Blog post by Colette Rose Jarrell ’25

This online blog post features materials protected by the Fair Use guidelines of Section 107 of the US Copyright Act. All rights reserved to the copyright owners.

In 1973, The New York Times pronounced the t-shirt as “the Medium for a Message” (Taylor). At the time, t-shirts were newly emerging from their historic state as undergarments into a blank slate for designers and activists to advertise and disseminate information about pressing social issues (Harris).

Members of Cornell’s Student Homophile League (SHL), the queer student group at the time, took advantage of the t-shirt’s political power and created three shirts for their own cause. According to records in Cornell University Library’s Human Sexuality Collection, withing the Division of Rare and Manuscript Collections, the students screen-printed and sold t-shirts as a means to raise money to attend the first gay pride march after the Stonewall riots in 1970. Primarily, the founding of the SHL was fundamental in the t-shirts’ creation, and their use of gay symbols in the shirts’ designs was instrumental in their message’s delivery.

Founded by Jearld Moldenhauer on May 10, 1968, Cornell’s Student Homophile League became the second queer student organization in the United States (Beemyn 205). Around 1969, the SHL began working with the Students for a Democratic Society (SDS) which provided them with more resources, specifically a leftist printing company that allowed them to print informational flyers and newsletters and spread them around campus (Beemyn 218). This recognition of the importance of disseminating information connects with the later creation of the three t-shirts.

In 1970, the Student Homophile League changed their name to the Cornell Gay Liberation Front (GLF) in order to be “a little more confrontational” (Beemyn 220). The word “homophile” had been popular in the 1950s and 1960s because it detached the sexual aspects of gay people’s identities which made the public most uncomfortable (Cantwell, Hinds and Carpenter). However, members of SHL concluded the word was passive and outdated. In addition to the name change, the GLF credits The Black Liberation Front for making them a more forceful and active student group after the Willard Straight Occupation, the momentum of which likely inspired them to join demonstrations wearing their hand-made t-shirts (Beemyn 220).

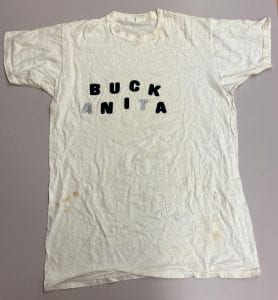

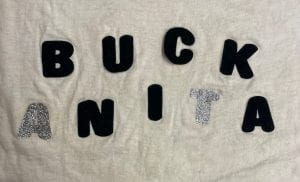

All three t-shirts use the principle of emphasis by placing their designs on a neutral background. Of the three, I was first drawn to the shirt that displayed the words, “Buck Anita” in black and silver glitter iron-on letters. The contrast between white, black, and unexpected glitter invites viewers to read and react to the message. Unity is created through the organic shapes of the font and the alignment that is not parallel or arranged on a grid, but instead is slightly curved. The glitter is created by small, almost imperceptible, points of white and gray that reflect light and, altogether, breaks the rhythm of stark colors. Although I believe they used the glitter letters out of necessity (due to limited number of letters within a pack), the design element creates an informal symmetrical balance.

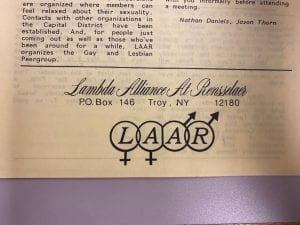

In the Cornell LGBT Coalition records, I discovered that NYSCGO (New York State Coalition of Gay Organizations) was founded in 1971 when gay organizations from around Upstate New York gathered at Cornell to hold their first conference. However, the groups really began working after 1974 when they finished the first comprehensive list of member organizations and were especially active around 1977 when the majority of their meetings and demonstrations were held (NYSCGO). The lambda’s history as a symbol for queerness and activism began when it was adopted by the Gay Activists Alliance in 1970. Inspired by its scientific and mathematical definition, the lambda symbolized “a complete exchange of energy––that moment or span of time witness to absolute activity” (Gay Activists Alliance).

The last shirt stands out because of its interesting overlapping and orientation of the gender symbols. Because of Gestalt’s Law of Pragnanz, the abstract figure is seen as four geometric circles, but because of silk-screening’s nature, they were created all at once. Unity and rhythm are created by the consistency in shape and size, as well as the informal symmetrical balance that is only offset by the crosses and arrows to represent two sexes. The interlinking pattern is symbolic of the common goals of people within the group, despite differences of gender and sexuality.

Although the gender symbols were popular in the 1970s, in historic photos of gay pride banners and posters, they were most often used separately (Solomon). However, while searching through the archives of the gay organization, Lambda Alliance at Rensselaer, I came upon a similar orientation of the gender symbols from a magazine or newsletter that they created in 1984 (visible in Figure 9). Since the t-shirt made by Cornell SHL students before 1984, it is possible that the student organizers created the new interlocking design themselves.

The most pressing question to come from my research is whether the Cornell records are accurately dating the t-shirts as being made between 1970 and 1971. If the shirts were intended to be sold, I believe that it would make more sense for them to be sold when the subject matter of the shirts, Anita Bryant and NYSCGO, were well-known and popular which was more around 1977 than 1970.

When grappling with physical objects with an unsettled history, it has been a pleasure to imagine the various contexts and embodiments of the t-shirts: to imagine the revolutions that were waged while wearing the t-shirts, the communities that came together while wearing the t-shirts, the streets that were marched, and the chants that were sung. Fashion has and always will be a powerful form of protest.

References

Beemyn, Brett. “The Silence Is Broken: A History of the First Lesbian, Gay, and Bisexual College Student Groups.” Journal of the History of Sexuality, Vol. 12, No. 2, 2003, pp. 205-23.

Cantwell, Christopher, Stuart Hinds and Kathryn Carpenter. “The Homophile Movement.” 2017. Making History. University of Missouri-Kansas City’s Public History Class. https://info.umkc.edu/makinghistory/the-homophile-movement/.

Gay Activists Alliance. “Lambda.” NYPL, Manuscripts and Archives Divison, Gay Activists Alliance Records, 1970. Flyer.

Haider-Markel, Donald P. The Oxford Encyclopedia of LGBT Politics and Policy. Oxford University Press, 2021.

Harris, Will. “The History of the T-Shirt.” n.d. Real Thread. https://www.realthread.com/blog/history-of-the-tshirt.

Johnston, Laurie. “Homosexuals Plan Educational Drive.” The New York Times, 19 June 1977, 35.

NYSCGO. “Archival Records of Meetings, Flyers, and Newsletters for the New York State Coalition of Gay Organizations.” Cornell Lesbian, Gay, Bisexual, and Transgender Coalition records, 37-6-1589, Box 10 Folder 60.

Rinne, Joel. “Upstate New York Prepares to Greet Anita.” Gay Light, September 1978, pp. 1.

Solomon, Andrew. “The First New York Pride March Was an Act of ‘Desperate Courage’.” The New York Times. 27 June 2019. https://www.nytimes.com/2019/06/27/nyregion/pride-parade-first-new-york-lgbtq.html.

Taylor, Angela. “The T-Shirt Has Become the Medium for a Message.” The New York Times. 17 August 1973, pp. 36.

Figure 1-8: Cornell Lesbian, Gay, Bisexual, and Transgender Coalition records, 1967-1999.

Collection Number: 37-6-1589. Box 8.

Figure 9: Cornell Lesbian, Gay, Bisexual, and Transgender Coalition records, 1967-1999.

Collection Number: 37-6-1589. Box 10 Folder 54