Jerry Bertoldo

Infestation with internal “worm-like” parasites (nematodes) can be a significant drain on growth rates for young stock and milk production particularly in first lactation heifers. Totally confined livestock are rarely bothered with nematodes. Newborns left on bedding packs infrequently bedded and previously occupied by shedding adults, however can be at risk of infection at an early age.

Internal parasites are economically the most important. Nematodes and coccidia have by far the most important economic impact of all parasitic diseases in the Northeast. Coccidia, tiny single-cell organisms, unfortunately are not controlled by any wormers. Coccidial control products such as Corid®, Bovatec®, Deccox® and Rumensin® must be used. Coccidiosis is a serious parasitic problem in young animals, but usually not after six months of age when resistance normally develops.

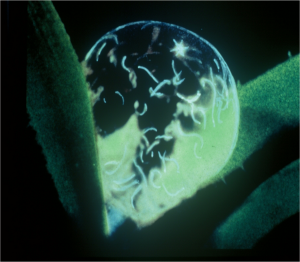

The most damaging part of the life cycle of nematodes occurs in the abomasum and intestines. As a result, diarrhea and poor feed efficiency can be seen. Deficiencies in energy, protein and micronutrients (vitamins and minerals) can occur depending on the severity. Mild cases may only affect the level of milk production a pound or so or the growth of young stock by a tenth or two of a pound of weight gain per day. Heavy infestation leads to poor body condition, faded rough hair coats, sickness, infertility and possible death in younger animals. Some nematode species create problems in the respiratory tract leading to coughing and sometimes pneumonia.

Subclinical infection not easy to see. Subclinical infection, with subtle health problems and progressive loss of productivity, is the biggest issue. By far, internal parasitism is the most difficult to judge as far as the risk and need for action. Ironically, it is generally the most costly form occurring on the dairy.

What factors need to be considered in evaluating the threat of infection and potential economic loss from “worm-like” parasites?

- Age. The younger the animal the less resistance it has.

- Stage of milk production. Fresh heifers (<100 DIM) are the most heavily impacted (reduced milk and body condition loss) of early lactation cows carrying significant worm loads.

- Pasture contamination. 99% of all pastures supporting cattle for grazing or exercise are contaminated. Period. Intensity of contamination is the only question! Any lot with edible vegetation can be a source of infection. Frequent (<3 days use per lot) pasture rotation with a return after 10 days or more allows for the maximum destruction of infective larvae by a combination of sun, dung beetles and drying. Winter freeze-kill cannot be taken as 100% effective.

- Stocking rate. Worm eggs and larvae have lower survival rates when manure is distributed over a larger area. Heavy manure build up assures greater infective larvae numbers and exposure to cattle.

- Weather. Warm and dry increases kill rates over damp and cool.

- Nutrition. Parasites prefer animals that are undernourished.

- Immune status. All animals have a limited ability to build resistance against internal parasites. This never approaches the degree acquired against viruses and bacteria, however. Poor nutrition, stressful times, the calving period and coincidental diseases lower the immune status.

- Grazing environment. Grazing during lactation and rotational grazing of all ages present the highest risk of infection. Grazing during the dry period and access to an exercise lot with some grass offers moderate risk. Cows on dirt dry lots without grass are at low risk. Total confinement and concrete dry lots have very little contamination potential. Dew covered grass holds the most infective larvae (in the water droplets) of any vegetation in the pasture.

Deworming strategies should vary by age.

There are two deworming strategies for adult cattle: the individual cow and the seasonal herd approach. Both require monitoring by fecal exam to determine contamination levels in the environment. Low contamination levels may require minimal or no treatment. Unfortunately, this cannot be judged by just looking over the animals.

The individual approach. (This strategy includes first calf heifers.)

- Cows in high and moderate contamination situations are treated at freshening and again 6 weeks into lactation.

- Low contamination level cows are treated only at freshening.

- Environments with little or no potential risk require no treatment only monitoring.

The seasonal treatment approach.

- All springers and cows in high and moderate contamination situations are treated in late November to early December and again 6 weeks after turnout onto grass.

- Low contamination level cows are treated in the late fall only.

- Environments with little or no potential risk require no treatment only monitoring.

Approach to young stock.

- Less than 300-400 lbs.: treat 3-4 weeks after turnout and again 3-4 weeks later

- Between 400 and 800 lbs.: treat at turnout, again 3-4 weeks later and a third time 3-4 weeks later

- Greater than 800 lbs.: treat at turnout and 4-5 weeks later

- NOTE: Any heifer treated in the late fall does not need deworming at turnout

Young stock under 300-400 lbs in the spring are not considered to have been exposed to parasites. The cycle of nematodes varies with the age of the animal. In younger heifers the cycle is 3-4 weeks as opposed to 6-7 weeks in the adult. This explains the timing differences between treatments by age.

Egg shed does not begin until about 40 days after normal spring turnout and usually slows dramatically by July 1st in our climate. This explains the treatment recommendation weeks after turnout. This deworming is designed partly to keep pastures from further parasite build up.

Whether you have your own adult cattle or young stock on pasture or just raise heifers utilizing some grazing, there is a good deal of trial work to show the benefits of a strategic deworming program. It is important to note that pastures will never clean up from worm contamination while in use if these programs are not used.