This online blog post features materials protected by the Fair Use guidelines of Section 107 of the US Copyright Act. All rights reserved to the copyright owners.

Blog post by Joyce Wang

Only a century ago, most Japanese people still wore kimonos. Now, kimonos are generally only worn on special occasions while Western clothing dominates Japanese society. What events caused this shift in clothing within Japanese Culture and textiles?

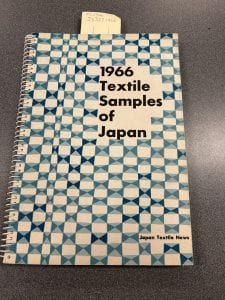

The 1966 Textile Samples of Japan Catalog

The artifact I chose to analyze is a paper spiral catalog with samples of fabrics glued inside simply titled 1966 Textile Samples of Japan. This book was made by the Osaka Textile Research Co., Ltd and was edited by the Editorial Sect of Japan Textile News and was part of a series of annual issues to display Japan’s textiles and textile technology. The book features fabrics and images of Japanese men and women in western dress shirts, women’s blouses/dresses/suits, casual wear, slacks, and men’s suits. Finally, there are advertisements of textile companies posted on the front and the back of the book, evidence that this book was meant to be used to gain investors.

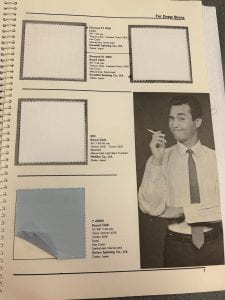

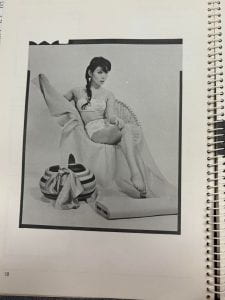

What immediately stood out to me was that the book was entirely written in English. Additionally, its language is directed to foreign investors, specifically saying that it is “an indispensable adviser for your business activities and invaluable for your own research work.” The Japanese models wore western-styled garments made out of the advertised along with makeup and hairstyles that were popular in the 1960s in the United States. My prior knowledge of Japan did not place it as a nation known for its textile industry – even less so for the manufacturing and exporting of western-styled clothing.

Emergence of Western Superiority in Japanese Textiles

To answer the questions on how this English catalog of Japanese textiles came to be, it is best to contextualize the history behind Japanese textiles.

The beginning of the shift from indigenous Japanese to western dress can be traced to a single date, January 3, 1868, or the beginning of the Meiji Restoration. During this period, Japan’s government strove to adopt western ideas in order to innovate their country’s technology and economy. Seeing how the West’s military power split up China, Japan aimed to modernize to adopt western ideology. Japan finally opened its borders to the West with the arrival of Matthew Perry. Along with implementing a constitutional government and building railroads, dress began to change. Officers’ and the shogunal army’s clothing were switched from kimonos to western-styled suits (Nakagawa and Rosovsky). Government officials and upper-class Japanese citizens also wore western dress (Slade 56).

Western-style clothing quickly became a symbol of superiority both in and outside of Japan. Within Japan, it was a symbol of being an upper-class citizen. Other countries, such as the United States, viewed Japan’s westernization as a sign that it was a superior nation in comparison to other eastern Asian countries. However, most Japanese citizens did not adopt western dress because the materials were more expensive, the construction was difficult to manufacture, and they did not last as long as kimonos (Slade 56). Even so, “[w]estern dress had become a symbol of social dignity and progressiveness, an accepted symbol of civic progress” (Slade 55).

The average Japanese began wearing westernized clothing during the World Wars when the clothing was literally labeled “smart,” “cultured,” and “civilized” (Slade 56). American-styled garments were considered superior due to the arrival of Hollywood cinema (Slade 57). After World War II, Japan was occupied by the Allied Powers– notably the US–and very quickly industrialized in the period called the Japanese economic miracle (Els Hiemstra-Kuperus et al.). During this period, textile production notably helped Japan get out of war and economic trauma. “Under the Occupation (1945-52), the textile industry was soon designated as a key sector to lead Japan’s economic recovery” (Slade 57). Furthermore, “[t]extile production made up 23.9% of Japan’s industry in 1966” which was the same year the 1966 Textile Samples of Japan artifact was published (Broadbridge 39). Although the westernization of Japanese clothing started as a superiority symbol, it quickly evolved into an economic necessity for the country.

Significance of the 1966 Textile Samples of Japan

According to the authors of the catalog in the editor’s notes, the book was created to present an “up-to-date aspect of the Japanese textile industry” with hopes to “service readers who intend to develop their textile trade with Japan.” Therefore, the book and its fabrics are effective evidence of the early days of outsourcing. In the United States, outsourcing and offshoring of manufacturing started to occur in the 1950s and 1960s but did not become mainstream until the 1970s.

The fabrics marketed towards men were business/professional-wear fabrics constructed with rigid, plain, light-colored tetoron, polyester, and cotton mixes. Meanwhile, the fabrics marketed towards women were stretchier, more colorful, and featured patterns for garments to be worn at home. It catered to the American lifestyle at the time which centered around patriarchal families where men went to work to be the family breadwinner while women were expected to be stay-at-home mothers (Kurtz).

At the beginning of each clothing section, there are descriptions written promoting new types and blends of fabrics – in particular, synthetic fabrics. The specific textiles mentioned are rayon, spun rayon, and polyester and cotton blends. This was most likely in collaboration with Japan’s technology industry which was also growing at this time (Nakagawa and Rosovsky). These cheaper synthetic fabrics allowed Japan to produce cheaper textiles for the global market that were touted for their “wash-and-wear property” and “stretch”–both terms used to describe the textiles throughout the article.

Closing Comments

This semester in FSAD1250, we had several discussions on indigenous garments that stuck out to me, such as the Indigenous Dress Theory reading and the Indigenous Fashion Theory lecture given by Shawkay Ottmann. These lectures struck a chord with me. As someone who is from a different culture but was raised in the United States, I was often embarrassed by my family members as a child because their ideology, actions, and clothing were different from my mostly white peers. As I have grown up, I have begun to question why I have subconsciously and consciously thought that western ideology and culture are superior. As a result, I have a deep interest in the history of the assimilation of western ideology into other cultures. Historical events have shown that this has occurred through traumatic forced assimilation, such as through government boarding schools, or through soft power.

In the case of Japan, I believe that the westernization of Japan and its garments occurred through fear of the West’s military and Hollywood’s soft power. Japan felt a need to “innovate” in a way that would be accepted by western nations. This included changing their style of dress from the kimono which in itself is an excellent show of innovative design as it does not rely on buckles or buttons to slacks, dress shirts, dresses, and coats (Nakagawa and Rosovsky). It brings the question on what is and what is not considered innovative in fashion.

Works Cited:

Broadbridge, Seymour A. Industrial Dualism in Japan: A Problem of Economic Growth and Structural Change. London, Routledge, 2016.

Els Hiemstra-Kuperus, et al. The Ashgate Companion to the History of Textile Workers, 1650–2000. Routledge, 1 Apr. 2016.

Kurtz, Stanley. Culture and Values in the 1960s. 2003.

Nakagawa, Keiichirō, and Henry Rosovsky. “The Case of the Dying Kimono: The Influence of Changing Fashions on the Development of the Japanese Woolen Industry.” The Business History Review, vol. 37, no. 1/2, 1963, pp. 59–80, www.jstor.org/stable/3112093, 10.2307/3112093. Accessed 8 Nov. 2020.

SCRC SME. “A Brief History of Outsourcing | Supply Chain Resource Cooperative | NC State University.” @SupplyChainNCSU, June 2006, scm.ncsu.edu/scm-articles/article/a-brief-history-of-outsourcing.

Slade, Toby. Japanese Fashion: A Cultural History. Oxford, Berg Publishers Ltd, 2009.

Author bio:

Joyce Wang is a sophomore in the College of Human Ecology, majoring in Human Biology, Health, and Society and minoring in Human Development.

Growing up in the cotton fields in Georgia as the only East Asian student in her classes, she was driven to embrace her culture despite barriers she faced. In a world history classes, her teacher repetitively emphasized that Asian countries were colonized because of their “stubbornness” to modernize. He praised Japan’s rapid westernization and reasoned that this prevented its colonization. Ever since, Joyce has challenged the idea of what is considered innovative and who gets to decide what is considered innovative.