The stories told by art hold the ability to overcome temporal distances and to drift across continental borders. Throughout history, man has relied heavily on art to unveil fading cultural trajectories, regarding it as a monumental recollection of the past that eventually leads into a foreshadowing of repetition and nuance.

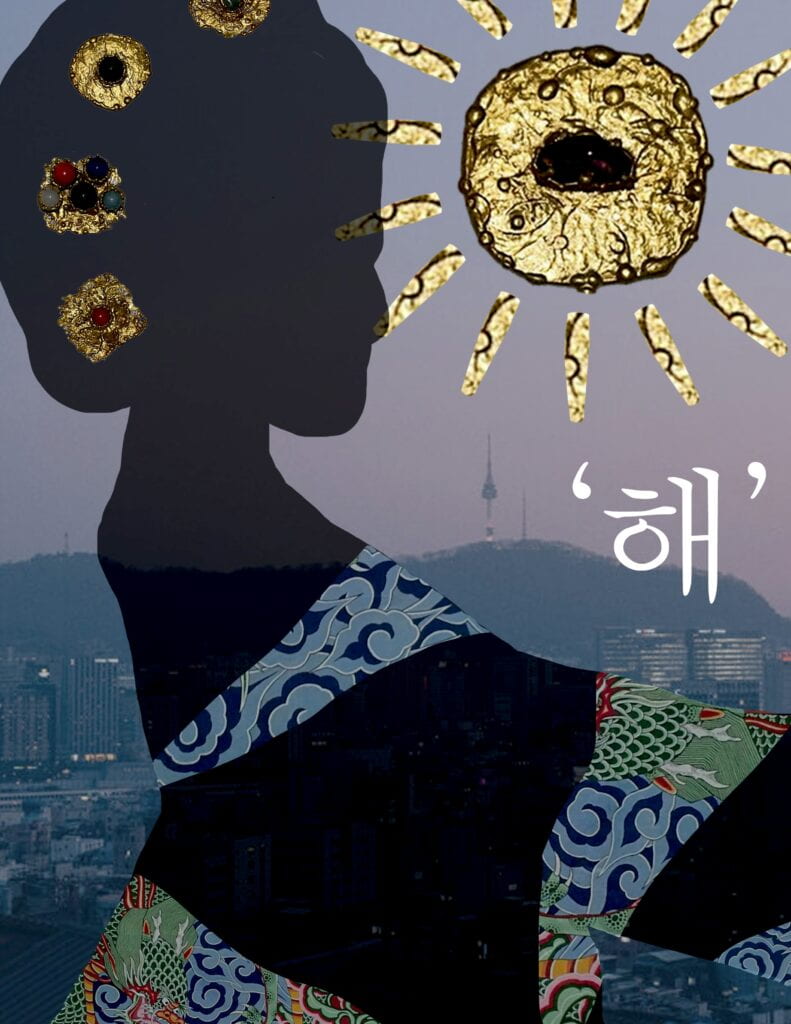

The artifact that grasped my interest at the CF+TC – an assortment of five metal hair accessories embellished with colorful stones at the core, including coral, jade, aquamarine, and amethyst – is a fitting example of such power.

A Bridge Between Past, Present, and Future

The ornaments are the work of Seeun Kim, a South Korean artist who has built her career around the observation of both modern and traditional metal craftsmanship.

“My artworks are typically inspired by the visual culture of the Shilla and Joseon dynasties,” said Kim, upon being asked to describe the historical context behind her work. “Those periods were a time of extensive advancement in both the stylistic and technical features of Korean visual art, which motivated me to use the work of ancient artisans as an inspiration for my own pieces.”

The pictured pieces are a reflection of her approach to the traditional accessories of tteol-jam and dwikkoji, hair ornaments donned by women as an expression of high social status in Korea’s Joseon Dynasty (1392-1910). While close in appearance, the tteol-jam was worn on the front of the head whereas the dwikkoji was placed in the back. Generally referred to as binyeo, the accessories are distinguished by a needle-like tip extending from a decorative piece of molded metal, intended to fix the ornament between tautly-braided locks of hair.

Throughout the dynasties of Korea, accessories functioned as essential tools for socialization and self-representation; they were cherished as emblems of hierarchical standing, amulets to ward off evil, and adornments to achieve harmonization with dress (Lee, 2005). However, as contemporary creations, Kim’s hair ornaments boast a far more robust value beyond their conventional use – they carry with them an essence of her desire to revive and maintain the relevance of Korean visual culture in the future.

A Catalyst to Cultural Diversification

Beyond such historical foundation, Kim’s work is an expressive epitome of the diverse experiences from her educational and artistic career away from her motherland. For this reason, it serves as a medium of cultural fusion and an effort to stimulate global attention toward Korean traditional craft.

While she was born in South Korea, Kim spent the majority of her twenties overseas. During her five years of schooling in Japan, Kim focused on the acquisition of tangible skills as she learned to handle metals to create Japanese traditional accessories at a jewelry-making academy in Shibuya.

Kim then journeyed to England to pursue her master’s degree, where her determination to enter a career in traditional craftsmanship was solidified.

“My time in Japan helped me gain the skills needed to actually create artwork,” said Kim. “But my graduate education in England allowed me to truly analyze the contexts of such works, both culturally and visually.”

Despite the presence of English museums that hold and research Eastern traditional accessories, Kim continued, Korean artworks appear to be less represented in comparison to their Chinese and Japanese counterparts. Because South Korea is a relatively small country with a compact culture, greater strides toward sharing Korean visual culture with the rest of the world are necessary, according to Kim.

“I am East Asian, but one that has seen the lifeways of the West,” said Kim. “As a result, I initially underwent a bit of an identity crisis due to the collision of such polar worlds.”

Along with the passage of time emerged Kim’s vision to channel her appreciation for both the Western and Eastern worlds in her creative intentions. Because she had spent much of her early life away from her mother country yet continued to hold onto its sentiments, she believed that restricting herself to one side of the broad cultural spectrum would be an inadequate representation of her identity; she desired a meaningful balance.

“Through this artwork, I wanted to explore the concept of balance between past and present as well as the East and West,” explained Kim. “I think a major point of motivation for such a project was the pandemic, which encouraged me to reach for more opportunities to unite the Eastern and Western worlds through art and the study of it.”

While the pandemic globally sparked racist attitudes toward those of East Asian heritage, continued Kim, those around her were extremely supportive and protective of her identity as an Asian individual working in the Western world. As a result, she was able to develop the confidence to regard England as a platform for creative projects that envisioned the integration of Korean visual culture and a Western audience.

A Medium of Growth

For Kim, her work is not only a depiction of cultural and temporal expression for a public audience, but a personal space for self-discovery and endless growth as well.

“I’ve worked on over a thousand pieces since 2012 and more than half were failed attempts,” recalled Kim, chuckling. “However, because there were more failures than successes, I believe that I was able to learn so much more in the process.”

If it had not been for such repetition of trial and error, continued Kim, she would not have been able to nurture the deep appreciation and dedication to traditional craftsmanship that ultimately guided her creative germination.

As she reflects on such a trade to which she devoted half of her years to, Kim hopes to continue pursuing her passion for Korean traditional art as well as her vision to become a bridge that extends between distant eras and polar cultures.

“It’s a pathway on which I can look back at my footsteps as an artist,” responded Kim, when asked to define traditional craftsmanship. “Moreover, it’s a striking narrative of our ancestors that connects me with both past and posterity.”

An Interview with the Artist

In February 2024, Kim made a virtual visit to Fashion, Aesthetics & Society (FSAD 2190, taught by Catherine Kueffer Blumenkamp) to speak about her artistic motivations and projects. Below is a transcript of the interview conducted by Erin Yoon.

Q: What would you say is the biggest difference between Asian handicraft and that from Western, European culture?

A: It is very important to interact with diverse people and see, hear, experience, and learn new things. Depending on their upbringing, values, and circumstances, people may have different views, feelings, and thoughts about the world. I am South Korean and studied in Japan and the U.K. I experienced various cultures and societies while studying for my major. I thought the most significant differences between Asian handicrafts and Western European cultures were social ideas and norms.

Historically, Asian countries such as Korea, Japan, and China, and Western countries such as the U.S., the U.K., and Europe made jewelry by carving animal bones or stones. Artifacts from ivory sculptures are still made in Asian countries, including Japan and China. I also trained in ivory carvings to improve my handicraft skills while studying in Japan. However, in Western culture, although ivory has historically been used as a craft material, today, it cannot be used; this is to protect ivory-producing animals.

Another example is mourning jewelry, which originated in England during the Victorian era. Mourning jewelry was made with the hair or teeth of the deceased to mourn the death of a loved one. However, in Korea, neither men nor women were allowed to cut their hair, nails, or teeth casually until the Joseon Dynasty, the last dynasty of Korea. They could not make jewelry with their hair; it was considered a precious part of their body inherited from their parents.

From this point of view, I think that social notions and norms, including the concept of materials, are the most significant differences because the cultural and social backgrounds of the Eastern and Western countries differ so greatly.

Q: How do you think wearing ‘Binyeo’ in a modern context attributes new meaning to its significance, particularly in a multicultural world where many people may not be familiar with its history?

A: Historically, hair ornaments have been used in Korea and other countries as well. Each country’s version has its own beauty, but I think there is a beauty that only Binyeo, Korea’s unique hair ornament, has. With the start of the Korean Wave, today’s young generation wears traditional Korean clothes ‘Hanbok’ and hair ornaments ‘Binyeo’, which can be seen in Korea and foreign countries. Of course, it can feel unfamiliar to foreigners, as if they are wearing a traditional corset and decorating their hair with a luxurious ornament. The public who enjoy or experience our traditional clothes and ornaments in their daily lives, as well as wearing a Binyeo, is thought to have created a new popular culture or a new meaning by showing their attitude toward learning, accepting, and respecting traditions.

Q: What motivated you to study the art of handmade accessories?

A: When I was young, my grandparents always brought me a hairpin or piece of small jewelry as a gift when they returned from a trip abroad for business or travel. It is a happy memory I collected the hairpins and small jewelry pieces I received. Sometimes, I reformed the jewelry and made it my own by connecting plastic beads, and until middle school, I made jewelry as a hobby. I was so happy to give it to my family and friends. It made me feel I had achieved something when I made it into the design I wanted. I wanted to work at what I was most passionate about. So, I decided to be a jewelry designer, and when I was 18, I left for Japan to learn metal craftsmanship.

I believe that the human hand is a gift from human evolution. Even though many advanced technologies exist today, handcrafted products have a sophisticated beauty compared to mass-produced products. Furthermore, there is an inexpressible complexity in the handicraft world that a machine cannot imitate.

Q: Why did you choose to make hairpins as opposed to another type of jewelry?

A: Today, Korea and other countries have more contemporary jewelers than traditional jewelers. When I was a student in Japan, my college offered curriculums for traditional jewelry-making skills. Still, most of my classmates used traditional crafts to make jewelry using modern technology, and I was the only one who made jewelry in the traditional way.

About ten years ago, many people misunderstood Binyeo and thought it was a Chinese or Japanese headdress. Binyeo is Korea’s own traditional headdress. So, I made more Binyeo. Traditional Japanese and Chinese headdresses have different names from each other. It was a meaningful process for me to explain Binyeo’s historical and cultural background by showing people my own Binyeo projects. It also led me to develop an attachment to and passion for Binyeo. In the past and even today, it is rare to see traditional Korean jewelry in foreign museums, compared to traditional jewelry from other Asian countries. Korea is a relatively small country, and the number of traditionally preserved cultural heritage sites is also small compared to other countries. So, I have been completing traditional Korean jewelry projects in the hope that Korea’s traditional cultural heritage will become more widely known to the public and be preserved by our descendants.

Q: What is your favorite project that you worked on, and why was it significant to you?

A: All my projects have been completed with my efforts, attachment, and passion. Nevertheless, I would choose the Braille project if I had to pick my favorite. Today, we use diverse languages to communicate in a modern society. There are many ways of communicating with modern people in the world. Most people speak in their native language or English. However, speaking and listening are not the only ways to communicate with others. I think the use of braille can be another way of communicating. I wanted people to recognise the importance of intangible factors in modern society. So, when I had a solo exhibition last year, I invited visually impaired people. They touched my Braille project, and I could communicate with them. They told me that they had never been invited to any art exhibition for visually impaired people. I decided to continue various social art projects for socially neglected people. It was the most worthwhile moment in my work.

Q: How have your experiences in developing your craft in different areas of the world contributed to your views of pluralism and the intersection of fashion and society overall?

A: I think my experiences developing my craft in different areas of the world have contributed to challenging myself with more diverse projects, breaking the prejudices I held from childhood to my early 20s. For example, I thought only gold, silver, and expensive gemstones could be used for jewelry. It was the first preconception broken when I studied jewelry making in Japan. It was my first learning opportunity to mix various materials and techniques. Twelve years later, I am working on a new jewelry project using eco-friendly materials. Pluralism and the intersection of fashion and society have played a role in my work, broadened my perspective on the world, and developed my values.

Q: What are some of the most significant challenges you face in your craft, and conversely, what do you find most rewarding about working with Binyeo?

A: The most significant challenges I face in crafts are delicate handcrafting skills and perseverance. Machines are also developed by humans, and I think there is no limit to what can be expressed and made by human hands. That is why I think the most fruitful approach is using handcrafting skills that express delicacy. It also takes more than a few years to polish and apply the handcrafting skills, so patience is another big challenge. In addition, related to the Binyeo project, I find it most rewarding when people learn new things they did not know, especially when they become aware of and interested in traditional Korean art culture and Binyeo.

Q: Is there a mindset or method that you think is beneficial when trying to overcome creative challenges?

A: I love traveling. I think my life can be advanced through time by seeing and hearing things I did not know in a new place and breaking down my preconceived notions while broadening my horizons. I get inspiration from it and challenge myself. And I always remember that there is no fixed answer in life.

Q: What inspired you to create the Oxford project and focus on the communication of partially-sighted people? How do material and texture create touch-based meaning in this project?

A: Various social issues and the hard times I experienced inspired me to complete the Oxford project. I remember meaningful phrases in the books when I overcame times of adversity. Shakespeare’s words were compelling in my U.K. life, and I wanted to communicate meaningfully with the public by combining Shakespeare’s words with jewelry. I also wanted to use art to communicate with people neglected by society. Being exposed to different kinds of people and their social problems through world news was the beginning of the project for me. I have also practiced expressing texture using various materials; texture can express not only design but also language. I think it is another opportunity to break down our prejudices. I used relatively inexpensive aluminum and brass, not gold and silver, to break down the prejudice that only expensive materials can be used to make jewelry for people.

Q: The Compromise Project appears to have a very different aesthetic from your other projects. Was there any difference in your line of development and inspiration? How was your experience in working with a different aesthetic?

A: The compromise project has a very different aesthetic than my other projects. I used a lot of wires and artificial materials, and the expression method is very different from my usual craftsmanship. The compromise project was one of my four different social art projects in 2020. It was a motif of the benefits of science and technological development and the abused ambivalence and was also a work made in England during the 2020 pandemic lockdown. It was a new area in my work, and with that opportunity, I completed another social and art project concerning environmental issues. After completing the compromise project, I felt that we must balance strengths and weaknesses appropriately since there are two sides to everything, and these things can develop and change. The compromise project was fascinating as a new, different aesthetic. However, it partially addressed pity as a social issue.

Q: How do you see the future of traditional craftsmanship evolving in our increasingly digital and global society, and what role do you believe artists like yourself play in bridging the gap between tradition and contemporary social matters?

A: Digitalization is an inevitable reality in our daily lives. Perhaps, more and more, there will be fewer traditional craftspeople. Therefore, I think that countries and governments should legally protect traditional craftsmanship and that its promotion should be more diverse in line with the trend of globalization. In Korea, outstanding craftspeople are designated intangible cultural properties, protecting craftsmanship and passing its technology on to people. Compared to them, there are still things I have to learn, but I think artists like me play a role as a bridge between tradition and contemporary social matters so that tradition can be preserved unbroken.

Q: How do you believe Artificial Intelligence will change the artistic paradigm in the future?

A: When I was studying in graduate school, my first assignment’s question was: What tool will be the most useful for humans in the future? My answer was artificial intelligence (AI). AI will pervade many parts of our society, including science and technology, commerce, medicine, and art. For example, I think that basic tools and work facilities for art creation, like the basic living tools we use, will be replaced by AI. This is because as human technology evolves, AI can be applied as much as that technology. For instance, just as we used spoons when we first ate as toddlers, AI is expected to permeate not only art but also our trivial daily lives.

Q: How do you see your work contributing to the preservation or evolution of Korean cultural heritage, particularly in the context of Binyeo?

A: My Binyeo project has been permanently acquired by various museums in Korea, the Oriental Museum in England, and the National Museum of Scotland. In particular, it has been permanently acquired by the Korea National University of Cultural Heritage Museum, the only university affiliated with the Korean Cultural Heritage Administration. I hope my research and work will allow Korean and international students to preserve and study their country’s traditions and culture. They can produce more diverse traditional craftwork than my Binyeo and work differently than I do. Some can become researchers who restore cultural properties, and some can become curators who promote and preserve traditional culture. I think I will be a bridge for them in the future.

Yoon’s writing about Kim’s work is also featured in the Bauhaus Dessau Foundation’s Schools of Departure: Digital Atlas of Design and Art Education beyond the Bauhaus, linked here.