This article has been republished with permission by TheNaturalFarmer.org. This article was published as a part of TheNaturalFarmer.org’s spring 2022 issue. You can read the whole issue here.

by Dr. Charles Geisler

I live on land in upstate New York awarded to Revolutionary War veteran, Izaac Doty, for his military service. I also live on traditional homelands of the Gayogo̱hónǫ’ (the Cayuga Nation), a member of the Iroquois Confederacy that predated the Revolution. I purchased my land with income from Cornell University, a Land Grant institution. I tend to think I own this parcel free and clear, yet it is laden with equity issues and moral contingencies that require further truth-telling.

Not infrequently, our land belongs to us because our ancestors claimed territories belonging to its Indigenous inhabitants. In pursuit of profit, power, and dominion, Europeans annexed what they found. In dispossessing others they thought uncivilized, most of our settler forebearers believed that they were doing the right thing. But were they?

In this piece, I’ll comb through the deeply vexing side of land ownership as we practice it. Not many generations ago, Indigenous people partook in a robust spiritual tenure with all quarters of this continent and strong possessory ties of their own making. A lifequake occurred when European culture met theirs. We gradually took their territories and used law, religion, military brawn, and sustained conceit to turn justice into a juggernaut. I will summarize, all too briefly, the settler occupation that unfolded piecemeal across the United States. This will include recent reporting about Cornell University and its sister Land Grant Universities, accused of complicity in a government land grab extending to almost eleven million acres of Indigenous homelands.

Pulverizing Indigenous Lands

The original British colonies sought and gained independence from the motherland in 1783. Thereafter, they mimicked in many ways what had been Royal Charters, land grants, treaties, Eurocentric notions of property and ‘discovery’ as justifications for usurping ‘vacant’ land incidentally occupied by Indigenous people. Despite occasional dissenters like Roger Williams, who founded the colony of Providence in what became Rhode Island and acknowledged full Native entitlement, such land was endlessly coveted by new waves of immigrants. According to Cornell historian Jon Parmenter, in the process of civilizing and pacifying new dominions between 1776 to 1900, the United States purchased, appropriated, or conquered approximately two million square miles of Indigenous land, or two square miles per hour throughout this period.

Land hunger and land speculation were constant artifacts of settler expansion. Speculators included presidents, generals, members of Congress, Supreme Court justices, and Quakers. When Indians were strong in numbers and powerful early in the 19th Century, treaties minimized warfare. Between 1778 and 1871, Congress authored 360 treaties, often on its terms. Treaties were, as stated in the Constitution, “the Supreme Law of the Land.” But as Indians were weakened and displaced by betrayals and forced removals, treaties were disregarded, illegally altered, or, so glaringly in the case of California, never ratified by Congress despite the good-faith compliance by Indians. As the tables turned numerically in favor of the settler society, treaties were renegotiated under terms unfavorable to Native peoples and, even then, breached time and again. Meanwhile, Supreme Court decisions hollowed out the meaning of Indian sovereignty and further diluted Indian negotiating status.

Well before the Homestead Act of 1862 transferred so-called public land from Indian to non-Indian denizens, the Continental Congress and its sequel used endless bounty warrants to recruit settler-soldiers to its military causes with the lure of ‘free land.’ Some military warrants, like that on my parcel, were allocated on traditional Indian lands in the east. Others were designated in the then ‘Northwest Territory,’ Kansas, Louisiana, and beyond. Veterans from the Revolution and the War of 1812 were granted 8,000,000 acres in the Northwest Territory alone, often billed falsely as fertile farmland.

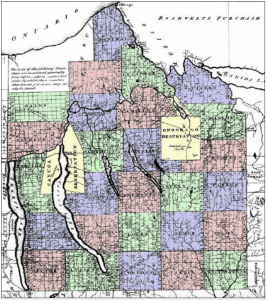

These military land grants, in tandem with the Land Acts of 1785 and 1787, spelled doom for Native inhabitants. The 1785 law established the Federal Land Survey so that land could be sectioned and divided, while the latter established rules for future statehood. Its Article 3 humbly stated: “The utmost good faith shall always be observed towards the Indians; their land and property shall never be taken from them without their consent; and, in their property, rights, and liberty, they shall never be invaded or disturbed, unless in just and lawful wars authorized by Congress; but laws founded in justice and humanity, shall from time to time be made for preventing wrongs being done to them, and for preserving peace and friendship with them.” Indian distrust over land encroachments spawned a decade of warfare led by Little Turtle. Ultimately, General Anthony Wayne met and defeated Little Turtle in the Battle of Fallen Timbers, resulting in the Treaty of Greenville, Indian pacification, treaty-making, and land cessions.

or 1793. Source: commons.wikimedia.org/w/index.php?curid=876328.

The Civil War period, famous for its north-south strife, included tragic east-west bloodshed for Indians. The Homestead Act of 1862 transferred 270 million acres of Native homeland to non-native settlers and speculators, though it hardly ended land speculation. Large acquisitions occurred after its passage. William Chapman alone bought over 1 million acres in California and Nevada; Henry Sage and John McGraw, benefactors of Cornell University, entered 352,000 acres of timberland in the Midwest and the South; Francis Palms and Frederick E. Driggs bought nearly half a million acres of Wisconsin and Michigan timberland; and, as Cornell historian Paul Gates meticulously documented, an era of speculator feeding frenzy overcame Wisconsin.

After the Civil War, Manifest Destiny grew more militant and anti-Indian sentiment mushroomed. Former Union troops strung forts across the west and marched Indians to reservations. By 1871, treaty-making unilaterally ended along with treaty pretexts. Henceforward, no tribe would be recognized as an independent nation, obviating the need for new treaties (existing treaties were left in place, along with their loopholes and abuses). Lands granted to Indians were now subject to Congressional whim and that of lobbyists committed to remaking western lands.

Alas, Indian land loss was far from over. In the

1880s, reservation lands were subjected to aggressive privatization (allotment) under the Dawes Act. Private allotments were carved from reservation holdings in the name of farming and assimilation, “unallotted” lands being purchased by the government and placed in trust. Rip-tide losses of reservation lands followed. Within several decades, the Indian estate plummeted from 130,000,000 to 48,000,000 acres. The proceeds from unallotted land sales, according to plaintiffs in the landmark Cobell v. Babbitt litigation a century later, were grossly

mismanaged and withheld from individual Indian trust funds by the Department of Interior, perhaps in the amount of $150 billion. In 2010, President Obama signed legislation authorizing a $3.4 billion government settlement for individual Indian trust fund holders and a Native Scholarship fund.

This brief account omits countless transgressions that pilfered Indian lands, often by design. The Trail of Tears, associated with the violent dislodging of the Five Civilized Tribes from the southeastern United States to Kansas and Oklahoma Territories, would be reenacted many times for Indian inhabitants and render them, in United Nation’s terminology of today, internally displaced people. But, when Indians became U.S. citizens in 1924, was their land not immune to unlawful government seizure under

protections of the Fifth Amendment of the Constitution?

The answer, according to Indian legal scholars, is yes and no. It is true that until the mid-twentieth century, courts recognized that Indian and Alaska Native property rights were within the Constitution’s guaranteed protection of private property. But in its Tee-Hit-Ton v. United States decision of 1955, the Supreme Court created a new legal rule, concluding that the Constitution does not protect lands held in aboriginal title (title by actual, continuous, and exclusive use and occupancy for long durations). Those Indian and Alaska Native lands recognized in treaties, statutes, or executive orders are constitutionally protected from governmental taking. In other words, Native lands do not enjoy the blanket of protection accorded to your back yard and mine, which, as I hope has become clear, have shape-shifted from Indian hands to ours thanks to the continuing bombardment of hostile government policies.

Land Grabs of Another Kind

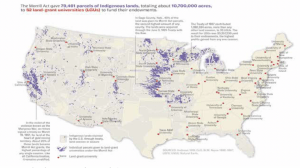

According to the Morrill Act, passed in the same year as the Homestead Act, states holding federal lands could claim and then sell this land to underwrite new Land Grant colleges. New York lacked such lands and, following a federal formula, received certificates (“land scrip”) sold to parties who could acquire ‘uninhabited’ public land further west. The bearer of the scrip would invest the proceeds of land sales and generate revenues for new institutions offering instruction in agriculture, the mechanic arts, and military training. In 1863 the New York legislature, of which Ezra Cornell was now a part, moved to sell scrip totaling 989,920 acres to establish its Land Grant institution. Cornell hastened this action by donating $500,000 to buy scrip for his namesake university along with his Ithaca farm as a potential campus site.

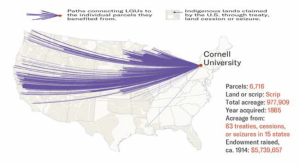

Income from the 1862 Morrill Act gave Cornell University a commanding endowment, one that surpassed those of any sister land grant university. Using his business acumen, Ezra Cornell acquired vast acreages of land deemed “public” by Washington in what would be 15 future states. By 1914 Cornell University enjoyed an estimated $5.7 million in revenues from its land grants or approximately $148 million today. Through Morrill legislation, Indian lands taken by the government were monetized and repurposed for redistribution to state-based post-secondary education. Cornell’s considerable endowment earnings were fulsome, bearing fruit for the Cornell community across generations and for generations yet to come.

Was this a land grab or a gift of free land from the government enabling agricultural education on a continental scale? Is a land grab limited to outright land seizure or does it include wealth wrung from such land and transferred to a third party? As the High Country News authors who thoroughly investigated the matter put it, “The Morrill Act worked by turning land expropriated from tribal nations into seed money for higher education.” High-minded though their mission may have been, the Land Grant recipients of this largesse were complicit in accepting what were spoils of war, of abrogated treaties, and of fraud. Indirectly but undeniably, Indian homeland loss helped to capitalize our 1862 Land Grant institutions.

Grant University. Source: Robert Lee and Tristan Athone, reprinted with permission from High

Country News.

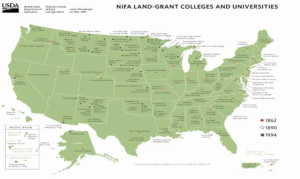

In the latter half of the 19th century, nearly 11 million acres of former Indian homeland would transfer from government hands to those of land agents and speculators anticipated by the Morrill Act. The territories were taken from 240 tribes in 24 eventual states. In 1890, more Land Grant institutions were added, these being colleges for Black Americans denied admission to the Morrill Act schools in Southern states. A century later, in 1994, another 34 Tribal colleges obtained Land Grant status. These 1890 and 1994 colleges received diminished endowments because the great American commons held by its aboriginal inhabitants was long gone.

In founding Cornell, according to Paul Gates, Ezra Cornell relied on western associates for clues to available “public lands.” Much of the Wisconsin land he purchased was former Ojibwa land, ceded under duress through treaties prior to Wisconsin statehood. These treaties were ambiguous, ignored conditions posed by the Ojibwa, offered minimal annuities, and threatened military eviction if breached. The 1837 Treaty alone yielded over a million acres of available land—cessions that went to Cornell and other budding Land Grant universities. Cornell’s land acquisitions in Wisconsin, Michigan, Minnesota and 12 other states eventually translated into nearly one-third of the total Morrill Act Land Grant revenues.

Over time, Cornell teaching, research, and extension have fueled agriculture among the descendants of immigrants and unintentionally fallowed it for Native Americans. No pardons have been extended nor investigations made, until recently, into the magnitude of this imposition. Much the same can be said of Cornell’s failure, until 2020, to acknowledge former Indian tenure of the 17,000 acres it owns within New York State. Most of these in-state lands were not acquired outright with Morrill Act scrip. Yet they could not have been acquired in the absence of the endowment and good fortune bestowed by the Morrill Act.

Obligations and Opportunities

Cornell’s land-grant mission states that a land-grant university should be “expansive, endlessly adaptable, and always relevant.” In 2020 and again in 2021 a group of one hundred faculty and alumni wrote letters to the Cornell Administration about its Morrill Act land history, urging reconciliation with affected American Indian tribes. Hundreds of Cornell students signed a petition with their own demands, and the university’s American Indian and Indigenous Studies Program (AIISP) embarked on a faculty-led “Cornell University and Indigenous Dispossession Project.” In its initial response, the administration publicly acknowledged that its Ithaca campus is historically part of the Cayuga Nation’s homeland and averred that Cornell’s Morrill Act land grant was “accompanied by a painful history of prior dispossession of Indigenous nations’ lands by the federal government.” In terms of action, senior administrators have been cautious. Proposals for new academic programs pertaining to Indigenous studies have been devolved to individual college

deans for consideration and there are nods towards

better recruitment and retention of Native students.

An additional graduate student research assistantship within AIISP has been created, and there is unfinished talk with AIISP about the necessity of contacting Native communities beyond Cornell for insights into new relations and remedial actions. What might Land Grant universities do in response to the collateral damage experienced by Indigenous peoples who unwillingly forfeited ancestral homelands for Land Grant benefit? Government land grabs in the 19th century were problematic in the extreme and recycling these lands for non-Indian higher education is cold comfort to Indigenous people. Land Grant leaders must choose between dissimulation and dedicated engagement. In my view, an enlightened pivot is possible, and Cornell can, by owning its full history, become a platform for signature change. Beyond land acknowledgements within New York and beyond, what would this look like? Among many conceivable initiatives, I offer three that, subject to vetting by Indian stakeholders, seem well within reach of Cornell’s leadership.

Alumni/ae Engagements: When justifying to the New York Legislature the Land Grant institution he was building, Ezra Cornell intoned the words “to do the greatest good.” Those words have become the motto of Cornell’s 2022 capital campaign and are now before a quarter of a million people. Beyond gift-giving, the motto could as well summon new forms of alumni/ae engagement, agency, and accomplishment.

Cornell alums are not wheel-spinners. Many are skilled at tackling great challenges. They are diverse and include a Cornell Native American Alumni Association (CNAAA) with hundreds of members of its own. Native Alumni/ae are a vault of wisdom, sensitivity, and expertise when it comes to relations with their communities. More generally, alumni/ae are Cornell’s working conscience. The majority of people signing the 2020/2021 letters to the administration were alumni/ae and are the tip of a community iceberg committed to “doing the greatest good” on and off-campus.

Cornell alumni/ae sharing this commitment and wishing to uphold their alma mater’s reputation for academic excellence could be a muscle of change on this front. Recent research by Donna Feir and Maggie Jones on Native enrollment and graduation rates in Land Grant versus other institutions found that Land Grants have benefited Native students less than non-Land Grant institutions on both measures. In their words, “Many notions of justice imply that universities whose endowments were seeded by the Morrill Act lands have a greater obligation to current generations of Indigenous students whose ancestors were effectively deprived of their ability to provide opportunities for their children through the taking of their lands without fair compensation.” Alums can pose needed questions of where Cornell falls on measures of Native enrollment, graduation, financial support, and racial equality.

A new avenue for such change is in view. In 2021, Cornell launched the David M. Einhorn Center for Community Engagement, dedicated to opening “new pathways for Cornellians to embrace the university’s Land Grant mission to improve lives.” This is a significant outreach development. The Center aspires to involve Cornell faculty, staff, students, alumni and community partners in efforts at racial justice. Under the heading of “Our team’s commitment to antiracism,” appear the words “We stand with those demanding the end of white supremacy and those pursuing racial justice — at Cornell, in

Tompkins County and across the country. We believe that community-engaged learning can address ongoing violence against and systematic oppression of Black, Indigenous and People of Color.”

Tribal College Engagements: Cornell students and faculty would benefit from cooperation with Tribal colleges in states where Cornell exchanged scrip for former Indian land. These 1994 Land Grant institutions improve career opportunities for Native youth through research, education, and extension programs, often focusing on food, environment, and natural resource challenges. They are tribally controlled and serve populations in underserved communities. In the spirit of Einhorn Center community engagement, Cornell could reach out and explore memoranda of understanding and exchange with Tribal Colleges in states whose public lands profited Cornell’s endowment.

There are precedents. The first Morrill Land Grant University, the University of Kansas, has an M.O.U. with Haskell Indian College in the fields of science/technology/engineering/mathematics (STEM), and provides STEM training opportunities for Haskell faculty. Michigan State University has National Institute for Food and Agriculture (NIFA) funding to do collaborative extension work with Bay Mills Community College, a Tribal College. In 2020, UW–Madison, in partnership with Lac Courte Oreilles Ojibwe College and the College of Menominee Nation, received NIFA funds to foster Native paths from secondary to postsecondary education and incorporate Indigenous knowledge into STEM curricula. In late 2021 NIFA invested $7 million in an array of 1994 Land-grant colleges to enhance student recruitment and retention and do joint research on climate-smart agriculture and forestry on Tribal lands. “Other projects aim to ensure food and nutrition security and support healthy Tribal populations through improving bison herd productivity, uncovering the ways traditional plants can impact diabetes, or controlling invasive species.”

The convergence of Cornell’s interests and those 1994 Tribal Colleges is obvious and could take many forms. Faculty and student exchanges would be mutually beneficial. Imagine Cornell students returning from a “semester abroad” in Indian Country and enriching their classes, clubs, and fraternities with their discoveries. Imagine the growth in racial understanding across the Cornell community if Einhorn Center engagements opened revolving doors at Tribal colleges. Consider the contribution of Cornell’s 80 Alumni Clubs “doing the greatest good” by teaming up with 1994 College alumni/ae on projects of mutual interest. Cornell encourages continued learning via internet classes among its alumni/ae; the same infrastructure could serve this population at both Land Grant institutions in authoring, among other things, a dedicated land curriculum—how land is colonized, distributed, owned, shared, preserved, and sustainably used.

Law School Engagement: The legal concerns of Native Americans, given their encounter with profound discrimination, land theft, and near genocide, are interminable. Top law schools must hire, teach, and train outstanding legal minds equipped with legal tools to resolve the unfinished business of Indian justice. Cornell’s Law School should not minimize its related responsibility as a Land Grant entity nor underestimate the opportunities at hand. In 1976 the first Native students enrolled in the Law School, and a chapter of the National Native American Law Students Association (NALSA) is well established. Its Native graduates enjoy growing prominence. Among the many is Kansas Congress–woman Sharice Davids (who attended Haskell and the University of Kansas before earning her Cornell law degree).

As well, and in tandem with Yale Law School, Cornell’s Law School offers a multi-year Federal Indian Law Practicum. Participating law students represent Tribes and Tribal members in cases across the country. Their source materials include treaties, congressional statutes, tribal codes, executive orders, regulations, federal case law, court decisions, and the Constitution itself. Encouraging as this is, unjust laws still prevent Indian people from recovering their homelands and related livelihoods; how can the whittling away of Indian lands, still occurring, be stopped?

Cornell Law School must deepen its engagement with Indian law and people. It must help the larger university and its Trustees come to terms with the legalities of Land Grant origins and broadened fiduciary thinking.

And there are salient questions needing attention in a truly engaged legal curriculum. Can public land titles be defective where impropriety, disproportionate force, annexation, and deceit are clearly evident? Are land titles of Land Grant institutions, which would not exist but for the forced removal of prior inhabitants, encumbered by the terms of good-faith treaties and trust obligations? As fragile as international law is, what applications has the United States stood behind (e.g., crimes against humanity, genocide, ethnic cleansing, and apartheid) that warrant fuller consideration with respect to domestic aboriginal populations? Similarly, how might jus bellum (Latin for just war) doctrines be made legally relevant on Native American soil taken militarily to expedite nationhood? Equally important, what about jus post bellum (“justice after war”) and winner responsibility to rebuild when hostilities end? The “windfalls for wipeouts” paradigm from planning law (land value capture to compensate land value lost) comes to mind as we come to terms with relevant Land Grant windfalls and Indigenous wipeouts.

Such engagements by Cornell may or may not conform to what Native people want. Their wishes are paramount. Private landowners such as myself, along with diverse public owners and non-profit groups devoted to land conservation, would do well to revisit their land titles, the entitlements they afford, and the origin stories in the shadows of both. Should vast territories be returned to Native Americans to steward, as the distinguished painter/explorer George Catlin proposed long ago? How might non-Natives become more reliable co-trustees of the land with Native Americans? How can we best inhabit the cultural intertidal zone of those who, on so many historic occasions, showed hospitality even as we encroached on their living spaces? My back yard and perhaps yours need amending with generous applications of what Native Americans call “good mind.”

Resources and Links:

High Country News Article, www.landgrabu.org/

Cornell Land Dispossession Page, blogs.cornell.

edu/cornelluniversityindigenousdispossession/

Paul W. Gates, The Wisconsin Pine Lands of Cornell

University, 1943. Cornell University Press, Ithaca,

NY.