Over the past couple of weeks, the last of the spotted salamander larvae around Ithaca have left their eggs and are now swimming around in vernal pools, pools that form in the spring and dry up later in the year. They will feed and grow in these pools until they become adult salamanders and adopt a terrestrial lifestyle. To the larvae, their lives have just begun, but to an outside viewer, a lot has already happened.

Back in April, Jonah Marion (’20) wrote a blog post about the spotted salamander migration in Ithaca, which occurred on May 29. In the rain and under the cover of darkness, the salamanders had migrated from their forest habitat to the vernal pools where they reproduce. The salamander migration is just the beginning of a fascinating life history. With camera in hand, I have been continually checking up on the spotted salamanders and their embryonic offspring throughout the season.

Breeding

The spotted salamander breeds in vernal pools which are free of predatory fish since they dry up later in the year. Because adult salamanders are normally terrestrial, they have lungs, not gills. Thus, during breeding, they have to return to the surface of the water every few minutes to breathe. Despite being terrestrial most of the year, the salamanders are well adapted to swimming; with the help of their muscular tails, they can propel themselves through the water by moving in an S-shaped pattern.

During breeding itself, the males deposit sperm-filled spermatophores, which females pick up and store in their spermathecae. The spermathecae are organs used to store sperm for later use, sometimes even for future breeding seasons.1 When the females are ready, they will use their stored sperm to fertilize their eggs, and then deposit them onto sturdy pieces of vegetation.

After breeding, the adult salamanders return to land to continue their terrestrial lifestyle. The migration from their vernal pools doesn’t occur as simultaneously as the migration into their vernal pools; males can leave earlier than females since they don’t have to lay eggs, and individuals don’t all necessarily leave at the same time.

The Eggs

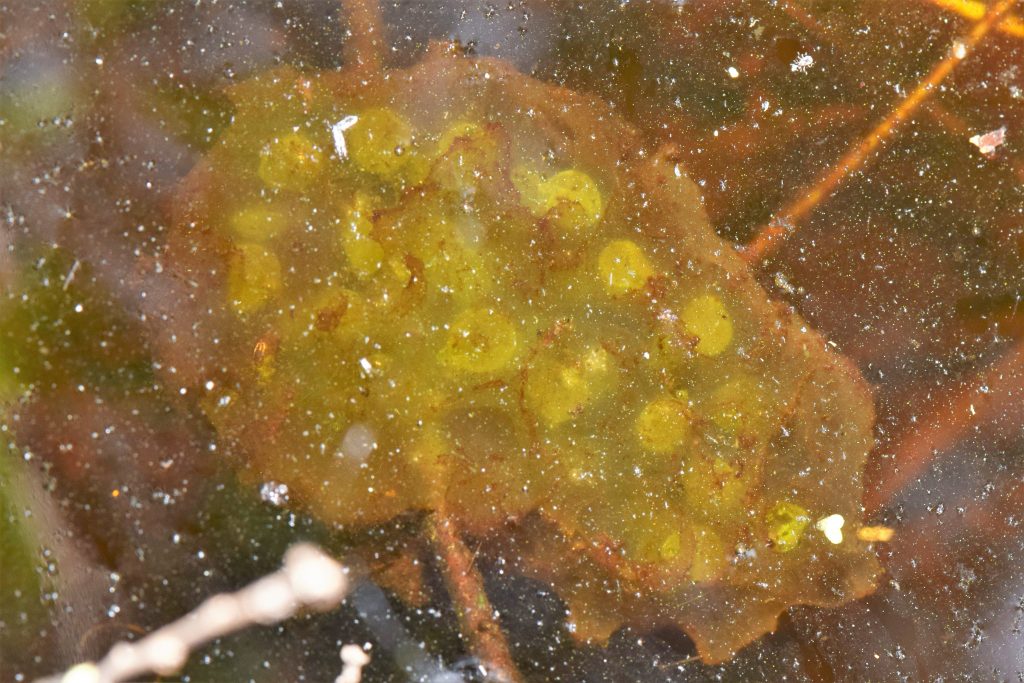

A spotted salamander egg mass secured to a branch in a vernal pool. The eggs are collectively surrounded by a thick protective jelly.

Spotted Salamander egg masses are wrapped around sturdy objects such the living branches of woody plants. The individual eggs are all packed within an outer gelatinous coat that protects them from predation. However, this thick coat makes it difficult for oxygen to diffuse to the developing embryos. To solve this problem, spotted salamanders have developed a symbiotic relationship with a type of green algae, Oophila amblystomatis. The algae grows within the individual eggs, producing oxygen through photosynthesis while acquiring nutrients from the embryonic waste products.2,3 More recent research has shown that these algae invade the embryonic salamander cells themselves and then disappear during later stages of development.4 This represents a unique case of endosymbiosis between a vertebrate and an alga which is still the subject of active research.5

~Five week old embryos. The eggs can be seen filled with symbiotic green algae.

A diving beetle larva standing on top of a mature egg mass. The thick outer jelly protects the salamander embryos from this predator.

The Larvae

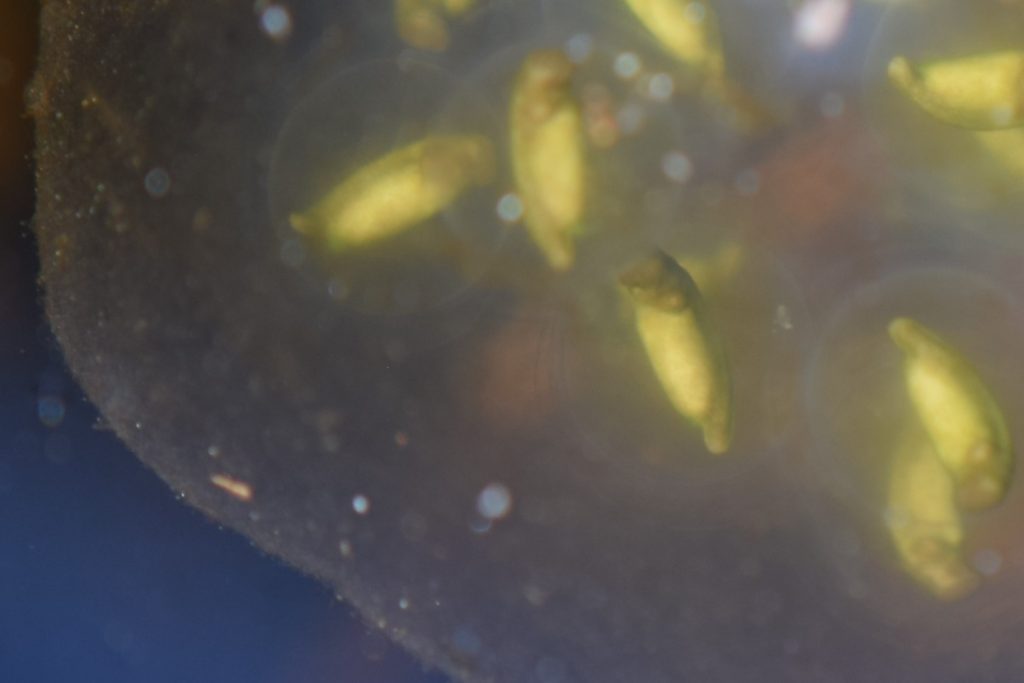

Two larvae, days before hatching. You can make out their eyes and the black spots of pigment covering their skin. Some of their nest-mates have already left.

The pace of embryonic development can vary between populations and between egg masses; usually it takes 4 to 7 weeks for the larvae to finally leave their eggs. For the Ithaca population it took about 7 weeks, with some variation between and even within egg masses.

When I checked on the egg masses in late May some of them were completely empty, with the eggs inside broken open. This was a sure sign that the larvae had outgrown their eggs and had taken refuge among the abundant leaf litter. Larval salamanders are adapted to life in their vernal pools; they have external gills and no legs. They will feed and grow in these pools for 2 to 4 months until they metamorphosize into adult terrestrial salamanders. Then, they will move onto land to seek permanent shelter in the forest. It may take 2 to 3 years before they become sexually mature, and the cycle can start all over again.

References

- Chandler, C. H., and K. R. Zamudio. “Reproductive success by large, closely related males facilitated by sperm storage in an aggregate breeding amphibian.” Molecular Ecology 17.6 (2008): 1564-1576.

- Bachmann, Marilyn D., et al. “Symbiosis between salamander eggs and green algae: microelectrode measurements inside eggs demonstrate effect of photosynthesis on oxygen concentration.” Canadian Journal of Zoology 64.7 (1986): 1586-1588.

- Pinder, A., and S. Friet. “Oxygen transport in egg masses of the amphibians Rana sylvatica and Ambystoma maculatum: convection, diffusion and oxygen production by algae.” Journal of Experimental Biology 197.1 (1994): 17-30.

- Kerney, Ryan, et al. “Intracellular invasion of green algae in a salamander host.” Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences 108.16 (2011): 6497-6502.

- Kerney, Ryan, John Burns, and Eunsoo KIM. “Investigating Mechanisms of Algal Entry into Salamander Cells.” Algal and cyanobacteria symbioses. 2017. 209-239.