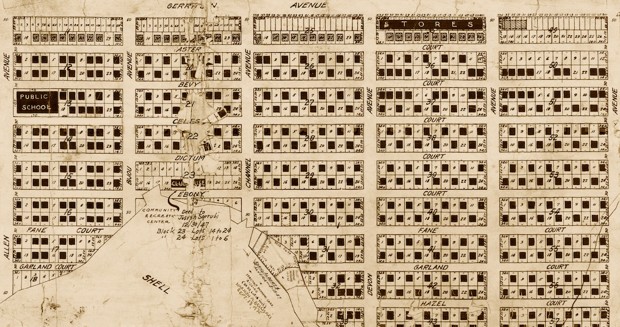

(Brooklyn Public Library)

Associate Professor Thomas Campanella contributed to CityLab, discussing the mass-produced housing in Brooklyn that would serve as a precedent for more commonly known mass-produced housing communities, such as Levittown. Original post can be found on the CityLab website.

Long Before Levittown, Brooklyn Boasted Mass-Produced Housing

The small community of Gerritsen Beach was a pioneering cookie-cutter suburb in the 1920s.

The very next year Greve launched Realty Associates’s most ambitious project—a sprawling community of kitten-cute bungalows—“good and cheap homes for the masses”—at Gerritsen Beach, a salt marsh on Brooklyn’s Shellbank Creek smothered with seven feet of dredged sand. A canal was cut through the center to “provide a Venice-like water front,” according to project engineer Harry Burchell. The homes, Greve proclaimed, would be built “on the same principle that Henry Ford had developed his automobile—that is, on the basis of strictest economy through standardization of plans.”

An on-site cement plant produced concrete foundation blocks. Trucks cycled through dropping off loads of lumber, roofing, windows and trim to each building site—kit houses “all in parts, sashed and ready to be erected over the concrete-cellared foundations.” A corps of 500 laborers, each with a specific set of tasks, moved from station to station on the sandy assembly line. “As soon as the carpenters are through,” Burchell explained, “the plumbing fixtures are installed. Then the painters and paper hangers follow.”

By September 1924, some 600 houses were ready for occupancy—stick-built boxes set in 12-packs on miniature city blocks (about a third the size of those standard elsewhere in New York). Greve’s houses came in five architectural flavors—all with roughly the same floor area and none costing more than $5,750 (a mere $80,500 today). To emphasize their affordability, he initially advertised the homes as “Ford Houses”—until Henry Ford learned of this and threatened to sue for trademark infringement. Unfazed, Greve simply began using his own name and kept on building. All told, some 1,500 “Greve Houses”” were erected at Gerritsen Beach. The company offered financing, too; on a $4,950 house, buyers could close with a mere $350 down and a monthly installment of $65—less than renting.

In 18 months, the instant town boasted a population of 5,000. Gerritsen Beach had its own water plant, with 570-foot-deep wells, a 145,000-gallon storage tank and five miles of water main. Two churches were erected—St. James and Resurrection—along with a community clubhouse (today the Tamaqua Bar and Marina). The city erected several portable classrooms to handle the surging numbers of school children. The buzz attracted other investors. By 1925, two dozen shops and stores had opened on Gerritsen Avenue, and celebrated Brooklyn restaurateur Nicholas Satersen commissioned none other than William Van Alen—architect of the Chrysler Building—to design a 1,500-seat “moving picture theater and dance palace” at the corner of Cyrus Avenue. A victim of the Depression, it was sadly never built.

Isolated on the edge of the metropolis, linked by a single bus line, Gerritsen Beach developed a social fabric as tightly knit as its streets. It had its own Chamber of Commerce, Civic Association, and Citizens Protective Committee, a Lily of the Valley Garden Club—even its own elected “unofficials,” including a mayor and commissioners of parks and public welfare. When the city failed to fix a massive sewage backup in Shellbank Creek, citizens organized a pick-and-shovel army to cut a channel across the Plum Island sandbar to Rockaway Inlet, allowing tidal action to flush the waters.

This insularity also had a darker side. Though I’ve not found evidence of restrictive racial covenants of the sort that barred African Americans from Levitttown, Gerritsen Beach was—then as now—almost exclusively white. The initial population was working-class Irish, Swedish, and German (hence the two churches, one Lutheran and one Catholic). The tight-lipped town with streets dead-ending on backwater canals proved ideal as a base for rum-runners during Prohibition, and stories of basement speakeasies abound. A police shootout with bootleggers on Devon Avenue in 1931 yielded 3,500 bottles of whiskey (1,200 of which the cops promptly spirited off).