Brian Caldwell, Chris Pelzer, and Matthew Ryan

Soil and Crop Sciences Section, School of Integrative Plant Science, Cornell University

Early in 2016, the Cornell Sustainable Cropping Systems Lab met with Bob Gelser, CEO of the Once Again Nut Butter Collective, Inc. (OANB) about the feasibility of growing organic confectionary sunflowers in New York State. OANB is an employee-owned business in Nunda, NY that produces several types of nut and seed butters and other products. The company makes organic sunflower butter, but imports organic sunflower seed kernels from Eastern Europe since local, organic supply sources are currently unable to meet OANB demand. Sunflower butter currently is a popular alternative to peanut and tree nut butters that have greater allergenic potential. Mr. Gelser proposed that our lab trial organic sunflowers, to gather experience and data under NYS conditions.

In general, there are two types of sunflower markets: oilseed and confectionary. Oilseed has greater oil content and is used in the production of vegetable oil, biodiesel, birdseed, and livestock feed. Confectionary has larger-sized seeds that are eaten as snacks or dehulled for food-grade kernel markets, including sunflower butter production. Smaller-sized confectionary seeds that do not make food-grade standards are often used for birdseed. Varieties suitable for both the oilseed and confectionary markets are called “conoil”.

While most US sunflower production is in the Western Plains and Northern Great Plains, sunflowers have the potential to broaden and diversify crop rotations in NYS. In the most recent census, USDA-NASS reports that in 2012 NYS produced 640,000 lb of sunflowers and 50,000 lb were confectionary sunflowers. Diversified rotations may help with weed management, break pest cycles, and increase farm viability.

With shared interests of increasing available crop markets and diversifying crop rotations for NYS organic farmers, we started an OANB-funded research project. Since we had no experience with the crop, we designed a simple experiment (Fig. 1). We acquired two varieties, Badger DMR (downy mildew-resistant) and N5LM307, an advanced new selection, donated by the major sunflower breeder Nuseed. They are both conoil types, suitable for dehulling. The trial was relatively large, about 2 acres, and our goal was to produce at least 700 lb of kernels of each variety. This is the amount OANB needed for roasting to evaluate the quality of the seeds for sunflower butter.

Growing sunflowers is very compatible with equipment that farmers use to grow corn grain. The seedbed was prepared by moldboard plowing and disking. Kreher’s 5-4-3 pelletized composted poultry manure was spread at 2000 lb/A and incorporated with a roller harrow. We used a 4-row JD 7200 MaxEmerge planter with finger pickup corn seed meters with 30 inch row spacing. The Kreher’s product was also applied through the corn planter at a rate of 220 lb/A, to give a total preplant plus starter nitrogen application of 111 lb N/A. We estimate that about half of that was available to the sunflower crop. Seeds of the two varieties were planted on June 10, 2016 at Musgrave Research Farm in Aurora, NY, at two target rates, 25,000 and 35,000/A, in a randomized complete block design.

The planting was done in the midst of a severe dry spell. Only 2.00 inches of rain had fallen in the month of May at Musgrave Farm, and 0.74 inches fell in June. The first significant rainfall after planting was 0.69 inches on July 19. Nonetheless, the sunflowers emerged well, though a bit slowly. By July 1, they were big enough to cultivate, which we did with a 2-row belly-mounted cultivator that we typically use for research plots. Sunflowers are an ideal crop to mechanically cultivate because they quickly reach a height of 4-5 inches. Soil can be lightly hilled around the base of the plants to smother weeds. Because of the dry conditions, weed emergence was also low. The rows were cultivated a second and last time with a JD 4-row row crop cultivator on July 11.

Sunflowers are quite drought-tolerant. They grew well through the drought and started flowering around August 15 at a height of 4-5 feet (Fig. 1).

On October 7, sunflowers were deemed physiologically mature evidenced by the banana-yellow color of the back of the sunflower disc. On this date, we hand-harvested sunflower heads for moisture content and yields. Plant population data and weed biomass samples were also collected. The Badger DMR seeds had a moisture content of 13.4% and the N5LM307, 15.7% at that time. However, the discs of the heads were still quite moist, around 80%. We did the hand harvest to measure the maximum potential yield of the crop. It is likely that a fair amount of moist material would have been mixed with the seed if we harvested with the combine on that day, presenting the danger of molding during storage. Given the high moisture of the disc, we decided to delay machine harvest. We also anticipated significant losses to bird predation over the next few weeks.

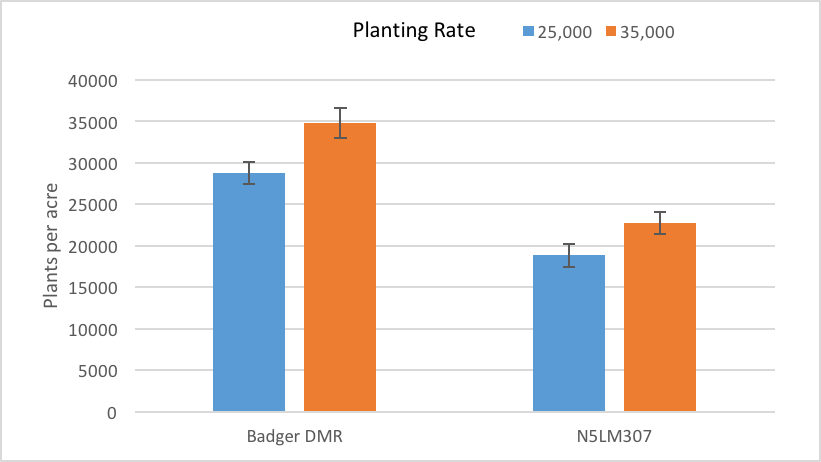

Plant stands were different, both by seeding rate and variety. Badger DMR established at significantly higher rates than the N5LM307 (Fig. 2).

Weed biomass was relatively low, though there were a few large plants that went to seed. This caused variability in the weed biomass data. Weed biomass was significantly different by variety but not by seeding rate. The Badger DMR variety had 48 lb/A of weed biomass, while N5LM307 had 202 lb/A. These low amounts of weed biomass likely did not significantly reduce yields.

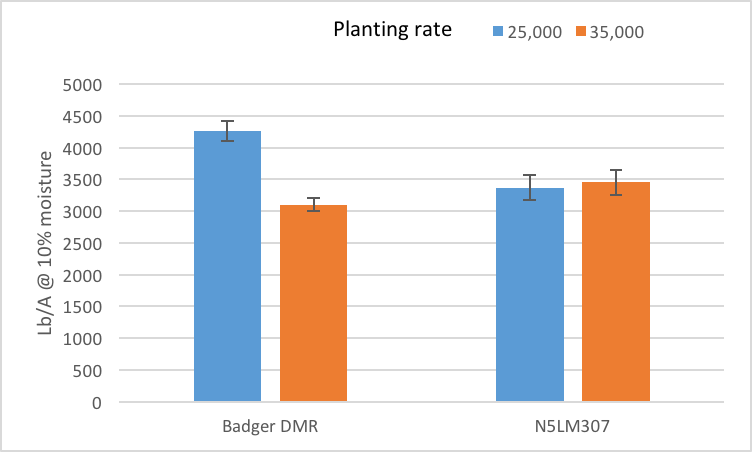

Hand harvest yields were high. The low seeding rate of Badger DMR yielded the most at 4260 lb/A (10% moisture). The high seeding rate of Badger and both rates of N5LM307 yielded the same at 3100-3450 lb/A (Fig. 3). The low rate of Badger DMR may have performed better due to lower within-crop competition during the dry conditions. These yields are considerably higher than the 1000-1400 lb/A reported for dryland production in Texas. However, it should be kept in mind that this was the first year for sunflowers at the Musgrave Research Farm, and thus pest and disease populations have not built up.

When we harvested with the combine on November 1, our bulk measurements showed average yields of 3300 lb/A for Badger DMR and 3600 for N5LM307 (Fig. 4). Evidently, there was not much loss to birds. The combine handled the crop well, leaving little trash in the harvested crop. The only modification we made to the standard corn head was to install Golden Plains sunflower plates, which direct the sunflower heads in and prevent seed loss out the front (Fig. 5). These cost $1142 used or $1693 new for our Case IH 1644 4-row combine and were easily installed. We immediately put the harvested seed into 1-ton bulk tote bags and installed a screw-in aerator in each (Fig. 6). This small-scale approach seemed to do a very good job of removing excess moisture and kept the seeds from heating up. Drying temperatures need to be held below 110 degrees F to maintain quality. After 4 days, they had dried down to the 8-9% range, which is considered ideal for storage, so we turned off the aerators.

Two more steps remain before they can be processed into sunflower butter. First, they will be cleaned of crop residue, and then dehulled. The seeds were delivered to OANB and they will be in charge of these steps, which we will document. Finally, OANB will process them into sunflower butter and evaluate the quality of the product.

Hulled organic sunflower seeds may typically receive a delivered price of $0.90-$1.10/lb. Estimates vary, but the seeds are reported to be about 60-80% kernel. Whole seed yields of 3000 lb/A would produce dehulled yields of about 1800+ lb/A, minus losses during dehulling. The gross returns from such a sunflower crop would be good, but we do not have data on the costs and losses from the dehulling operation. Drying after harvest is critical and may add to costs. Otherwise, growing and harvest costs appear similar to organic corn. More work will be needed in the future to determine yield variability and cost numbers.

The dry season of 2016 was perhaps ideal for sunflowers in some ways. First, they appear to have a good competitive advantage against weeds under dry conditions. Second, dry weather minimizes the occurrence of white mold, Sclerotinia sclerotiorum, which can affect all parts of the plant. It can also infect soybeans and reduce yields and quality of this valuable crop. We did not see white mold in 2016.

Sunflowers can perform well and mature even if planted in early- to mid-June, making them a valuable option when wet soil conditions delay planting outside of the optimum corn and soybean window. They also do not need high fertility levels and provide diversity within the rotation, with the important caveat of being a host for white mold. Our 2016 agronomic results were favorable. Later this winter, we will also find out processing results from OANB for these varieties. We need to determine the performance of sunflowers in wetter growing seasons. Other factors we hope to examine in the future are whether they will tend to increase white mold on soybeans within the rotation, and whether sunflower pests (including birds) and diseases will increase.

This project was undertaken with the generous support of the Once Again Nut Butter Collective, Inc., Nunda, NY. Seed was provided by Nuseed US, Alsip, IL.