Ticks and tick-borne diseases have become a significant public health issue in New York. Why should you worry about ticks? Well, some spread certain diseases to humans, and some could even infect your pets and livestock. The purpose of this blog post is to give you information on a few different types of ticks, how they can affect you, and how you can manage them.

The Life Cycle of a Tick

- Larva: The tick larva is about the size of the period at the end of this sentence. They are almost impossible to find on your body but have not been proven to transmit tick-borne illness.

- Nymph: The nymph is the size of a poppy seed. Nymphs cause the majority of Lyme disease infections in people. Because of their very small size and painless bite, they are generally not detected. Nymphs are most active in the late spring and summer months.

- Adult: Adult ticks are roughly the size of a sesame seed. Due to their small size and flat shape, they can be difficult to find on your body. Adult ticks feed and mate primarily on deer. You may also find adult ticks on dogs, horses, and domesticated animals.

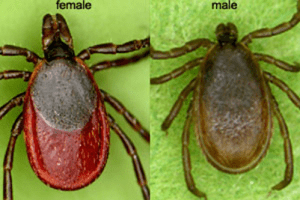

Blacklegged Tick (A.K.A: Deer Tick)

The blacklegged tick (Ixodes scapularis) is a notorious biting arachnid named for its dark legs. Blacklegged ticks are sometimes called deer ticks because their preferred adult host is the white-tailed deer. This tick is of medical importance because of its ability to transmit Lyme disease and anaplasmosis.

Deer ticks are not out in the middle of your lawn, they live where yards border wooded areas, ornamental plantings and gardens, or anywhere it is shaded and there are leaves with high humidity.

Asian Longhorned Tick

The Asian Longhorned Tick ( Haemaphysalis longicornis) is a newer pest that was reported in the United States for the first time in 2017. While it has been reported that this tick has been reported to transmit diseases to humans, it would also be wise for farmers to keep an eye on their livestock (particularly: cattle, sheep, and horses). Risks to livestock include tick-borne theileriosis and a malaria-like disease that results in anemia. Symptoms of tick-borne diseases in livestock can include fever, lack of appetite, dehydration, weakness and labored breathing. The Department of Agriculture and Markets encourages livestock owners and veterinarians to also be vigilant for unusually heavy tick infestations. If longhorned ticks are suspected, farmers should consult with their veterinarians and contact the New York State Department of Agriculture and Markets Division of Animal Industry at 518-457-3502 or dai@agriculture.ny.gov.

Asian Longhorned ticks live in meadows and grassy areas near forests.

Lone Star Tick

The Lone Star tick (Amblyomma americanum) gets its name from the single silvery-white spot located on the female’s back. These ticks attack humans more frequently than any other tick species in the eastern and southeastern states. Lone star tick bites will occasionally result in a circular rash, and they can transmit diseases. It is essential that lone star tick removal start immediately. This tick is a vector of many dangerous diseases, including tularemia, Heartland virus, Bourbon virus and Southern tick-associated rash illness (STARI). Great care should be exercised when removing embedded ticks because their long mouthparts make removal difficult. The mouthparts are often broken off during removal which may result in secondary infection.

The Lone Star tick is found in wooded areas, especially young second growth forest with dense underbrush, but it is also found in scrub, meadow margins, hedge rows, cane breaks, and marginal vegetation along rivers and streams. Upland oak-hickory forests will, normally, support large numbers of Lone Star ticks and be suitable for greater tick longevity. The largest numbers of adult and nymphs are most commonly found between the meadows and main forest body.

Dog Tick

The Dog Tick (Dermacentor variabilis) feed on a variety of hosts, ranging in size from mice to deer, and nymphs and adults can transmit diseases such as Rocky Mountain Spotted Fever and Tularemia. American dog ticks can survive for up to 2 years at any given stage if no host is found.

Their habitat includes wooded areas, abandoned fields, medium height grasses and shrubs between wetlands and woods, and sunny or open areas around woods.

Management

How to Remove a Tick:

- Using tweezers, grasp the tick as close to the skin as possible

- Gently pull the tick in a steady, upward motion

- Wash the area with a disinfectant

When trying to remove the tick:

- DO NOT touch the tick with your bare hands

- DO NOT squeeze the body of the tick as this may increase your risk of infection

- DO NOT put alcohol, nail polish remover or Vaseline on the tick

- DO NOT put a hot match or cigarette on the tick in an effort to make it “back out”

- DO NOT use your fingers to remove the tick

Creating Tick Free Zone:

Understand that ticks can be found in other places besides wooded areas, and although it may not be possible to create a totally tick-free zone, taking the following precautions will greatly reduce the tick population around your home and around your livestock.

- Cut down brush and weedy areas of pasture where possible. If this is impractical on your farm, at least cut back overgrown areas near the barn and other commonly used structures

- Keep your livestock ,such as sheep, sheared

- Remove leaf litter, brush and weeds at the edge of the lawn

- Restrict the use of groundcover, such as pachysandra in areas frequented by family and roaming pets

- Remove brush and leaves around stonewalls and wood piles

- Discourage rodent activity. Clean up and seal stonewalls and small openings around the home

- Manage pet activity; keep dogs and cats out of the woods to reduce ticks brought into the home

- Use plantings that do not attract deer (contact your local Cooperative Extension or garden center for suggestions) or exclude deer through various types of fencing

- Move children’s swing sets and sand boxes away from the woodland edge and place them on a wood chip or mulch type foundation

- Trim tree branches and shrubs around the lawn edge to let in more sunlight

- Guinea hens are natural tick-eaters and can be useful especially on small properties for tick control; however, they can be loud and disruptive

- There are many different products on the market, with different ingredients, concentrations and effectiveness. The most effective contain DEET, Permethrin, Picaridin, or oil of lemon eucalyptus. If you decide to use one, be sure to follow label directions and apply repellent carefully

- DEET (the label may say N,N-diethyl-m-toluamide) comes in many different concentrations, with percentages as low as five percent or as high as 100 percent. In general, the higher the concentration the higher the protection, but the risk of negative health effects goes up, too. Use the lowest concentration that you think will provide the protection you need.

- Products containing permethrin are for use on clothing only, not on skin. Permethrin kills ticks and insects that come in contact with treated clothes. Permethrin products can cause eye irritation, particularly if label directions have not been followed. Animal studies indicate that permethrin may have some cancer-causing potential. Permethrin is effective for two weeks or more if the clothing is not washed. Keep treated clothing in a plastic bag when not in use.

- Picaridin (also known as KBR3023) and oil of lemon eucalyptus were registered for use in New York State in 2005. Both repellents have been shown to offer long-lasting protection against mosquito bites but there are limited data regarding their ability to repel ticks.

Farmers, spring is right around the corner! As you are working with your livestock (especially sheep, goats, and cattle) every day, take the time to check them for ticks. Good places to inspect include the ears, the groin, and behind the jaw. It might be of good practice to keep a pair of tweezers in the first-aid kit in your barn. Also, if you decide to use chemicals near or on your livestock or if you have to get them treated, be aware of withdrawal periods.

If you would like to evaluate a tick to discover the type or if it is carrying a pathogen, The Parasitology Section of the Animal Health Diagnostic Center at Cornell University is a full-service parasite diagnostic laboratory capable of diagnosing infections in domestic and wild animals. You can check out their website by following this link: https://www.vet.cornell.edu/animal-health-diagnostic-center/testing/protocols/tick-evaluation. However, if you believe that you are infected, do not wait for results of this testing to consult a physician. Also, positive results do not necessarily indicate that an infection has been transmitted.

Have questions? Feel free to reach out to our office: 518-272-4210

Sources:

https://globallymealliance.org/about-lyme/prevention/about-ticks/

https://www.health.ny.gov/publications/2825/

https://www.pestworld.org/pest-guide/ticks/lone-star-ticks/

https://www.pestworld.org/pest-guide/ticks/blacklegged-deer-ticks/

https://nysipm.cornell.edu/whats-bugging-you/ticks/what-do-ticks-look/

http://www.cvbd.org/en/tick-borne-diseases/about-ticks/tick-species/american-dog-tick/habitat/

http://www.cvbd.org/en/tick-borne-diseases/about-ticks/tick-species/lone-star-tick/habitat/

https://tickencounter.org/prevention/identify_and_eliminate_tick_habitat