By Professor Kurt Jordan

Much like every institution in the United States, Cornell University would not exist as we know it without Indigenous lands. Cornell’s Ithaca campus is located in the traditional homelands of the Gayogo̱hó꞉nǫ’ (Cayuga Nation), who were dispossessed through negotiations with New York State and the U.S. government in which they had essentially no negotiating power. Many of the actions of New York State violated federal law and have been an ongoing source of legal and social contention.

But there is a further dimension to Indigenous lands and the founding of Cornell, one that extends well beyond the boundaries of New York State and entangles Cornell with the dispossession of a stunning number of other Indigenous groups.

Many know the general contours of the history of how Cornell and other land-grant universities were established under the federal Morrill Act of 1862. Such institutions – one per state – were established

to teach such branches of learning as are related to agriculture and the mechanic arts … in order to promote the liberal and practical education of the industrial classes in the several pursuits and professions in life. (7 U.S.C. § 304)

To fund this endeavor, the U.S. government provided grants of federally-held public lands that could be managed as speculative real estate by the institutions. Each state received 30,000 acres of land for each member of congress the state held following the 1860 census. Those institutions in states that had federal land within their borders received lands there, but many states (like New York) did not have sufficient federal lands and were awarded “scrip” (vouchers) to purchase public land elsewhere.

Cornell’s founder Ezra Cornell has long been recognized as a particularly savvy manipulator of scrip. The most famous instance of this was his acquisition of timber-rich former Indigenous lands in Wisconsin, which actually provided three separate types of revenue: they initially were logged and the timber products sold, then the land itself was sold, and finally, Cornell University has retained (and continues to profit from) mineral rights to some of that land to this day. This process is detailed in Cornell historian Paul Wallace Gates’ 1943 book The Wisconsin Pine Lands of Cornell University.

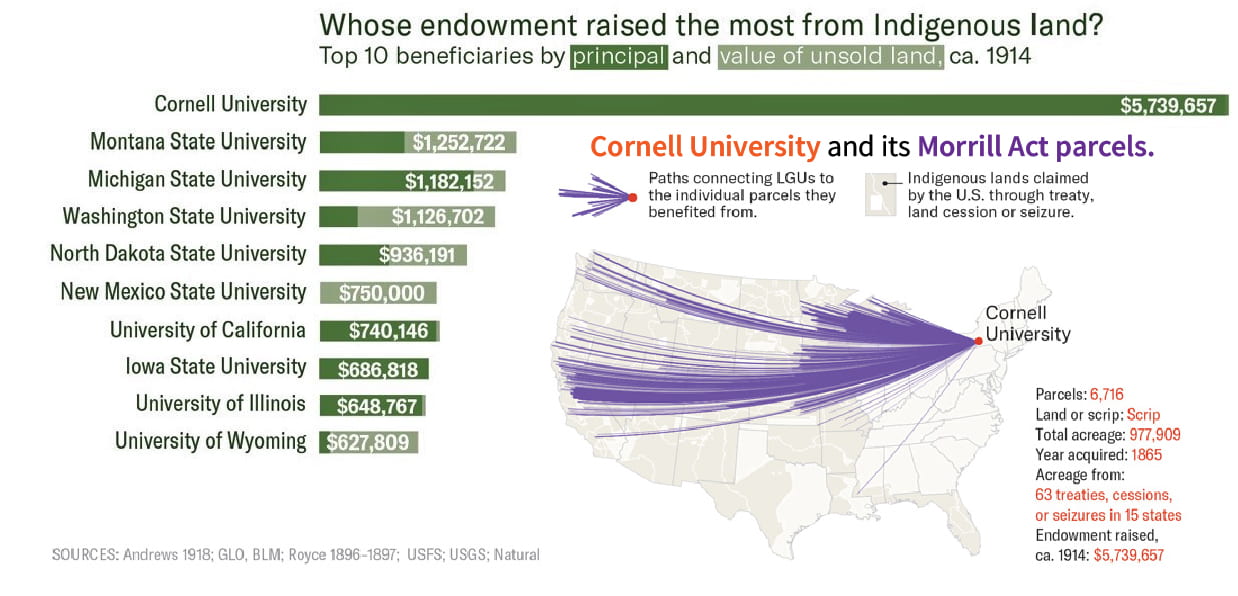

This story, unfortunately, goes much deeper than a celebration of Ezra Cornell’s business skills. A March 30, 2020 article published in High Country News by Robert Lee, lecturer in American History at the University of Cambridge and Tristan Ahtone, editor-in-chief of the Texas Observer, connects the awarding of federal “public” lands through the Morrill Act to the dispossession of Indigenous Nations from their traditional territories. The authors, alongside a team of other researchers, painstakingly reconstructed the details about the lands awarded to the various Land-Grant schools, whose homelands they were, and how much money the universities generated from the process. This landmark study provides a window into the Indigenous side of the Land-Grant process, something that has been obscured and ignored in over 150 years of celebratory narratives that focus on the positive outcomes of the Morrill Act.

The federal government acquired Morrill Act lands through treaties (some ratified, but others unratified by the United States Senate), executive orders, and in some cases without any sort of treaty or agreement whatsoever. In all instances, negotiations were backed by the force of the U.S. military and Indigenous Nations often had little or no bargaining power. Frequently violence, much of it genocidal in intent and impact, had taken place to expel Indigenous peoples shortly before U.S. universities obtained the land.

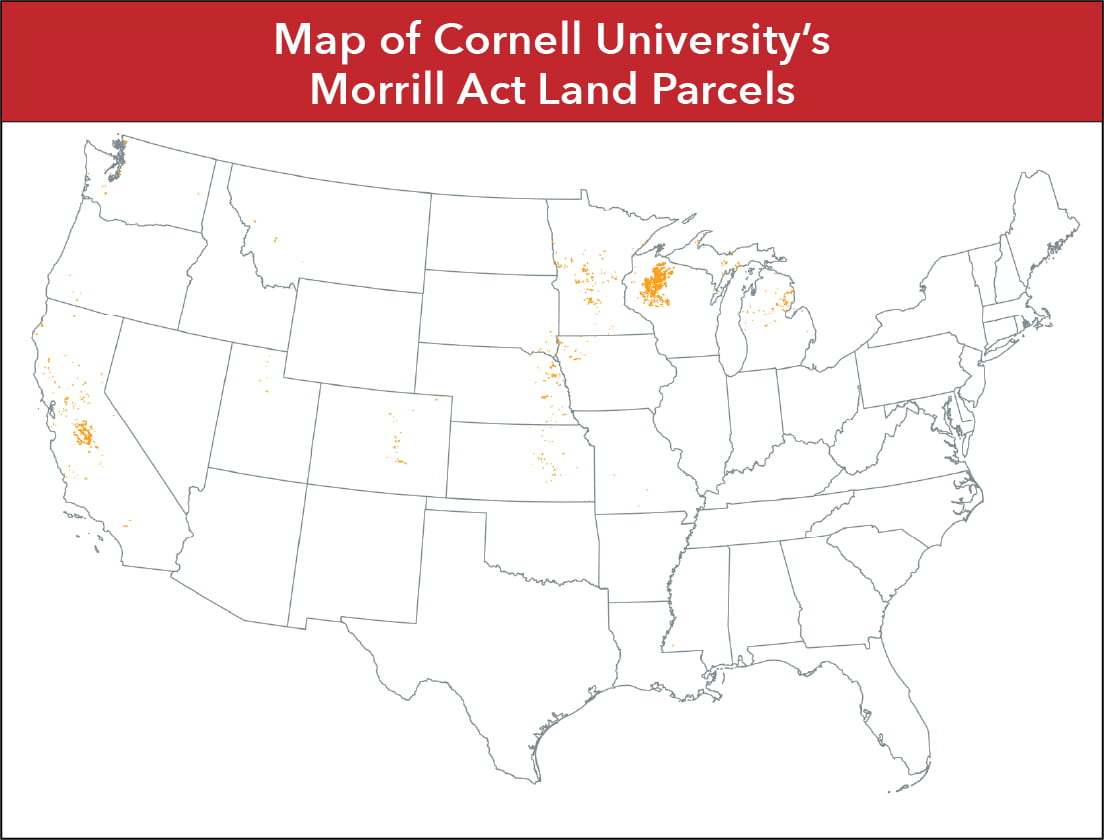

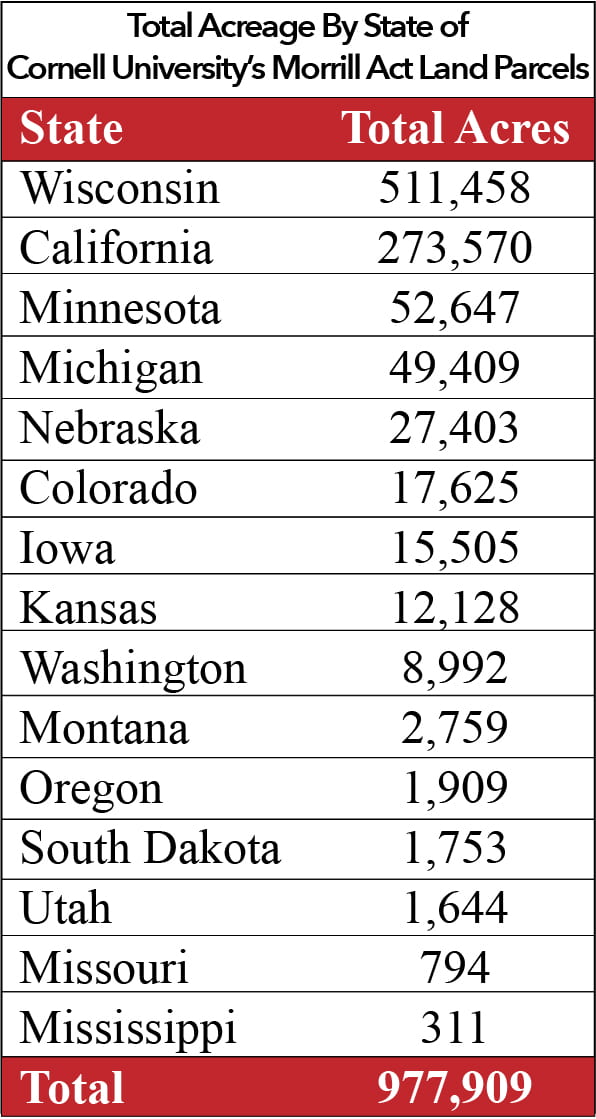

Produced using High Country News‘ land-grab universities project data by Dr. David Strip.

Cornell University occupies a prominent place in this narrative. Lee and Ahtone’s team determined that Cornell received the most land of any U.S. university under the auspices of the Morrill Act, no less than 987,000 acres. This land was located in 6,716 parcels across 15 current states and 202 counties, and by 1914 an estimated $5.7 million had been raised from these lands for the University (this is approximately $148 million in 2020 dollars). As of 1914, Cornell had raised over 4.5 times as much money as the next closest land-grant university (Montana State).

A preliminary Cornell-based examination of this data suggests that as many as 167 Indigenous Nations and communities could have been affected by Cornell University’s actions under the Morrill Act. Land was granted to Cornell within the present-day boundaries of California, Colorado, Iowa, Kansas, Michigan, Minnesota, Mississippi, Missouri, Montana, Nebraska, Oregon, South Dakota, Utah, Washington, and Wisconsin. The largest grants were from California, Michigan, Minnesota, and Wisconsin.

Given Cornell President Martha Pollack’s July 16th call to Cornellians to “think and act holistically to change structures and systems that inherently privilege some more than others,” faculty, staff, students, and alumni in Cornell’s American Indian and Indigenous Studies Program (AIISP) assert that the institution must understand and address the legacy of its founding as an ethical and moral obligation. This narrative should include the dual understanding that Cornell University was not only funded with Indigenous lands but also acknowledge as a policy that it stands on Indigenous lands. The High Country News article explicitly compared the “land-grab university” legacy to that of universities who were built and funded through enslaved labor, and suggested that a similar reckoning should take place (see, for example, efforts at Brown University and the College of William and Mary). As many academic institutions built upon slave labor have done, Cornell has a moral obligation to acknowledge that its origins were based on a continental-scale program of Indigenous dispossession, and educate its faculty, staff, students, and the general public about this history and why it requires action in the present.

To better understand this history and the specific impacts Cornell has had on Indigenous communities, AIISP has formed a faculty committee to examine the issue, consisting of program director Kurt Jordan, Professors Eric Cheyfitz, Jeffrey Palmer, Jon Parmenter, Jolene Rickard, and Troy Richardson, director emerita Jane Mt. Pleasant and program associate director Ula Piasta-Mansfield. Our task is to present information and opinion about the implications of Indigenous dispossession for Cornell and its responsibility to address that history.

We have created a blog where we will post the ongoing results of our research; this statement is the first entry. One aspect of the committee’s activity will be to determine (to the best of our ability) the Indigenous communities affected by Cornell’s land-grab and consult with them about possible remedies. Our blog will present factual information about the Cornell parcels, as well as opinion by faculty, staff, students, alumni, members of the affected communities, and the authors of the generative High Country News article. We will publish both textual and video contributions throughout the fall 2020 semester and beyond.

Stay tuned!