by Arielle Rochelin, PhD Student, History

In 1999, the city of Atlanta put an end to the infamous street party known as Freaknik. Municipal authorities blamed the booty-shaking women, dope-boys, booze heads, and tricked-out Cadillacs for clogging the streets and bringing the city to a standstill. To this day, this is the memory of Freaknik that endures – one that equates the fête with black delinquency and that serves as a cautionary tale for Atlanta’s officials. The Southern city that pronounced itself “too busy to hate” had clear limits to its liberality.

In equating the spring break extravaganza to black misbehavior, city officials reduced the party’s memory to spectacle. The festival’s name, a fusion of the era’s popular Freak dance and the word picnic, certainly did not help to sanitize its reputation. Tales of Freaknik neglected the festival’s humble beginnings and glossed over the behaviors of city officials and residential bystanders. And this was not by chance. Freaknik’s negative reputation was engineered by Atlanta’s systems of residential segregation and by the city’s rhetoric of black immorality.

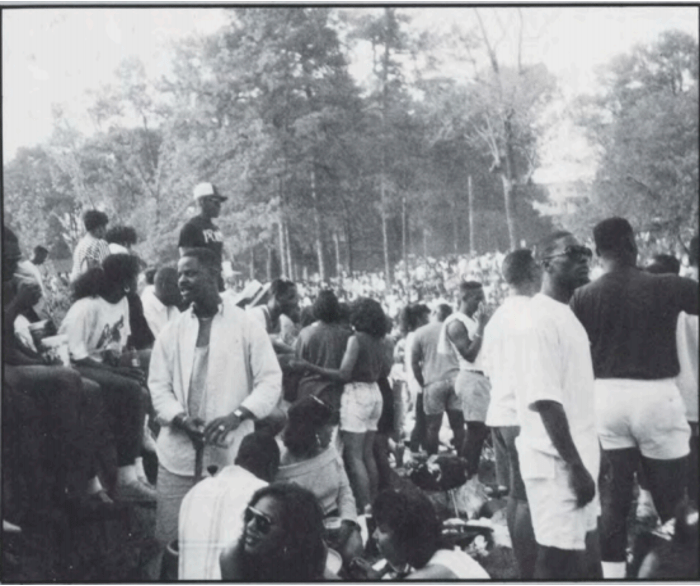

In the eighties, the spring break gathering was patrolled through space. Patterns of residential segregation kept black people and black cultural knowledge within specific neighborhoods. Congregants who gathered at Washington, Adams, and Piedmont Park to eat, drink, dance, flirt, and listen to good music, like in the picture above, were partying at sites that were separate from white suburbia. Atlanta’s suburbanites never knew, and never cared to know, about Freaknik’s existence because it operated outside of their purview.

Once Freaknik spilled out onto city streets and highways, it became visible to a larger audience. In other words, the party became noticeable when it disrupted the flow of white lives. Police officers were increasingly used to keep guard over the ballooning number of black partyers. Metro-Atlantans also became more vocal in their opposition to Freaknik and they used the press and the language of lawlessness to justify their discontent. Their strategy was not new. In fact, the racialized narrative of criminality had its roots in slavery, but it was remodeled during the Reagan era.

Reagan combined the binding forces of hyperpatriotism and moral Christianity with the excluding forces of disdain for urban poverty and civil rights to establish a narrative that declared drugs a threat to national security. By extension, he villainized the dark complexioned inner-city, the supposed repertoire of the drug trade, as the primary enemy of the American state and its black residents as the principal adversaries of public order. In essence, he further bonded blackness to criminality. Later on, Freaknik dissidents would weaponize this same moral logic to paint the party as a threat to the rule of law.

Yet, their version of events severely cheapens Freaknik’s history. Just like the Reaganomic claims of black urban delinquency have been contested, so too must Freaknik’s legacy be reconsidered. The sexually suggestive behaviors were certainly a part of the festivities, but they should not receive the bulk of the historical attention. Freaknik should be remembered for its virtues as well as its vices. At its core, and despite its shortcomings, it represented a cultural phenomenon for the black community that bolstered Atlanta’s reputation as Black Mecca throughout the United States.

Primary Sources

Spelman College, Spelman Reflections (Atlanta, Georgia: 1989), 83, Atlanta University Center Archives,

Secondary Sources

Allen, Frederick. Atlanta Rising: The Invention of an International City 1946-1996. Marietta: Longstreet Press, 1996.

Kruse, Kevin. White Flight: Atlanta and the Making of Modern Conservatism. Princeton, NJ: Princeton University Press, 2007.