This online blog post features materials protected by the Fair Use guidelines of Section 107 of the US Copyright Act. All rights reserved to the copyright owners.

Blog post by: Rebekah Camp

This striking cloak (CF+TC Accession Number 2005.64.072) epitomizes the trends and luxury of the Belle Époque. From its high, fur-lined collar to its pale, bluish green hue, to its ornate and figural neck clasp, this cloak stands out in a crowd, and its whimsical design choices perfectly align with the carefree opulence of the turn of the twentieth century.

The Cornell Fashion + Textile Collection (CF+TC) dates this garment to around 1900, but we have little documentation of its creation. It was donated in 2006, from the collection of Elizabeth Schmeck Brown, a fashion historian who graduated from Cornell’s College of Home Economics with a Bachelor of Science in 1940, and Master of Arts in 1945. While the cloak was part of Brown’s private collection and her knowledge of textile conservation likely helped preserve the garment, we do not have information on the garment’s original owners; however, we could hypothesize a probable original location of New York or New England, based on the scope of Brown’s collection.

Figure 1. “Ladies Opera Cloak, Pattern no. 5766.” McCall’s Magazine: Queen of Fashion. December 1899. Internet Archive. https://archive.org/details/sim_rosie_1899-12_27_4/page/144/mode/2up.

I will contextualize this garment by examining other contemporary extant garments and fashion magazines in order to determine for whom (generally speaking), and for what occasions, this garment was made, based on how its design reflects the trends of the turn of the twentieth century.

This full-length ‘opera cloak’ or ‘evening cloak’ has applied decorative designs which concur with the opulent fashions of the time. As the name suggests, ‘opera cloaks’ were worn to fancy evening events. Opera cloaks as garments were markers of high status, as these events were generally only within the financial means of the upper-middle and upper classes.

The turquoise green wool of the cloak is another status symbol. “Color and length became subtle indicators of wealth” in contemporary clothing; a light color “would have soiled easily, so presumably the woman who wore [light colors] must have owned a carriage” and could afford to have her clothes washed regularly (Thieme 75). Although the opera cloak in the CF+TC may have faded from its original hue, it would still have originally been light enough to necessitate frequent laundering or infrequent wear, both of which are signs of ample disposable income.

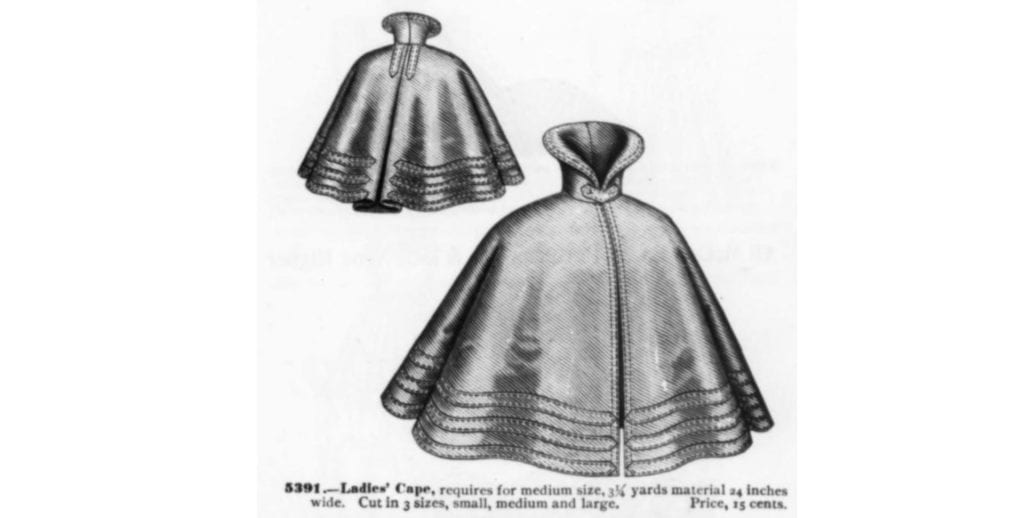

Around 1900, there were many mid-length cloaks (falling to the hip) advertised, in patterns for amateur and professional seamstresses, and as off-the-rack garments, to women of all classes. However, I could find very few references to opera/evening cloaks in McCall’s New York pattern catalogues. There is one pattern, from the December 1899 edition, that advertises a “Ladies Opera Cape” pattern, which “is cut in one piece, dart fitted on the shoulders and trimmed with a shaped circular flounce… edged with fur” (see fig. 1). This construction is different from the CF+TC opera cloak, which has a seam down center back and a longer upper capelet than the ‘collarette’ that adorns the McCall’s pattern (see fig. 2).

In spite of the lack of direct evidence for such a cloak in McCall’s pattern catalogs, the shorter capes advertised along with the trends described in McCall’s fashion advice columns suggest that the CF+TC opera cloak was designed to appeal to the most up-to-date fashions of the period. Like the McCall’s opera cape, the CF+TC cape is trimmed with fur. “Furs are very beautiful this year,” remarks the author of an article in McCall’s December 1900. “Capes…three-quarter coats and long evening cloaks are all made of various furs this season” (“Fashionable Furs” 209). The elaborate lines of topstitching that ornament the hem of cape and capelet, as well as the underside of the upturned collar, are similar to the lines of topstitching ornamenting a far less ornate, single-layer cape that would reach only to the natural waist, advertised in McCall’s in April 1899 (see figs. 3 & 4).

In another article from December 1899, the author writes that this “ubiquitous stitching” was found “on all costumes on which velvet or passemteries are not used.” (“What to Wear and How to Make It” 138). In the same article, the author emphasizes “the immense popularity of velvet this winter,” which is also represented in the CF+TC cloak’s reverse applique diamonds (138). The next month’s issue mentions “trimmings of stitched velvet which decorate our coats,” suggesting that velvet was not only popular, but routinely used as an applied decoration (“The Newest Fads in Dress” 191). Overall, the cloak follows the winter trends of 1899 and 1900 that were advertised to middle-class women.

Figure 3. “5391 – Ladies Cape” McCall’s Magazine: The Queen of Fashion. April 1899, p. 345. Internet Archive, https://archive.org/details/sim_rosie_1899-04_26_8/page/344/mode/2up?view=theater.

Because the cloak was designed for either high society or for those with aspirations thereof, contextualizing it against the designer houses of the time is as important as comparing it to the more accessible contemporary trends, although I do not believe that the cloak’s design is ornate enough for this garment itself to be from a designer house.

Figure 4. Image of the elaborate lines of topstitching ornamenting the underside of the collar on our cloak.

To my surprise, as I perused designer outerwear of the Belle Époque, I found several garments by Jacques Doucet to be the closest applied design analogs. Jacques Doucet is known for “pastel shades decked with laces,” coming out of a long-established family business in “the finest linens, laces, and embroidery” (Coleman 7). In light of this, it’s surprising that unlacey, geometrically decorated outerwear should bear any resemblance to Doucet’s work. However, an evening coat from the House of Doucet, dated to the winter of 1902, has a similar fur trim at the center front opening and a similar tall, fur-lined collar (see fig. 5).

Figure 5. Figure 5 (left): Jacques Doucet. Evening Coat. 1902, The Met, New York. https://www.metmuseum.org/art/collection/search/159006.

Figure 6. Jacques Doucet. Evening Cape. c. 1900-1905, The Met, New York. https://www.metmuseum.org/art/collection/search/155977.

These collars were known as “Medici collars” and were seen on coats, jackets, and capes at the time (“Ladies Golf Cape” 11). Another Doucet evening cape, dating from roughly the same time period, has geometric Grecian swirls in applique velvet on matte silk at the hem (see fig. 6). While the geometric designs are very different in scale and color, the similarities to the CF+TC cloak’s diamond velvet adornments are nonetheless striking (see fig. 7). These similarities are probably not meant as an homage to Doucet, given that the areas of similarity are not in the lace and linens that were Doucet’s specialty. Instead, they are an indicator that this cloak was designed with an eye to high fashion, and incorporated as many elements of the current trends as the taste and budget of the customer allowed.

One of the most distinctive aspects of the cloak’s applied decoration is the agrafe, or decorative metal clip, at the collar (Grimble 415, 519). It portrays a winged figure fighting a dragon (see figs. 8 & 9). The humanoid figure’s wings are apparently angelic, marking it as possibly the Archangel Michael, who fights against the “enormous red dragon” that represents Satan in Revelations (The Bible, New International Version, Rev. 12.3). While the dragon canonically has “seven heads and ten horns,” that would be difficult to construct, and simplification to a one-headed dragon is understandable (Rev. 12.3). Even if this is not the precise reference, the connotation of a dragon-slaying agrafe is one of protection, which is appropriate for a piece of outerwear. Similar “cameo-like heads of Roman emperors and mythological goddesses…and fairies find a place” on buckles and clasps at that time (“Fashion Notes: The Latest Modes a Paris and New York” 196). If mythological illustrations were popular in contemporary metalwork closures, then Biblical allusions were probably equally on-trend, however fanciful they may seem today.

Despite the fact that we have only the briefest of historical backgrounds for this specific garment, we can see how it is in conversation with other garments and recorded trends of the turn of the twentieth century. This reflects the fact that any piece of historical documentation, be it written, drawn, or sewn, can give us insight into the trends and lives of those who lived before us.

Rebekah Camp is in the class of 2025 in the College of Arts and Sciences. Her interests range from historical fashion to art to creative writing. When not attending classes, she can be found roaming the halls of Risley, often wearing a cloak.

Works Cited

Coleman, Elizabeth Ann. The Opulent Era: Fashions of Worth, Doucet, and Pingat. The Brooklyn Museum, 1989.

“Fashionable Furs.” McCall’s Magazine: The Queen of Fashion. December 1900, p. 209. Internet Archive. https://archive.org/details/sim_rosie_1900-12_28_4/page/n23/mode/2up?view=theater.

“Fashion Notes: The Latest Modes a Paris and New York.” McCall’s Magazine: The Queen of Fashion. December 1900, p. 196. Internet Archive. https://archive.org/details/sim_rosie_1900-12_28_4/page/n9/mode/2up?view=theater.

Grimble, Frances, editor. Fashions of the Gilded Age. Vol. 2, Lavolta Press, 2004.

“Ladies Golf Cape.” McCall’s Magazine: The Queen of Fashion. September 1900, p. 11. Internet Archive. https://archive.org/details/sim_rosie_1900-09_28_1/page/10/mode/2up?view=theater.

“Ladies Opera Cape.” McCall’s Magazine: The Queen of Fashion. December 1899, p. 144. Internet Archive. https://archive.org/details/sim_rosie_1899-12_27_4/page/144/mode/2up.

The Bible. New International Version, Zondervan, 2011.

“The Newest Fads in Dress.” McCall’s Magazine: The Queen of Fashion. January 1900, p. 191. Internet Archive. https://archive.org/details/sim_rosie_1900-01_27_5/page/n7/mode/2up.

Thieme, Otto Charles et al. With Grace & Favour: Victorian and Edwardian Fashion in America. Cincinnati Art Museum, 1993.

“What to Wear and How to Make It.” McCall’s Magazine: The Queen of Fashion. December 1899, p. 138. Internet Archive. https://archive.org/details/sim_rosie_1899-12_27_4/page/n7/mode/2up?view=theater.