by Cameron Tardif, PhD Student, History

While waiting at a bus stop in April 1989, sixteen-year-old Johnny Bates was shot and killed for his new Air Jordan sneakers. Only a month later, fifteen-year-old Michael Eugene Thomas was strangled by his friends for his pair. Bates and Thomas were but two victims killed over their prized kicks. Following their release in 1985, the Air Jordan emerged as a racialized marker of social status and was often understood as being associated with urban gangs and crime.

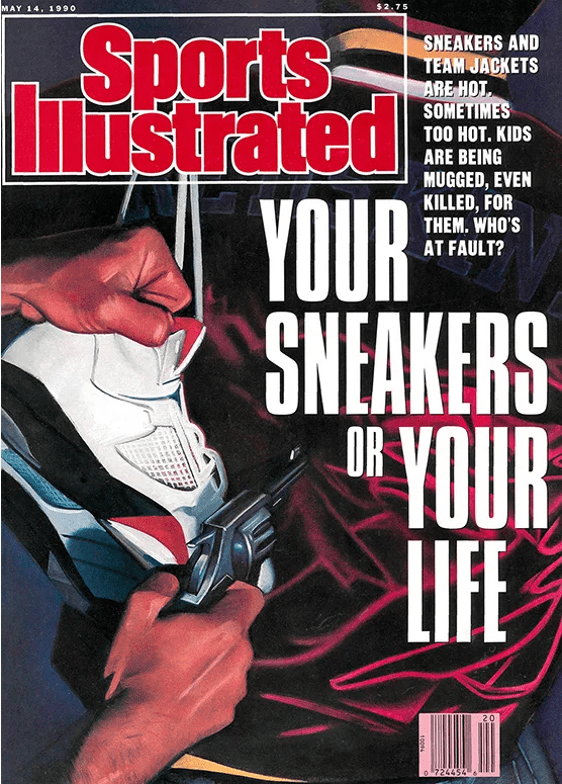

Sports Illustrated, May 14th, 1990.

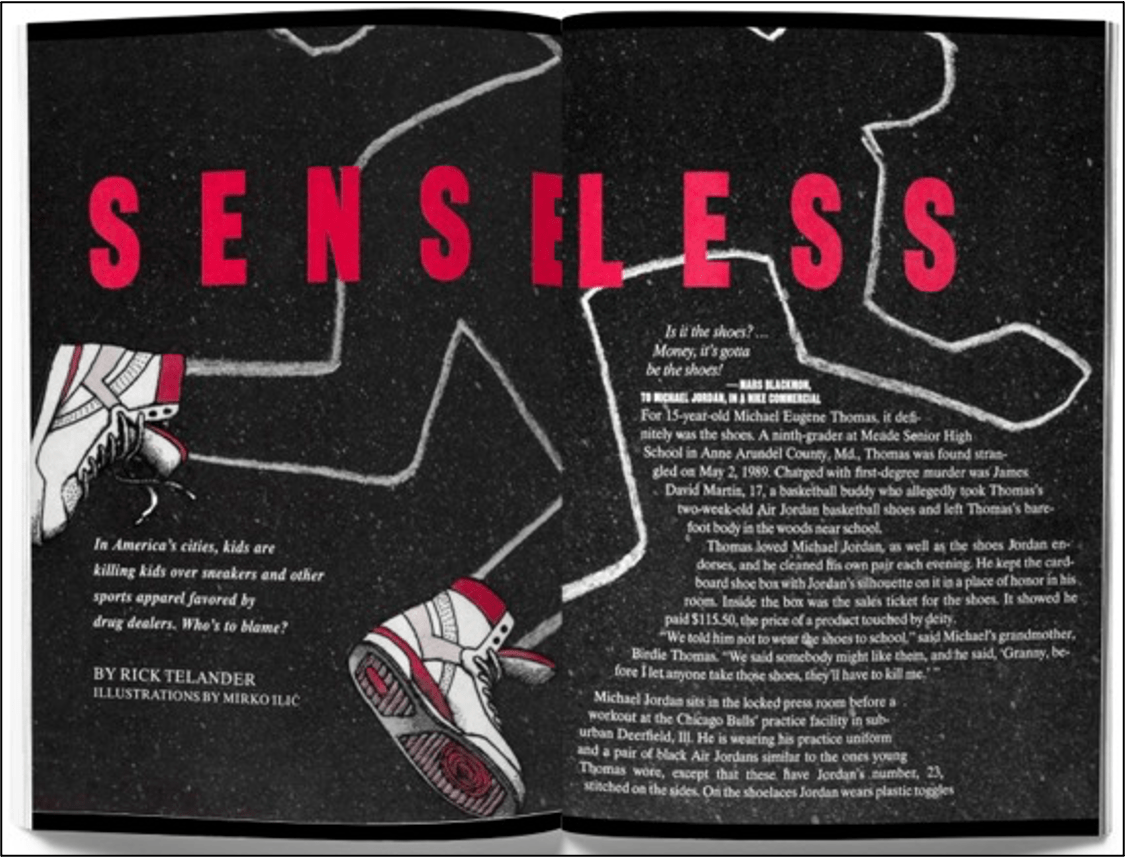

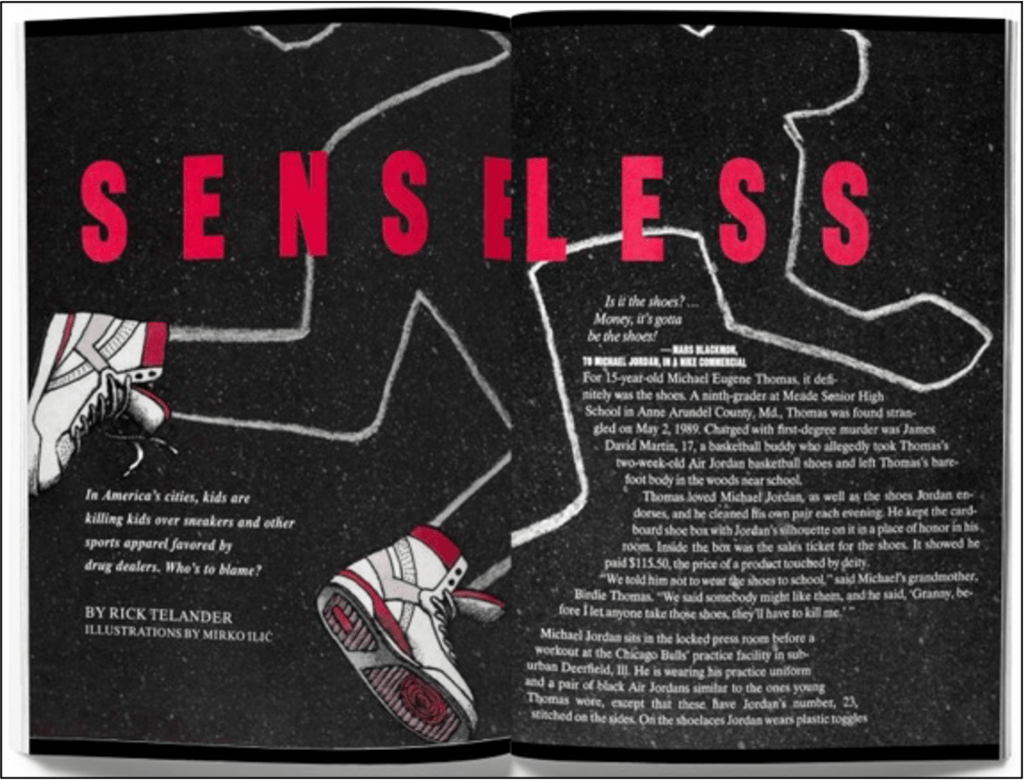

Following the death of Bates and Thomas, the May 14th, 1990 cover story of Sports Illustrated sought to highlight the slew of robberies, assaults, and murders connected to athletic merchandise, specifically the Air Jordan. In the accompanying story titled “Senseless,” Rick Telander posed the question: “In America’s cities, kids are killing kids over sneakers, and other sports apparel favored by drug dealers. Who’s to blame?”

In seeking culpability, Telander aligned himself with most national discourse by filtering his reporting through lenses of celebrity culture and neoliberal consumer capitalism and lay the blame on Michael Jordan and Nike. In a perverse rendering of Michael Eugene Thomas’s death, the imagery of Telander’s article featured a chalk outline of a body wearing the famous sneakers. In actuality, Thomas was discovered in a wooded area near his school in Anne Arundel County, Maryland, fully clothed but barefoot. The image used in Sports Illustrated offers a quick glimpse into the dangers that consumers associated with the shoe. However, this rendering functions to center the Air Jordan – and therefore Michael Jordan and Nike – while erasing the actual victim. By inverting the actual crime, media coverage obfuscated Black victims and the array of social issues that lie behind the sneaker crimes, instead keeping Jordan and the sneaker visible.

Once the shoe hit markets, Nike and Michael Jordan harnessed the power of consumer capitalism to transform the sneaker into an object of cultural capital and social identity. The signature red, black, and white sneakers generated over $130 million in revenue in their three years and by 1995 helped triple the value of the athletic footwear market from $5 billion to $14 billion. Originally, the shoes retailed for $64.95, but by 1989 the Air Jordan sold for $115. The dramatic increase in value is partly a result of a targeted advertisement campaign that featured Mars Blackmon, Spike Lee’s character from She’s Gotta Have It (1986), that hit the airwaves in the late 80s. In one commercial, Blackmon suggested that Jordan’s on-court success was a direct result of the shoes, famously asking: “Yo Mike, what makes you the best player in the universe?” and ultimately deciding, “It’s gotta be the shoes!”

Both national media coverage and scholarship have continued to analyze athletic apparel crimes through filters that accuse Jordan and Nike of using marketing to exploit a Black “underclass.” However, local media presented different arguments, often parroting the racialized political themes of the 1960s, 70s, and 80s, that mythologized Black youth and emphasized disinvested inner cities, welfare queens, urban crime, and broken Black families. Sgt. Thomas Suit, the detective investigating Thomas’s death, summarized these points when he told reporters that the wave of sneaker-induced crime was “a sign of our poor times.”

Sources

Telander, Rick. “Senseless.” Sports Illustrated, May 14, 1990.

Lazenby, Roland. Michael Jordan: The Life. Little, Brown, and Co.: 2014.

Cameron Tardif is a PhD student studying 20th century United States and Canadian history. Focusing on sport as spaces where race and power are made and negotiated, his research uses athletics as a lens to explore larger historical questions and themes including empire, citizenship, diaspora, and borders. His dissertation, tentatively titled Chasing Canaan: The United States, Canada, and the Athletic Quest for a Racial Promised Land, unravels the athletic experiences of transnational Black, Asian, and Indigenous athletes along the US-Canada border and explores how these athletes encountered, experienced, and challenged the myth of Canadian racial refuge.

For more of Cameron’s work on sport history, see his article: