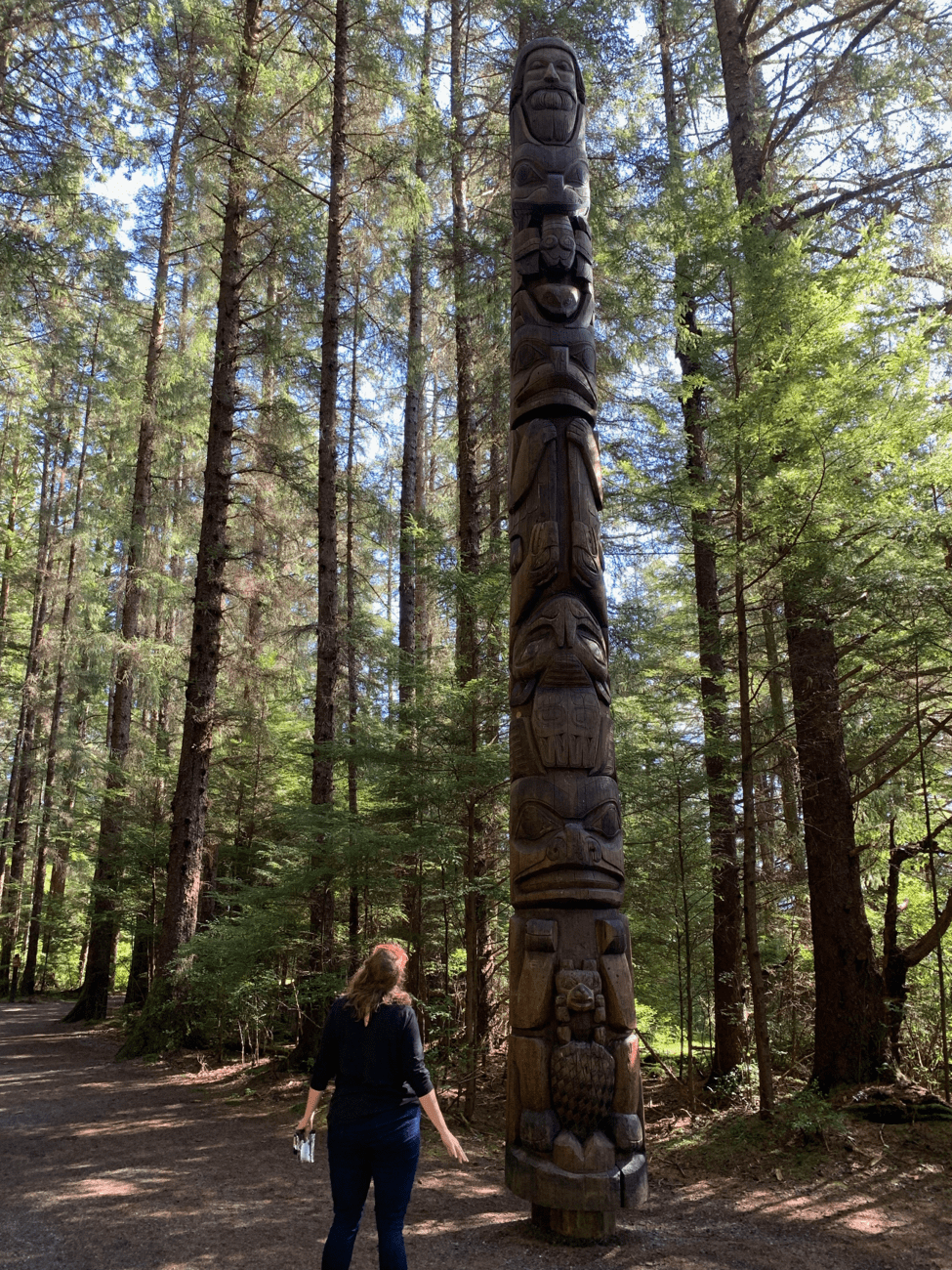

On a jaunt up to Sitka, Alaska, to visit an old college friend, I learned that totem poles traditionally were allowed to decay and return to the earth, but recognition of the importance of the historical objects has led to a push for their preservation.

The rest of my road trip continued much in the same vein. I kept learning and applying what I had learned. A friend and I stood outside of the original Starbucks in Seattle, debating the merits of braving the line for a coffee we could get at another Starbucks two blocks over. I couldn’t help but appreciate how the original Starbucks retained much the same appearance as it did in the 70s thanks to local historic districting.

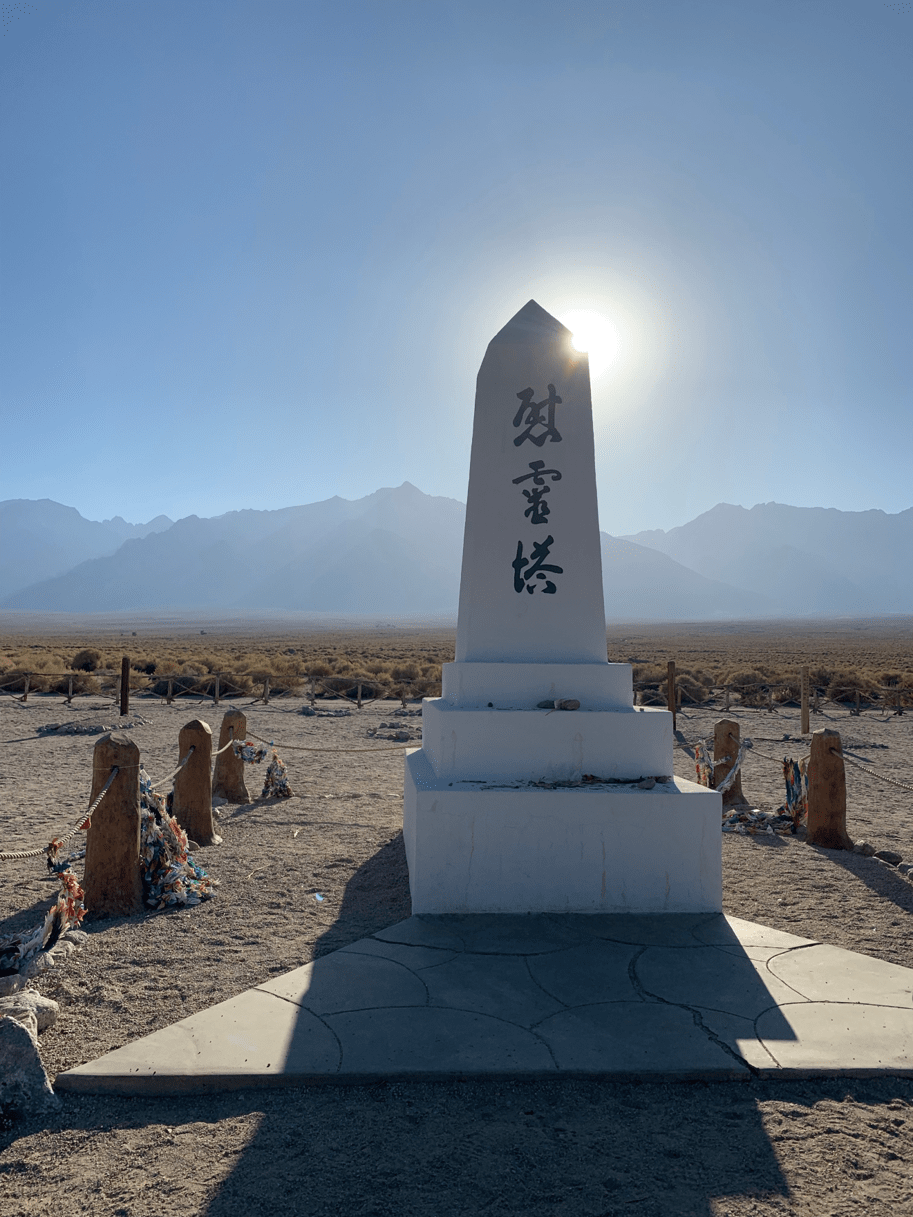

Further south, on the eastern side of the Sierra Nevada Mountains in California, I walked the boundaries of barracks in Manzanar, a War Relocation camp for Japanese-Americans during World War II. Few buildings remain at the site, but each has been painstakingly outlined with painted rocks to convey the sheer size of the camp. It was its own city. A few states east in Colorado, I was visiting fellow Cornell graduates and had the chance to go see Cliff Palace in Mesa Verde. I had only ever seen pictures of it before. Within the week, I found myself wandering through 1,000-year-old building ruins in Chaco Culture National Historical Park in New Mexico. Lobbying to protect these sites from looters led directly to the establishment of the 1906 Antiquities Act, which paved the way for future preservation laws.

Preservation is all-encompassing. If there are buildings, if there is land, if there is culture, preservation will be there in some form or other. My time at Cornell opened my eyes to the interdisciplinary nature of the field. My internships with the National Park Service in comparison were more narrowly tailored, focusing on the federal side of preservation, following strict guidelines, and working on only federally owned sites (granted this account for 400+ sites in the NPS alone). Cornell laid the framework, provided the knowledge and taught me the theories, my internships presented a manifestation of preservation at work, and my road trip showed me the results of this work all across the country. From Yellowstone National Park to the Seattle Space Needle, from the Russian Bishop’s House in Sitka, Alaska to the Palace of the Governors in Santa Fe, each story has been recorded and the buildings preserved. It is history writ large in the most everyday places.