This online blog post features materials protected by the Fair Use guidelines of Section 107 of the US Copyright Act. All rights reserved to the copyright owners.

Blog post by Ashley Kim

I.L.G.W.U. Bronzed Shoe Commemorates the Power of Unity

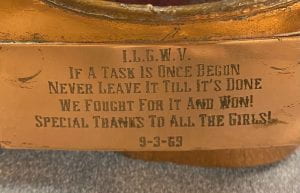

Eye-catching and shining, Cornell University’s Kheel Center for Labor-Management Documentation and Archives houses the “Bronzed shoe” as part of its diverse and impressive I.L.G.W.U. memorabilia collection (Fig. 1). From tip to heel, the bronze loafer measures 12 inches and most likely worn by a woman based on its overall size and shape; the short heel suggests that it was an every-day shoe for work. The entire outside surface of the loafer is coated with a reflective bronze that was likely painted due to its brushstroke qualities and marks on the shoe’s right-side surface (Fig. 2). A greenish-gray tarnish reveals itself most significantly in crevices and the brushstrokes, reflective of its aging process coupled with the bronze discoloration from being handled and exposed to moisture, thus oxidizing over time. Glued onto the left side, a 4×1.5-inch bronzed plate proclaims the engraved words (Fig. 3):

“I.L.G.W.U.

IF A TASK IS ONCE BEGUN

NEVER LEAVE IT TILL IT’S DONE

WE FOUGHT FOR IT AND WON!

SPECIAL THANKS TO ALL THE GIRLS!

9-3-69”

With the glued plate and bronzed casing, the loafer is extremely stiff, rigid, and unbendable– completely prohibiting comfortable wear or movement. Thus, its original purpose has been eliminated beyond the fact it is separated from its pair. Upon close examination inside the loafer, the red insole is likely made of felt– a nonwoven fabric (Fig. 4). Its texture is soft with high signs of wear as it is flattened, very rough around the edges, covered in dirt, and stained with splotches. The shoe’s un-bronzed inside also evidences t aging due to its rough, almost crumbly texture, discoloration, and yellow and blue paint stains (Fig. 5).

What was the I.L.G.W.U.?

Around the late 1800s and early 1900s, millions of East European immigrants fleeing from job shortages, crop failure, financial ruin, religious oppression, and political persecution arrived at the United States’ east coast, notably New York City, in hopes of finding a better life (“Immigration to the United States”). Many immigrants, particularly women, employed themselves in the emerging and labor-hungry garment industry. Despite their dreams of a better life, garment workers faced factory owners that exploited the immigrant and female lowsocial status for cheap labor and extended hours. The poor working conditions, unfair pay, and lack of voice for minorities manifested into the development of garment unions. On June 3, 1900, eleven delegates of seven garment unions congregated to form the International Ladies’ Garment Workers’ Union (I.L.G.W.U.) in hopes of improvement (“Founding”). Throughout the 18th century the I.L.G.W.U. grew to become one of the US’s largest and influential labor unions.

Scabs Versus Unity

| Figure 6: Handwritten note by Lois Hartel that was folded within the “Bronzed shoe”. |

Inside the loafer is a note from Lois Hartel, the artifact’s donor, that reads, “This shoe was ‘lost’ by a scab, who was later arrested. During the Dunkirk Lingerie Strike 1969 in Dunkirk, NY. In the materials, is the paper work for the lawsuit which was filed” (Fig. 6). The term “scab” is “American slang for a workman who refuses to join an organized movement on behalf of his trade,” according to Stephanie Smith’s published article in the journal, Key Words: A Journal of Cultural Materialism (Smith). Stemming from the 1700s as a derogatory label for those with low morality, union members adopted the term to demonstrate their resentment toward scabs (“Early Boilermaker”).

Bronzing a shoe lost by a scab further deepens and elevates the shoe’s overall symbolism and plate’s message. It is not just a celebration of better work conditions, but a celebration of the collective effort that was taken to achieve it. Smith explains how scabs were a “blemish on the social body of labour, an almost physical wound to the solidarity of workers” (Smith). Scabs were threatening to strikes and labor unions’ goals as power and voice were derived from numbers. Even with a common desire and goal, without collected effort, achievement would be near impossible. The plate’s proud words: “WE FOUGHT FOR IT AND WON! / SPECIAL THANKS TO ALL THE GIRLS!” is thus a recognition of the women who came together, fought together, and finally, won together.

It was challenging to find information on the 1969 Dunkirk Lingerie Strike the bronzed shoe is from; however, I did manage to discover details of the strike in the 1882-founded and Dunkirk, NY centralized newspaper, Observer. In the Observer, their “Retrospective” column reports past published events that occurred on the same day. In their column published on August 20, 2021, the Observer writes under “Fifty years ago — 1969”: “One hundred and twenty-five garment workers went on strike this morning at the Dunkirk Lingerie Co. plant located in the former Van Raalte building at the foot of Wright Street…A spokesman for the workers said one of the complaints is the lack of a unionized labor force” (“Retrospective”). The bronzing of the shoe and glued plate already endow the feeling of importance and immortalization of the strike’s winning day; however, with the joint context that scabs were a “wound to the solidarity of workers” and the Dunkirk Lingerie Strike had struggled with a “unionized labor force” it is reasonable to speculate that those who bronzed the loafer hoped to commemorate the unified nature of their victory (Smith; “Retrospective”).

Temporal Context & Connections

The 1969 Dunkirk Lingerie Strike’s general time period was a sort of golden age for the I.L.G.W.U. Between 1932 and 1966, the I.L.G.W.U. had grown exponentially in influence and numbers with “union’s membership…doubled in size” (“Org. New Garment”). In this 30-year golden period, the I.L.G.W.U. had “successful organizing campaigns, won significant concessions from manufacturers, and expanded the elements of social unionism” (“Org. New Garment”). The original goals and sentiments that drove the I.L.G.W.U. were not lost sixty years in but strengthened. The Dunkirk Lingerie Strike certainly fits into this ambitious and accomplishing narrative from my deciphering of the bronzed shoe as symbolic of both success and unity. My interpretation of the bronzed shoe fits accordingly to its immediate temporal context.

My hypothesis of the loafer’s symbolism can also be traced back to the I.LG.W.U. ‘s beginnings; to a broader historical context. The shoe plate’s message is not dissimilar from Clara Lemlich’s at the pivotal “Uprising of 20,000”. To explicate, on November 22, 1909, Lemlich passionately encouraged thousands of workers at NYC’s Cooper Union to endorse a general strike. Lemlich and the event’s chairman call for the crowd to take the Jewish oath and pledge their loyalty: “If I turn traitor to the cause I now pledge, may my hand wither from the arm I now raise” (“Clara Lemlich Sparks”). The 13-week general strike concluded with a successful “contract establishing higher wages for 15,000 workers” (“Timeline”). The threat of disunity to the workers’ fight is expressed clearly in both the Jewish oath and bronzed shoe’s plate. Rather it be the label of a “traitor” or a “scab”, the central idea is that a nonunified worker could break apart a labor union’s strike.

The bronzed shoe is exemplary of the I.L.G.W.U. ‘s stress on a collective effort. To union workers, scabs were in some ways as villainous as unjust factory owners; factory owners may impose poor wages, hours, and conditions, but scabs could prevent a centralized, cohesive force for action and change. Labor unions’ strength came from their numbers, an increased voice was a louder one that could gather those around and fight against those in higher power. Especially in a labor union that voiced the minority populations of immigrants and women, concentrated group effort was crucial to the I.L.G.W.U. ‘s success– thus the bronzed shoe’s proud exclamation: “SPECIAL THANKS TO ALL THE GIRLS!”

Works Cited

“Clara Lemlich Sparks ‘Uprising of the 20,000.’” Jewish Women’s Archive, https://jwa.org/thisweek/nov/22/1909/clara-lemlich.

“Early Boilermaker Publications and the Origin of Scabs.” International Brotherhood of Boilermakers, The Boilermaker Reporter: Volume 60, Number 3, 17 Jan. 2021, https://boilermakers.org/news/history/early-boilermaker-publications-and-the-origin-of-scabs.

“Founding.” History of the ILGWU, Cornell University, The Kheel Center ILGWU Collection, Aug. 2011, https://ilgwu.ilr.cornell.edu/history/index.html.

“Immigration to the United States, 1851-1900.” The Library of Congress, The Library of Congress, https://www.loc.gov/classroom-materials/united-states-history-primary-source-timeline/rise-of-industrial-america-1876-1900/immigration-to-united-states-1851-1900/.

Kheel Center for Labor-Management Documentation and Archives, Cornell University Library, ILGWU Memorabilia, 1965-2002. Collection Number: 5780 MB. Box 13, Folder 25. https://rmc.library.cornell.edu/EAD/htmldocs/KCL05780mb.html#d0e126.

“Organizing New Garment Workers.” History of the ILGWU, Cornell University, The Kheel Center ILGWU Collection, Aug. 2011, https://ilgwu.ilr.cornell.edu/history/organizingWorkers.html.

“Retrospective.” Observer, 20 Aug. 2019, https://www.observertoday.com/opinion/retrospective/2019/08/retrospective-938/.

Smith, Stephanie A. “‘Scab.’” Key Words: A Journal of Cultural Materialism, no. 4, 2003, pp. 12–16. JSTOR, http://www.jstor.org/stable/45367747.

“Timeline” History of the ILGWU, Cornell University, The Kheel Center ILGWU Collection, Aug. 2011, https://ilgwu.ilr.cornell.edu/timeline/index.html.

Author Bio: Ashley Kim ’26 is a first-year undergraduate majoring in the History of Art within the College of Arts & Sciences. Alongside Art History and her passion for critical and creative writing, she is exploring Public History, Information Science, and Fashion Studies at Cornell. She is interested in art’s societal influence and visual culture expressed through art, fashion, media, and social spaces.