LeCavalier, an architect, urbanist, and educator shares thoughts on public life and value-integrated design practices, alternative models and trajectories for development, and questions we can ask as producers of our society and surrounding landscapes.

Associate Professor of Architecture Jesse LeCavalier, a new member of the AAP faculty as of this year, uses the tools of urban design and architecture to research, theorize, and speculate about infrastructure and logistics. LeCavalier’s often collaborative work is recognized for exploring the spatial and aesthetic dimensions of logistics as well as possible applications of a “middle-out” (versus top-down or bottom-up) approach to urban design that proposes concepts for regenerative urban systems that support collective wellbeing. LeCavalier is the author of The Rule of Logistics: Walmart and the Architecture of Fulfillment (University of Minnesota Press, 2016), and his design work has been recognized by the Sudbury 2050 urban design competition, the MoMA PS1 Young Architects Program, the Oslo Triennale, and the Seoul Biennale. His project, Brooklyn Amenity Utility, will be featured in an upcoming exhibition, A Section of Now: Social Norms and Rituals as Sites for Architectural Intervention running November 13, 2021-May 1, 2022 at the Canadian Center for Architecture. Prior to joining the AAP faculty, LeCavalier was the Daniel Rose Visiting Assistant Professor at the Yale School of Architecture (2017–19) and the 2010–11 Sanders Fellow at the University of Michigan. His work has appeared in Thresholds 49: Supply, AD: Machine Landscapes, Cabinet, Public Culture, Places, Art Papers, and Harvard Design Magazine.

You are an architect and urban designer, how did you come to logistics and infrastructure planning?

As an architect and urbanist, I became interested in logistics through a larger interest in the possibilities and challenges of infrastructure in the context of urbanism. Questions of logistics have increasingly occupied the public imagination in the past 18-months but I would say that they have rarely intersected with the design disciplines in self-conscious ways — and yet, both infrastructure and design offer a glimpse of the systems that shape so much of the world. There is an amazing amount of intelligence and ingenuity in the logistics industry but it is also, for the most part, an extractive industry predicated on the brutal logics of capitalism. The design disciplines are spaces where alternative possibilities can be expanded through the development of parallel conditions that imagine logistics and infrastructure through different value systems.

In a recent article in Thresholds 49, you argue that logistics is about who gets what and how they get it. Is this what you mean by value systems through which designers can imagine alternative possibilities for infrastructure?

Logistics and infrastructure are pressing societal concerns, and, they condition the built environment. The disastrously uneven international rollout of the COVID-19 vaccine is one recent example. Initially, this may not seem like an architectural or urban design question, but understanding the embeddedness of design decisions in public life and publicly funded systems is critical to both analyzing and reimagining how resources are distributed and access is constituted. Moreover, as corporations continue to consolidate access to resources and data, the content of the buildings that support such systems is effectively us. And so, if the logistical landscapes that support “just-in-time” fulfillment are a reflection of the society that produced them, we need to ask: Are we happy with that image? Is it accurate in its reflection of our collective needs, desires, hopes?

This said, I am not asking for a representational or geometrically formal response from architects and urban designers, but rather one that recognizes the logics of logistics and infrastructure and might be willing to surrender some of the aspects of what we call architecture and the city in order to find other pathways.

Alimentary Urbanism, your urban design competition entry for Sudbury 2050, begins with a simple but fundamental question: What would a city be like if its infrastructure was directed toward nourishing and supporting its population? How does your work answer, or begin to answer this question?

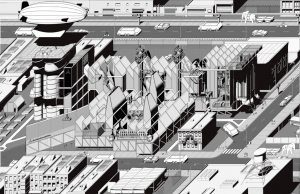

My team and I were interested in looking at the ways that a city characterized by a linear, extractive economy (Sudbury was one of the world’s primary suppliers of nickel) could transition to a circular one. Our proposal started by challenging the common assumption that private investment is the primary driver of urbanism. We did this with a series of proposals for regenerative economic practices: food cultivation; energy production; reforestation and timber production; as well as new forms of education, healthcare, outreach, and recreation. The idea is that these economic drivers can become catalysts for repurposing and expanding the area’s robust rail network to in turn redistribute new assets throughout Sudbury’s diverse neighborhoods. A series of new rail spurs sponsor community infrastructure nodes that provide essential services as well as cyclical recreational, social, and enrichment opportunities in the form of a fleet of mobile programs.

The project relied on a strategic framework that imagines a middle-out approach to urban design and governance. Top-down models of state redevelopment mandates have a bad history in Sudbury while bottom-up approaches depend either on market forces or individual ingenuity. Instead, this approach builds new cooperative community organizations that support incremental, deliberate, and collective self-determination. Some of these interests build on a prior project done in collaboration with Tei Carpenter, Dan Taeyoung and Chris Woebken called Intentional Estates Agency for the Oslo Architecture Triennale on the idea of “degrowth.”

Your book, The Rule of Logistics: Walmart and the Architecture of Fulfillment, shows how the world’s largest retailer redefined architecture, subjectivity, and sovereignty by moving merchandise and information through space and time. What inspired you to write it? Any surprises while researching or writing?

Until its unseating by Amazon, Walmart was the largest retailer of its kind — it had the most employees, the most revenue, and so on. What intrigued me was that they got to that point by thinking about their operations through logistical systems, but also with an awareness that their thousands of buildings are physical components of those systems. So here you have architecture enrolled in this massive logistical regime and at a certain point, these buildings stop being thought about in all the ways that design often is. Architecture became a logistical system for Walmart. This case, and those like it ask: How is architecture then conceptualized through a collective logistical approach? And, how are those buildings located? Who works in them and in what conditions? What does it mean to be coordinating all of this from northwest Arkansas? These were some of the motivating questions of the book. Each level was full of surprises, from bar code birthdays to unexpected stories or connections: chewing gum, satellites, missionaries, pocket watches, prairie style, Swedish traffic laws, pop-tarts, hurricanes, for example.

Logistics planning addresses frictions in order to streamline supply chains for large retailers, among other industries. While efficiency has its benefits, do you think it could lead to increased overconsumption? How might we use logistics planning for good, or make distribution and/or consumption more sustainable?

I am interested in the spaces that are more immune to the pressures of logistics. Which human activities suffer when they become more efficient? Conversely – and this is something we are currently exploring in my studio, Logistical Frictions, this fall at AAP NYC – how might we recast inefficiency as something generative? I think part of our challenge is in how we frame our problems and ask our questions. Our goal as a community of designers might be to ask more fundamental questions, for example, not how to make consumption more sustainable but rather how we might help bring about a world where the notion of “consumption” is altogether different.