Winter has arrived! While there isn’t much to be doing outside in our gardens, the winter is a great opportunity to spend time learning more about gardening. So grab one of these books recommended by our Master Gardener Volunteers, sit by the fire, and spend time cultivating your mind this winter.

Winter has arrived! While there isn’t much to be doing outside in our gardens, the winter is a great opportunity to spend time learning more about gardening. So grab one of these books recommended by our Master Gardener Volunteers, sit by the fire, and spend time cultivating your mind this winter.

Book List

Freedom’s Gardener: James F. Brown, Horticulture, and the Hudson Valley in Antebellum America by Myra Beth Young Armstead

Garden Alchemy: 80 Recipes and Concoctions for Organic Fertilizers, Plant Elixirs, Potting Mixes, Pest Deterrents, and More by Stephanie Rose

Good Garden Bugs by Mary M. Gardiner, Ph. D.

The Know Maintenance Perennial Garden by Roy Diblik

Natural Companions: The Garden Lover’s Guide to Plant Combinations by Ken Druse

Square Foot Gardening with Kids by Mel Bartholomew

The Week-by-Week Vegetable Gardner’s Handbook by Ron and Jennifer Kujawski

The Weekend Homesteader: A Twelve Month Guide to Self-Sufficiency by Anna Hess

The Well-Gardened Mind: The Restorative Power of Nature by Sue Stuart-Smith

A Year at Brandywine Cottage by David L. Culp

Your Wellbeing Garden: How to Make Your Garden Good for You – Science, Design, Function by D.K. Publishing

Freedom’s Gardener: James F. Brown, Horticulture, and the Hudson Valley in Antebellum America

Freedom’s Gardener: James F. Brown, Horticulture, and the Hudson Valley in Antebellum America

by Myra Beth Young Armstead

Reviewed by Madelene Knaggs, New Windsor Master Gardener Volunteer

Freedom’s Gardener is impeccably researched and full of detail. It is the kind of book that grabs the attention of readers interested in gardening, local history, Black history, and the concept of freedom. Armstead, a professor of history at Bard College, extracts small details from the diary of James F. Brown to compose a story illustrating the concept of freedom as it developed in the United States in the decades following the Revolutionary War.

James F. Brown was born a slave in 1793 and died a free man in 1868. He escaped slavery in Maryland to the Hudson Valley of New York State, where he was employed as a gardener by the wealthy Verplanck family in Beacon, NY (on what is presently the Mount Gulian Historic Site).

Brown kept a detailed diary over 39 years, with entries covering weather, gardening, and steamboat schedules, as well as domestic matters. James began his career with the Verplancks as a waiter and a laborer, but eventually assumed the duties as the Verplanck Estate’s master gardener. He managed and supervised garden, farm, and nursery workers. He was also responsible for making major purchases for the Verplanck house and garden. He frequently interacted in Newburgh with Andrew Jackson Downing, the famed lAmerican landscape designer and editor of The Horticulturist magazine (1846–1852). Brown attended the Pennsylvania Horticultural Society Show in Philadelphia as well as the New York Horticultural Society Exhibition.

This book has been recommended by the Library Journal to historians of antebellum America and the social aspects of horticulture, as well as those interested in historical diaries. Armstead’s well-researched study of Brown’s work greatly expands our understanding of the Hudson Valley and the people and plants that have shaped it.

Garden Alchemy: 80 Recipes and Concoctions for Organic Fertilizers, Plant Elixirs, Potting Mixes, Pest Deterrents, and More

Garden Alchemy: 80 Recipes and Concoctions for Organic Fertilizers, Plant Elixirs, Potting Mixes, Pest Deterrents, and More

by Stephanie Rose

Reviewed by Mary Presutti, New Windsor Master Gardener Volunteer

As a newly minted Master Gardener Volunteer, I frequently turn to my class notes for advice in the garden. Now I have another, more portable source. In this one handy, slim volume, Canadian Master Gardener Stephanie Rose has compiled a nifty hands-on guide with useful recipes to get everyone’s garden in top shape.

The book is loaded with step-by-step instructions beginning with homemade methods to test your soil, then on to recipes for soil amendment, custom mulch, compost boosters, fertilizers, garden teas, potting soils, and even a method to produce your own worm castings. The ingredients are common items available in your home.

Even wildlife has not been left out. There are techniques for encouraging as well as discouraging nature in the garden. Some of my plants go outdoors in the summer months. They invariably bring fungus gnats back indoors in the fall. She has a fix to keep them away. She also includes a bottle trap for flies, wasps, and stinkbugs—all with their own individual bait recipes.

As a plus, Ms. Rose has included some fun activities to keep gardeners occupied while their plants are sleeping this winter season. You can make seed bombs, suet holders, butterfly puddlers, and more.

Garden Alchemy is chock full of beautiful, interesting photographs and diagrams that complement the easy to understand, straight to the point text. I recommend it for all gardeners.

Good Garden Bugs

Good Garden Bugs

by Mary M. Gardiner, Ph.D.

Review by Donna Beyer, New Windsor Master Gardener Volunteer

All gardeners must deal with bugs — good bugs, bad bugs — but some of us aren’t sure which is which. Good Garden Bugs is directed to the home gardener who might not know the difference. As gardeners, we invest time and effort into making our gardens the most beautiful and productive they can be, yet bugs can present challenges to our efforts. Most of us understand the need for good bugs, but sometimes find it difficult to live in harmony with them.

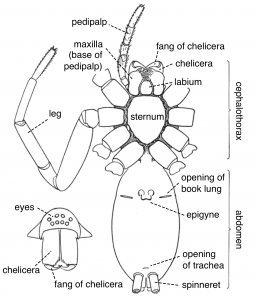

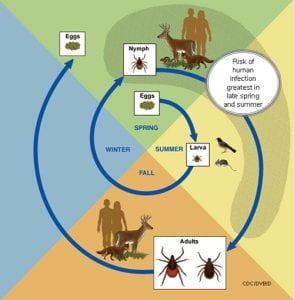

The book begins by providing information on the classification, anatomy, and the life cycle of garden bugs. The information helps the gardener understand how each stage of a bug’s development has different enemies and threats, and is presented in a way that non-academics can understand. How bugs overwinter and mature provides the gardener with valuable insight into promoting good garden bugs.

The chapter that discusses controls we use to regulate bug populations can help gardeners understand how their actions affect them. This section also stresses the need for native plants to promote healthy habitats that support good bug populations.

The chapters that follow are the core of the book. Each subsequent chapter is dedicated to an order of bug that describes the unique attributes and common examples of bugs that fall into that order. The book also includes large color photos with descriptions of each.

Over half the chapters are dedicated to wasps, beetles, and spiders. These bugs are the most plentiful and can be difficult to identify. These orders can do serious damage to plants and humans alike, so being able to identify these “good” bugs is especially important. Gardeners want to promote good bugs that fall into these orders, but also want to protect themselves and their gardens.

Currently, in the age of the internet, having a resource you can carry to the garden that will assist with pest identification is invaluable. This book is slim but does not skimp on content and is a valuable addition to a home gardener’s library.

The Know Maintenance Perennial Garden

The Know Maintenance Perennial Garden

by Roy Diblik

Reviewed by Cecille Jones, Monroe Master Gardener Volunteer

If the title of this book doesn’t hook you, perhaps the words on the cover will. In red ink, it loudly declares knowing your plants means less work. Or perhaps you’ve heard of Roy Diblik, the renowned plantsman behind the Lurie Garden at Millennium Park in Chicago.

Diblik’s approach to gardening stresses harmony with how plants grow and interact with each other. He advocates knowing your plants so you can plant them in self-sustaining communities. By doing so, you will spend less time maintaining them and more time enjoying them.

The author focuses on perennials because he believes they are the foundation of durable, diverse and beautiful gardens. According to Diblik, once you’re familiar with perennials, then you will recognize how and when to add annuals, vegetables, herbs, shrubs and trees.

Diblik believes that traditional gardening has become so culturally defined over the last 50 years that it is now a source of frustration and defeat for most gardeners.

In the first four chapters, he covers the basics – from understanding plant growth to soil, light, site preparation, and more. Chapter 5 covers 74 key perennials selected for their dependability, suitability to the northern half of the U.S., adaptability to soil & seasonal changes, and durability.

The true treasure is saved for Chapter 6 and beyond, where Diblik provides more than 60 garden plans, each designed to cover a 10 – 14’ rectangle, categorized by plans for growing in sun or shade, and complete with notes on care and maintenance. Assuming you are diligent about care and maintenance, Diblik claims that each plan should take about 3 to 4 hours of work per week.

Diblik’s approach will put you on a path to a style of gardening that stresses harmony, simplicity and enjoyment.

Natural Companions: The Garden Lover’s Guide to Plant Combinations

Natural Companions: The Garden Lover’s Guide to Plant Combinations

by Ken Druse

Reviewed by Gerda Krogslund, Middletown Senior Master Gardener Volunteer

For this book, author Ken Druse worked in conjunction with artist Ellen Hoverkamp who provided the beautiful botanical photographs throughout. Each chapter explores plants in a different light looking at season, family, form, function, color, spirit of place, or theme.

Take a journey through the seasons starting with signs of spring and continuing through the year concluding with winter and new awakenings. Learn about different plant families and delve into the numerous varieties found in each. Form follows function – examine the many different shapes, textures, structures and growth habit of flowers and other plants. Be inspired by pictures of flowers with both similar colors and exciting color combinations. Consider the spirit of place and think about what you can plant in woodlands, meadows, wetlands, rain gardens, and rock gardens. Explore themed gardens grown for fragrance, roses, pollinators, birds, cutting, edible plants, herbs, medicinal plants, and toxic plants.

This is not a “how-to” manual but a book that suggests possible plant combinations for your consideration. It gives you lots of ideas in which you can take your reliable basic plants and add others to make your garden even more spectacular. Ken Druse knows that gardening is very personable and suggests that while you read through the book, you make lists of combinations that appeal to you.

A garden is never really complete but more a work in progress as we continually experiment with new plants and new plant arrangements. I’ve spent hours going through this book and I know I’ll come back again and again.

Square Foot Gardening with Kids

Square Foot Gardening with Kids

by Mel Bartholomew

Reviewed by Brooke Moore, New Windsor Master Gardener Volunteer

Getting children interested in growing food and learning more about the natural world is an admirable goal. And one that does not have to be boring or pedantic.

This lovely book by the master of Square Foot Gardening, provides kids from toddlers to teens with all the tools they need to build, manage, grow and harvest a vegetable garden. It encourages starting small and building more as confidence and experience lead one to wanting a larger planting area.

With a format that provides age-appropriate tasks and goals at every step, this book also works for the whole family. I loved that there are clues to help parents not be overly involved but rather encourage the children to figure out how to do things themselves. It covers building raised beds, making soil mixes, how to make a grid system, water issues, protecting plants from predators, best growing practices, and much more.

Teachers and classroom projects are also a part of the book, and these can be used by anyone. Math, science, art, and history are all related to gardening, and the book provides simple and interesting activities to bring these skills into the garden and to use the garden to develop entirely new ones. Measuring, weighing, keeping a planting journal are all well described and encouraged. There are good photos and illustrations for each step and lots of handy tips and “how to” suggestions.

This is a book with “kids” in the title, but it truly is a book for anyone and everyone interested in exploring how to use this simple system to have a successful garden harvest.

The Week-by-Week Vegetable Gardner’s Handbook

The Week-by-Week Vegetable Gardner’s Handbook

by Ron and Jennifer Kujawski

Reviewed by Kimberly Marshall, Washingtonville Master Gardener Volunteer

If there were only one vegetable gardening book I could use throughout the gardening year, it would be The Week-by-Week Vegetable Gardener’s Handbook by Ron and Jennifer Kujawski. This dynamic father-and-daughter gardening duo have made an indispensable resource that should grace the bookshelves of vegetable gardeners everywhere.

It provides week-by-week vegetable gardening how-to’s that coincide with each planting season. A chart at the beginning of the book helps you identify where you are in your own area’s growing season, using your first and last frost dates as a guide. For example, if your last frost date is mid-May, as it is for many of us here in Orange County, you enter that date in the calendar’s “Week 1,” which starts your weekly to-do’s (first week, two weeks out, three weeks out, etc.).

Based on these dates, the book explains which week to start seeds indoors, plant cover crops, look for pests, harvest your crops, and fertilize each and every vegetable you can think of, with plenty of gardening tips and tricks along the way. There are even steps for gardening in the winter, with instructions for planning gardens and ordering seeds, so you can work on or think about your garden all year long.

The book also includes space for journaling your thoughts and experiences. There is ample room for notes in each section to remind yourself of what you planted and any issues you might have experienced, helping you to avoid making the same mistakes the following year.

If you’re looking for a step-by-step vegetable gardening book that tells you exactly what to do and when to do it, give this one a try—especially if you find the idea of vegetable gardening a bit overwhelming, like I do. It breaks everything down into easy steps, making even the scariest parts of gardening seem effortless while helping you realize what’s truly possible for your garden along the way.

The Weekend Homesteader: A Twelve Month Guide to Self-Sufficiency

The Weekend Homesteader: A Twelve Month Guide to Self-Sufficiency

by Anna Hess

Reviewed by Robin Portelli, Cornwall Master Gardener Volunteer

As I was perusing through gardening books on the Libby App from my local library, the book title, The Weekend Homesteader: A Twelve-Month Guide to Self Sufficiency by Anna Hess caught my attention. I was envisioning a book with information that would inspire me to become a self-sufficient gardener without feeling overwhelmed or pressured that I needed to go off the grid or never buy grocery produce again. I was not disappointed.

In her introduction, Anna Hess immediately connects with the novice homesteader. She understands that the dream of full-time homesteading can be daunting for most people. “Weekend Homesteader is full of short projects that you can use to dip your toes into the vast ocean of homesteading without becoming overwhelmed,” she writes. So, I began to read.

The book is divided by months beginning in the month of April or October if you live down under. Each month introduces you to topics that are important factors in growing a successful garden and maintaining a small homestead. Some homesteading basics covered that are more familiar to most of us include budgeting skills and record keeping (ugh!), healthy soil, garden rotation, and how to build a chicken coop. Anna Hess also touches upon less well-known details and tips such as how to find space to plant if you live in the city, how to stay warm without electricity for longer periods of time, and how to extend the gardening season by making your own garden hoops. Recipes, canning, cooking, and details of food/seed storing options are among some of the other multitude of topics.

Overall, I would give this book 4.5/5 stars.

Pros: It was well organized and gave many tips that only an experienced homesteader would know. It could help a novice homesteader avoid rookie mistakes. This book was published in 2012, but the topics and information are still very practical and relevant.

Cons: It covers the basics so an already experienced homesteader may not reap much benefit by reading it. Also, it is missing a chapter specific to urban gardening topics.

The Well-Gardened Mind: The Restorative Power of Nature

The Well-Gardened Mind: The Restorative Power of Nature

by Sue Stuart-Smith

Reviewed by Sharon Lunden, Goshen Master Gardener Volunteer

In The Well-Gardened Mind, Stuart-Smith, a British psychiatrist and psychotherapist, delves into the therapeutic aspects of immersing yourself in a garden. This is not a how-to garden book but instead outlines the well-researched benefits to the human body, mind, and soul to be found in the natural world around us.

Our brain cells are like branching trees, requiring pruning, weeding, and room to grow. Experience and pain can be “composted” into something beneficial. Gardens reflect our lives, periods of yield and beauty, loss and rest. Our minds as gardens seek light, cultivation, seeding, nourishment, watering, and replenishment. Souls and bodies begin to heal and thrive in the peace, safety, and beauty of the confines of a flower or vegetable garden. We need the earth as much as the earth needs us to care for and cherish it, a full circle. By learning to care for a garden, we better learn to care for ourselves and others.

This is a fascinating book which I recommend to you, as it can prove helpful and comforting in the midst of the stress of these difficult times.

If we put energy into cultivating the earth, we are given something back. There is magic in it and there is hard work in it, but the fruits and flowers of the earth are a form of goodness that is real; they are worth believing in and are not out of reach. When we sow a seed, we plant a narrative of future possibility. It is an action of hope. Not all the seeds we sow will germinate, but there is a sense of security that comes from knowing you have seeds in the ground. (pp. 65–66)

A Year at Brandywine Cottage

A Year at Brandywine Cottage

by David L. Culp

Reviewed by Madelene Knaggs, New Windsor Master Gardener Volunteer

A Year at Brandywine Cottage leads us on a journey through an exquisite garden that represents a lifetime of hard work, passion, successes and disappointments, experience and knowledge. Engaging prose and beautiful photography take the armchair gardener on a virtual tour through each season as the author informs us of the Latin genus and species and the botanical and historical facts about each plant.

Author and gardener David Culp states, “By looking closely at my garden over a period of time, and allowing it to speak to me, I find that the garden at Brandywine Cottage wants six seasons. As you will see, this book chronicles what happens in my garden over the course of those seasons.”

Culp demonstrates his deep knowledge of plants season by season with such tips and techniques for a successful layered garden as adding pots of tropicals (he has 400 pots) into the beds to boost a tired August garden, or clipping distracting dead leaves off hellebores before they bloom. He also weaves in family and local recipes using ingredients from his own beautiful vegetable garden.

Beginning in February (in the chapter “Early Spring”), he shows us the sleepy phase in the garden when most people are oblivious to any plant life. He proves that there is much to behold—the emerging bulbs of crocus, dwarf iris, glory-of-the-snow, winter aconite, witch hazels, and the author’s large collection of snowdrops. As the season progresses into March, daffodils and hellebores take center stage. He continues to show the progression and overlapping from season to season and from outdoors to inside the home.

This book will inspire readers with ideas for their own gardens, and will encourage plans in anticipation of the upcoming season.

Your Wellbeing Garden: How to Make Your Garden Good for You – Science, Design, Function

Your Wellbeing Garden: How to Make Your Garden Good for You – Science, Design, Function

by D.K. Publishing

Review by Patricia Henighan, Walden Master Gardener Volunteer

If you have been gardening for a while, you probably don’t need to be convinced that your garden is good for you. Nevertheless, this delightfully designed and easy to digest book uses scientific research drawn together by a team of scientists from the Royal Horticultural Society to present the whys and hows of creating an outdoor space that nourishes both the mind and the body, and is good for the planet. Each section encapsulates the latest research on topics such as how to fight air pollution, reduce noise pollution, help pollinators, address climate change, and provide fodder for your brain.

The authors use diagrams and illustrations to explain concepts such as how different types of leaves trap air pollutants and why vegetation is a better at reducing noise pollution than a fence or a wall. They explore topics such as Ogren Plant Allergy Scale (OPALS) which rates plants from 1 to 10 for allergenicity using eye-catching illustrations that show why certain flower and tree species are better choices if you are looking to avoid flying pollen.

Many people spend time outside to find peace and tranquility in a chaotic world. Research has found that when seeking “natural restoration”, we respond best to natural features that are moderately complex – not too smooth and not too busy. A grassy area with openings and some trees provides the highest rewards for inducing tranquility. Fractals or repeating branching patterns, which occur frequently in nature, can be added to a garden to ensure the landscape provides release for the brain from stress and anxiety. The authors encourage you to design a mindfulness corner with a comfortable seat in an area cushioned from street noise with a soothing sound of water or bees buzzing. Who said gardens must be all work?

Gardening can be a solitary pursuit or a communal activity. It can benefit people from all walks of life. Children and adults with special needs can benefit from the experience of growing flowers and food crops. Horticultural therapy is a way in which gardening is used to help people suffering from trauma and illness. For immigrants, growing crops from their home country can help to allay homesickness. And when it comes to children and gardening, psychologists have found that children can cultivate character by taking care of their own individual garden plots. It is also thought that by handling dirt at an early age, children increase their exposure to beneficial microbes, which may boost the immune system.

Since climate change is an ongoing challenge for everyone, the last section covers many aspects of creating a sustainable garden. There are suggestions on how to change barren, water-gobbling lawns into more resilient spaces and the latest recommendations on how to care for your soil, avoid impermeable surfaces, capture run-off, and design rain gardens. Obviously, it is a win-win situation as making your garden better for you will also make it better for the environment.

It is believed that the Christmas tree originated in Latvia in the early 1500s and the tradition was brought to the United States by German settlers in the 1800s. It was originally tabletop size but soon became floor to ceiling size. Christmas trees started to be sold commercially in the United States in 1851. At that time, Christmas trees were harvested from forests. Eventually conservationists became concerned that the natural supply of evergreens was being decimated, which lead to the creation of Christmas Tree Farms. The first Christmas Tree Farm in the United States was started in New Jersey in 1901 and grew Norway spruce trees.

It is believed that the Christmas tree originated in Latvia in the early 1500s and the tradition was brought to the United States by German settlers in the 1800s. It was originally tabletop size but soon became floor to ceiling size. Christmas trees started to be sold commercially in the United States in 1851. At that time, Christmas trees were harvested from forests. Eventually conservationists became concerned that the natural supply of evergreens was being decimated, which lead to the creation of Christmas Tree Farms. The first Christmas Tree Farm in the United States was started in New Jersey in 1901 and grew Norway spruce trees. The eastern white pine is a very large tree, fifty to eighty feet tall and twenty to forty feet wide. It can often be identified by its lone silhouette as it towers over other trees in the forest or by its wide base and gradual layering of upswept branches up to the top.

The eastern white pine is a very large tree, fifty to eighty feet tall and twenty to forty feet wide. It can often be identified by its lone silhouette as it towers over other trees in the forest or by its wide base and gradual layering of upswept branches up to the top.  Somewhere between 25-35 million live Christmas trees are sold in the United States each year. When grown as a Christmas tree, the eastern white pine is cut at six feet and is usually sheared. It takes 6-8 years to produce an eastern white pine Christmas tree whereas it takes other an average 15 years for other Christmas tree species making it very profitable for Christmas tree growers.

Somewhere between 25-35 million live Christmas trees are sold in the United States each year. When grown as a Christmas tree, the eastern white pine is cut at six feet and is usually sheared. It takes 6-8 years to produce an eastern white pine Christmas tree whereas it takes other an average 15 years for other Christmas tree species making it very profitable for Christmas tree growers.

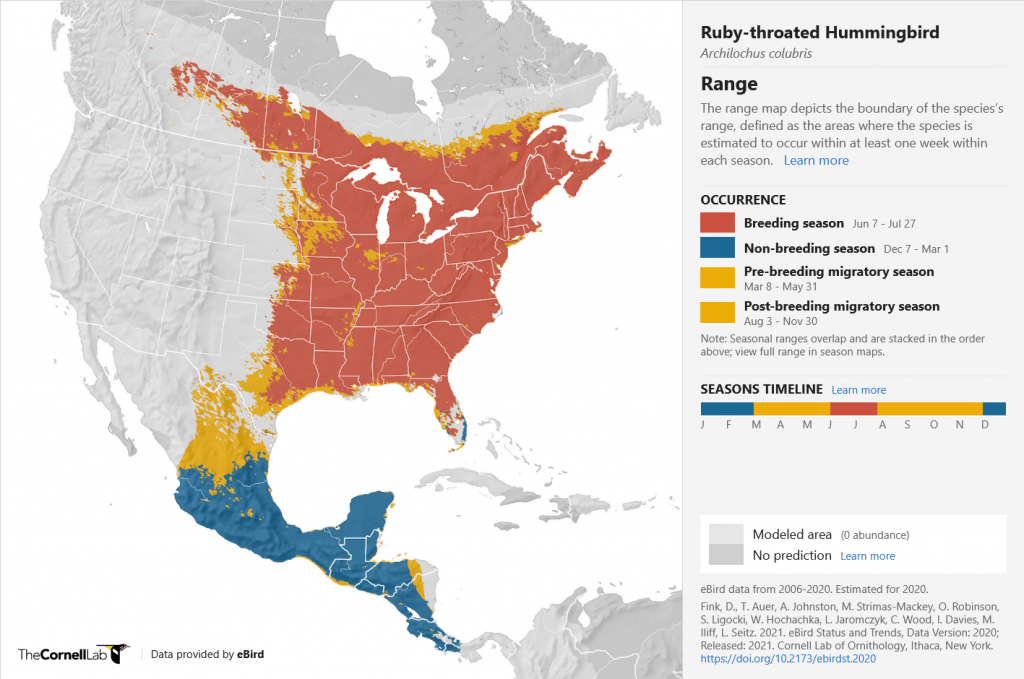

Once she reached the Gulf, there was a final push across the water as she flew nonstop for 500 miles until she reached land. Young and older birds may fly along the coastline into Mexico to reach their destination. My bird may have had the good fortune to alight on a passing boat or possibly an oil rig for a short rest. It is an amazing journey for such a tiny bird.

Once she reached the Gulf, there was a final push across the water as she flew nonstop for 500 miles until she reached land. Young and older birds may fly along the coastline into Mexico to reach their destination. My bird may have had the good fortune to alight on a passing boat or possibly an oil rig for a short rest. It is an amazing journey for such a tiny bird.

One Size Fits All Gloves! Do not buy someone else gloves, unless you can get an exact match to the pair that the gardener currently wears every single time they are out toiling in their garden. Next to shoes gloves really need to fit and feel properly for them to work. Too big and you have no control over your fingers, too small and they are painful, too thin and the dirt and thorns go right through, too thick and you don’t have enough dexterity. Stay away from gloves.

One Size Fits All Gloves! Do not buy someone else gloves, unless you can get an exact match to the pair that the gardener currently wears every single time they are out toiling in their garden. Next to shoes gloves really need to fit and feel properly for them to work. Too big and you have no control over your fingers, too small and they are painful, too thin and the dirt and thorns go right through, too thick and you don’t have enough dexterity. Stay away from gloves. House plants. Between the plants that were brought in to overwinter and the cuttings that are taking up all the spare room on the window ledges, even the most dedicated gardener probably has more than enough house plants by mid-winter. If you absolutely, positively know that there is a plant your favorite gardener is lusting after then okay, you can give it to them. Otherwise, just look and enjoy them at the store.

House plants. Between the plants that were brought in to overwinter and the cuttings that are taking up all the spare room on the window ledges, even the most dedicated gardener probably has more than enough house plants by mid-winter. If you absolutely, positively know that there is a plant your favorite gardener is lusting after then okay, you can give it to them. Otherwise, just look and enjoy them at the store. Pruners. Sort of like gloves everyone has their favorites and unless you have been given the exact one that is wanted a gift certificate is a way better option.

Pruners. Sort of like gloves everyone has their favorites and unless you have been given the exact one that is wanted a gift certificate is a way better option. Hoses. Another way personal item that is specific to the person who does the watering. Size, weight, length, and material make a huge difference. Common complaints from those of us who do the watering include it’s too heavy to drag with water in it, it kinks to easily and shorts out the flow, it is impossible to reel up and store making an annoying task even more so. If you have a ‘Gift List’ with a specific hose listed then perfect, get that one but do NOT purchase a substitute.

Hoses. Another way personal item that is specific to the person who does the watering. Size, weight, length, and material make a huge difference. Common complaints from those of us who do the watering include it’s too heavy to drag with water in it, it kinks to easily and shorts out the flow, it is impossible to reel up and store making an annoying task even more so. If you have a ‘Gift List’ with a specific hose listed then perfect, get that one but do NOT purchase a substitute. Garden Boots. (

Garden Boots. ( Spades or Shovels. Length of handle, weight, shape of the head, all are a very personal preferences. Again, if one specific one was asked for perfect. Otherwise offer to take them out shopping to pick their favorite!

Spades or Shovels. Length of handle, weight, shape of the head, all are a very personal preferences. Again, if one specific one was asked for perfect. Otherwise offer to take them out shopping to pick their favorite! Time. My number one suggestion is the gift of time, time in which you will help the gardener in you life dig holes, rake, mulch, move plants, visit a garden to get ideas, shop for a native plants, etc. Having a freely given chunk of time to help out will be a gift that can be given with love and received with excitement.

Time. My number one suggestion is the gift of time, time in which you will help the gardener in you life dig holes, rake, mulch, move plants, visit a garden to get ideas, shop for a native plants, etc. Having a freely given chunk of time to help out will be a gift that can be given with love and received with excitement.

Framed photo of last year’s bloom. Look through the photos on your phone and pick something that reminds you of the best of the garden. Put it in a pretty frame and it will make everyone smile through the winter months. Consider getting a metal print that does not need a frame. These are dramatic and really showcase a bloom! My favorite budget friendly but high-quality source is

Framed photo of last year’s bloom. Look through the photos on your phone and pick something that reminds you of the best of the garden. Put it in a pretty frame and it will make everyone smile through the winter months. Consider getting a metal print that does not need a frame. These are dramatic and really showcase a bloom! My favorite budget friendly but high-quality source is

One of the most recognizable symbols of fall is a branch of oak leaves and a couple of acorns. Oak trees (Quercus spp.) have been around for approximately 55 million years old, with the oldest North American specimen being 44 million years old. Long before pumpkins and corn stalks came to symbolize harvest and bounty, people depended on the humble acorn and majestic oak tree for sustenance and shelter. Today we think of oak trees in terms of shade, firewood, and sturdy furniture, but as acorns can be stored for long periods of time and the flour made from them is quite nutritious for thousands of years acorns were the main food staple for people in

One of the most recognizable symbols of fall is a branch of oak leaves and a couple of acorns. Oak trees (Quercus spp.) have been around for approximately 55 million years old, with the oldest North American specimen being 44 million years old. Long before pumpkins and corn stalks came to symbolize harvest and bounty, people depended on the humble acorn and majestic oak tree for sustenance and shelter. Today we think of oak trees in terms of shade, firewood, and sturdy furniture, but as acorns can be stored for long periods of time and the flour made from them is quite nutritious for thousands of years acorns were the main food staple for people in

When all environmental factors work together, oak trees can produce an overabundance of acorns in what scientists call a “

When all environmental factors work together, oak trees can produce an overabundance of acorns in what scientists call a “

This is a perfect time to get a start on weed management for the spring. Shorter days and colder weather in the months ahead will reduce the activity of plant growth. You want to keep the process as natural as possible. Pull weeds to your hearts content without overly disturbing the soil. Don’t use hoes or rakes, and don’t turn the soil over unless you must. When you disturb the soil too much seeds resting on top of soil get planted in the loose soil, and seeds deep in the soil are brought closer to the surface where they will be able to sprout. Every time you move soil around without a purpose, the roots and seeds of unwanted plants are given the go ahead to sprout away.

This is a perfect time to get a start on weed management for the spring. Shorter days and colder weather in the months ahead will reduce the activity of plant growth. You want to keep the process as natural as possible. Pull weeds to your hearts content without overly disturbing the soil. Don’t use hoes or rakes, and don’t turn the soil over unless you must. When you disturb the soil too much seeds resting on top of soil get planted in the loose soil, and seeds deep in the soil are brought closer to the surface where they will be able to sprout. Every time you move soil around without a purpose, the roots and seeds of unwanted plants are given the go ahead to sprout away. Bare soil is an invitation for weeds to… well, put down roots! Cover weeds that you want gone by the spring with a layer of weighted cardboard. Sometimes I think I shop online more for the cardboard shipping boxes then for what’s inside. I also love using sheets of bark from my fireplace wood in and around my garden plants. Tree bark adds nutrients, cuts down on weed growth, and is a good insulator for tender plants. Grass clippings or shredded leaves make a nice winter mulch, but cut up leaves soon after they fall to the ground before insects and small animals take shelter. Rake only the leaves you need to, leaving a goodly amount for insects to find winter cover.

Bare soil is an invitation for weeds to… well, put down roots! Cover weeds that you want gone by the spring with a layer of weighted cardboard. Sometimes I think I shop online more for the cardboard shipping boxes then for what’s inside. I also love using sheets of bark from my fireplace wood in and around my garden plants. Tree bark adds nutrients, cuts down on weed growth, and is a good insulator for tender plants. Grass clippings or shredded leaves make a nice winter mulch, but cut up leaves soon after they fall to the ground before insects and small animals take shelter. Rake only the leaves you need to, leaving a goodly amount for insects to find winter cover.

Spring flowering bulbs are usually classified by four basic characteristics: bloom time (early, mid, and late spring), height, bloom form, and color. Depending on your garden aesthetic, one or more of these characteristics will help determine what bulbs are right for you.

Spring flowering bulbs are usually classified by four basic characteristics: bloom time (early, mid, and late spring), height, bloom form, and color. Depending on your garden aesthetic, one or more of these characteristics will help determine what bulbs are right for you. Bulb growers offer mixes based on color, bloom time, and compatible forms. You can also create your own mix by ordering a selection of bulbs and mixing them together. Mixes are often an economical way to have both a variety, and a mix of more expensive bulbs and more common ones. If you have never had any bulbs this is a good way to get started and feel confident in your abilities to grow bulbs.

Bulb growers offer mixes based on color, bloom time, and compatible forms. You can also create your own mix by ordering a selection of bulbs and mixing them together. Mixes are often an economical way to have both a variety, and a mix of more expensive bulbs and more common ones. If you have never had any bulbs this is a good way to get started and feel confident in your abilities to grow bulbs.

Bulbs can be included as part of a cutting garden as well. Consider using a portion of a flower bed or veggie bed as a way of having lots of spring blooms to bring inside. Sale bags of tulips are a good bet for this, since you will be removing or lifting the bulbs after they bloom.

Bulbs can be included as part of a cutting garden as well. Consider using a portion of a flower bed or veggie bed as a way of having lots of spring blooms to bring inside. Sale bags of tulips are a good bet for this, since you will be removing or lifting the bulbs after they bloom.

Crocuses

Crocuses  Daffodils are a great group of bulbs to begin with. They come in a range of colors from the bright cheery yellow we all know, to soft pinks, stripes, vibrant oranges, greens, and brilliant whites. Large outward facing blossoms are a standard but there are small clusters with contrasting petals and double blossoms as well. In choosing plants think about what other shapes and textures will be a part of the garden. Finding a mix of colors, blossom forms and heights will allow you to mimic other plants in your design and compliment hardscapes. Daffodils will also naturalize well especially in partly shady areas.

Daffodils are a great group of bulbs to begin with. They come in a range of colors from the bright cheery yellow we all know, to soft pinks, stripes, vibrant oranges, greens, and brilliant whites. Large outward facing blossoms are a standard but there are small clusters with contrasting petals and double blossoms as well. In choosing plants think about what other shapes and textures will be a part of the garden. Finding a mix of colors, blossom forms and heights will allow you to mimic other plants in your design and compliment hardscapes. Daffodils will also naturalize well especially in partly shady areas. Tulips

Tulips

Mock orange shrub (Philadelphus virginalis): This late-blooming deciduous plant provides a stunning citrus fragrance and can be used in groups as screening or as a stand-alone specimen. They also make excellent cut flowers indoors. It’s not a true orange, and its name supposedly derives from the fragrant white flowers which in some varieties resemble that of orange blossoms.

Mock orange shrub (Philadelphus virginalis): This late-blooming deciduous plant provides a stunning citrus fragrance and can be used in groups as screening or as a stand-alone specimen. They also make excellent cut flowers indoors. It’s not a true orange, and its name supposedly derives from the fragrant white flowers which in some varieties resemble that of orange blossoms. Phlox (Phlox paniculata): This native American wildflower is also known as garden phlox and summer phlox. They are sun-loving perennials with a long flowering season. Phlox are tall-eye-catching plants with large clusters of pink, lavender or white flowers, called panicles. They bloom for several weeks in summer and make excellent cut flowers.

Phlox (Phlox paniculata): This native American wildflower is also known as garden phlox and summer phlox. They are sun-loving perennials with a long flowering season. Phlox are tall-eye-catching plants with large clusters of pink, lavender or white flowers, called panicles. They bloom for several weeks in summer and make excellent cut flowers. Goldenrods (Solidago spp.): A native to the United States,

Goldenrods (Solidago spp.): A native to the United States,