Blog post by Rina Takaoka ’24.

This online blog post features materials protected by the Fair Use guidelines of Section 107 of the US Copyright Act. All rights reserved to the copyright owners.

Akiko Yosano, a Japanese post-classical poetess, once wrote:

“Beautiful are women’s garments

Brimming with the unuttered feelings of

women’s hearts” [1].

Needless to say, the kimono is more than just a traditional garment; Japanese women express their unique identities through their kimonos which symbolize the ideal Japanese femininity. This blog post will explore the cultural significance of a particular kimono, which was depicted in the Kyoka Momo Chidori, a woodblock-printed lookbook published in c. 1830 during the Edo period. This artifact is located in the Kroch Library Asia Collections and was created by Yanagawa Shigenobu (1787-1832), an ukiyo-e style artist and pupil of Katsushika Hokusai.

A Brief History of the Kimono

The kimono, which directly translated means “thing to wear,” is a long, sophisticated robe with wide square sleeves and tied with the obi sash. The garment is said to have been created in the Heian period (792 AD-1186) and is recognized today as a form of national dress in Japan [2]. By the Edo period (1630-1868), the garment came to be known as the kosode meaning “small sleeves” [2]. The Edo period marked the final era of traditional Japan before foreign influence; the kosode symbolized a “unifying cultural marker” that had evolved into a unisex outer garment worn by every Japanese person regardless of their distinguishing characteristics such as age and rank [2]. Each garment differed in its designs, fabrics, and techniques, and often signified one’s socioeconomic status as well as other aspects of the person’s identity, like gender and age. The term kimono was adopted more recently during the Meiji era (1868-1912) which was a period of rapid modernization [2]. The kimono symbolized a remnant of traditional Japan in a time of transitional, cross-cultural interactions.

Styling the Kimono 101

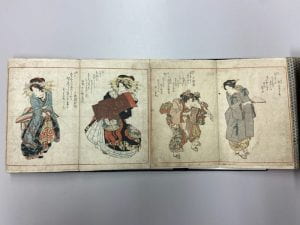

The kimono is made of a compilation of small pieces of materials produced from one rectangular piece that are all sewn together in a straight line [1]. Despite its relatively simple structure, the complexity lies within the sewing process which requires a mastery of various techniques [1]. One of the most important components of the kimono is the obi sash which is fastened at the waist and facilitates movement. Rectangular in form, the obi is made of a range of fabrics including hand-woven materials, satins, and silks, which can cost up to one million yen [1]. This variation can be seen by comparing the sashes in Figure 1: the woman on the far left is wearing a simple, brown front-tie obi while the woman on the very right is wearing a thick, floral obi tied at the back.

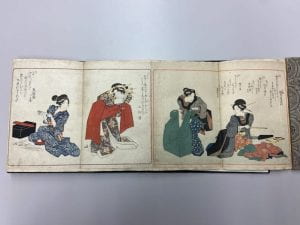

The kimono is also paired with the haori coat that is worn over the kimono proper, portrayed by the two women standing next to each other in Figure 2. This outerwear is a prerequisite for ceremonial occasions but also worn daily by both men and women, especially during the cold winters [1]. Next, the hakama skirt is worn under the haori coat. Typically made of hard pongee fabrics, the hakama skirt is similar to western skirts and pleats but much longer in length [1]. Finally, the Juban undergarment is worn under the kimono proper, creating a firm base [1]. In addition, accessories known as komono typically complete the style. Most commonly, the two-toe tabi socks made of hard fabric cotton is worn with either the zori sandals (Figure 1) or the geta wooden clogs (Figure 2) [1]. The sensu was another popular fashion item during the Edo period, which is a folding fan held by the women on the far right in Figure 2. These various elements of the kimono come together to form an elegant, harmonious style on the human body.

Embodying the Ideal Feminine Form

The kimono is an important cultural symbol, reflecting the highly gendered structure of ancient Japan. For example, the round-shaped sleeves indicate female use while the rectangular sleeves indicate male use [3]. The kimono is made of a straight-line cut, with the objective being “to create a beautiful and tense atmosphere by means of the linear effects of the garment and curvaceous effects of the body itself” [1]. The garment’s standardized cut depicts the ideal cylindrical body shape, therefore modeling the ideal feminine form [4]. To fit into the kimono, women must undergo a “correction” process known as hosei, in which gauze and towels are used as paddings to forcefully fit the body into the garment [4]. Women with thinner bodies may add extra layers of padding such as towels, while women with wider physiques may be required to flatten their breasts [4]. For this reason, all the women portrayed in the lookbook have similar body sizes and facial features to satisfy the high beauty standards.

Furthermore, the tight layers of the garment constrain the body, illustrating “notions of patience and endurance (gamman) [which] have been regarded as part of femininity training in Japan” [4]. Note that the restricting elements resemble garments from the Victorian era; the binding obi sash parallels the Western use of the corset, along with the multiple layers of clothing [4].

When being stored, the kimono is neatly folded into a perfect square shape which produces fold-lines called orime [1]. These clear-cut lines are never ironed out when being worn since the orime further indicates a well-bred gentleman or lady [1]. Hence, the kimono was a way for Edo women to manifest the ideal feminine form.

The Meaning Behind Symbols, Motifs, and Techniques

Shigenobu’s fold-out lookbook features many exquisite kimonos, displaying the use of different design elements. One of the most popular floral motifs in kimono design is the Japanese cherry blossoms, sakura, which is incorporated in Figure 1 and Figure 3. The sakura is characterized by its fragility. Its brief blooming period reflects the “transience of life” which came to be

Another motif seen in the first kimono in Figure 1 is the crane (tsuru) which signifies “one of the foremost symbols of longevity and good fortune in East Asia” [3]. Here, the kimono graphically depicts the orizuru which are paper cranes made of origami papers [5]. We also see butterflies in the second kimono of Figure 2 which was “often desired as family crest because of their elegance” [3].

appreciated during the Heian period [3].

The intricate designs of the kimono are also created from various design techniques. Popular dyeing methods include shibori-zome (tie-dyeing), roketsu-zome (wax-resist dyeing), kata-zome (stencil printing), and tegaki (hand-drawn). Indigo roketsu-zome is used in the kimono worn by the third woman in Figure 3. Here, wax is applied on cotton fabric to create a design, and the waxed area blocks the indigo dye, leaving white spaces [6]. For this specific design, the roketsu-zome method is paired with the Japanese ikat weaving technique that uses Kasuri textiles; the kasuri patterns are dyed using both the weft and warp threads called tate-yoko-gasuri, creating the indigo-dyed double ikat design [7]. Evident in its meticulous design, a lot goes into the production of the kimono. These practices have been endured for centuries, enabling Japan’s national treasure to remain at the core of its traditional culture.

References

[1] Tokyo Keizai Inc. “Glimpses of Japanese Culture: Japanese Kimono.” The Oriental Economist, vol. 27, no. 587, 1959, pp. 538-539. EBSCOhost, search-ebscohost-com.proxy.library.cornell.edu/login.aspx?direct=true&db=edsjkn&AN=edsjkn.91603V195909010P0036.19127&site=eds-live&scope=site.

[2] Green, Cynthia. “The Surprising History of the Kimono.” JStor Daily, 2017. https://daily.jstor.org/the-surprising-history-of-the-kimono/.

[3] Luu, Sophia and Ellen McKinney. “Kimono: elucidating meanings of Japanese textile artifacts for a museum audience.” Universidade de São Paulo, Museu Paulista, vol. 29. 2021, pp. 1- 45. EBSCOHost, https://doi.org/10.1590/1982-02672021v29e9.

[4] Goldstein-Gidoni, Ofra. “Kimono and the Construction of Gendered and Cultural Identities.” Ethnology, vol. 38, no. 4, 1999, p. 351. EBSCOhost, search-ebscohost-com.proxy.library.cornell.edu/login.aspx?direct=true&db=lfh&AN=4298615&site=eds-live&scope=site.

[5] Kateigaho International Japan Edition. “Kimono Patterns–1 Tsuru (Crane): A Familiar Auspicious Symbol.” Sekaibunka Publishing Inc, 2020. https://int.kateigaho.com/articles/tradition/patterns-1/.

[6] “Roketsu/Indigo Dyeing.” Traditional Kyoto. https://traditionalkyoto.com/activities/roketsudyeing/.

[7] Austin, Jim. “Kasuri History (Ikat).”Kimonoboy, 2018. https://www.kimonoboy.com/kasuri.html.

Shigenobu, Yanagawa. Kyoka Momo Chidori (One Hundred Plovers with Comic Verses), 1830.